The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

The list kept growing.

First, it was saxophonist Marcelo Peralta, who turned 59 just days before he died after contracting the coronavirus on March 10 in Madrid.

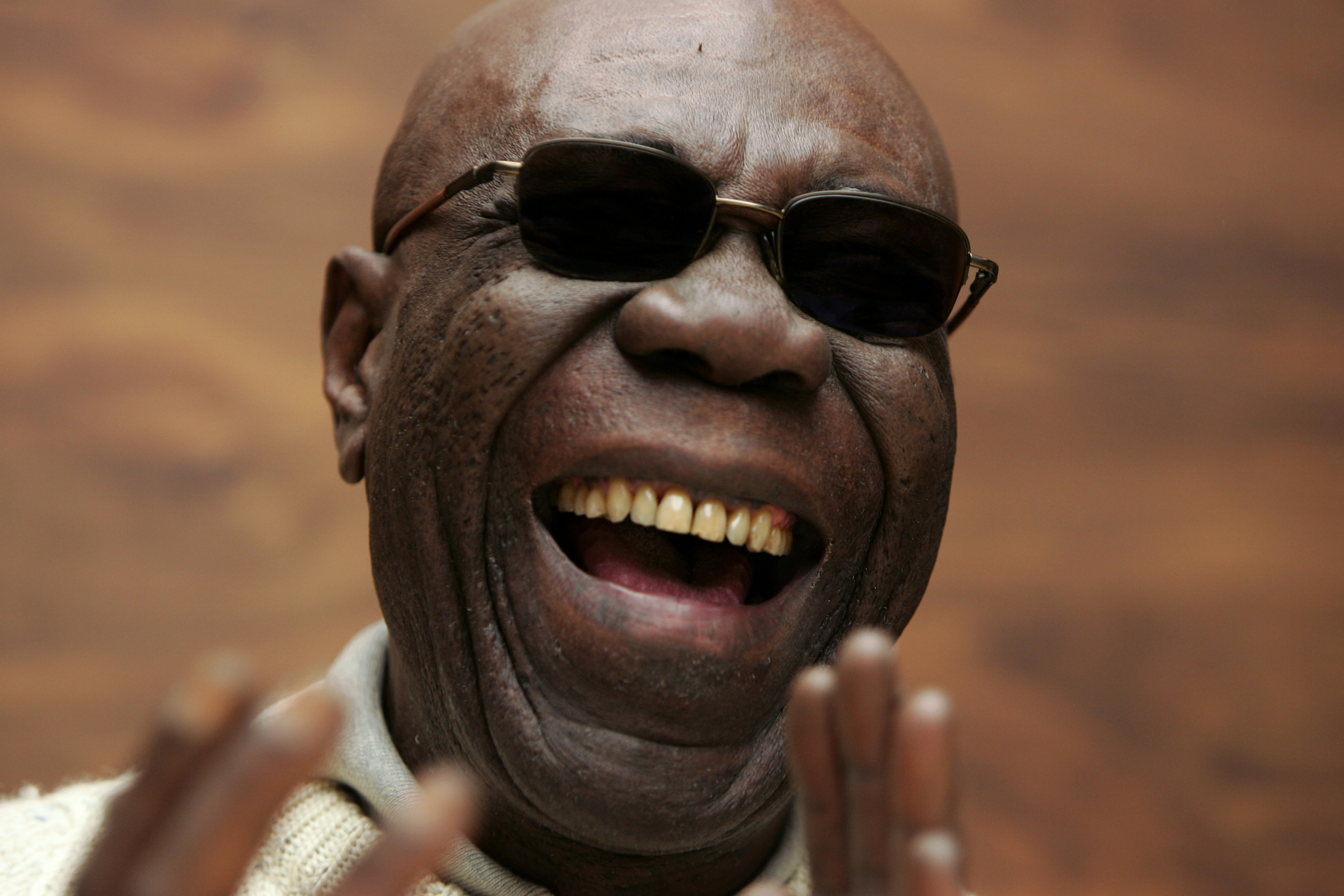

Then it was Manu Dibango, 86, a Cameroonian afro-jazz saxophone icon.

Then Mike Longo, 83, a pianist and musical director for Dizzy Gillespie.

Then revered trumpeter Wallace Roney, 59.

Then, on April 1, two deep blows: 85-year-old Ellis Marsalis Jr., a pianist, educator, and patriarch of an illustrious jazz family, and jazz guitarist Bucky Pizzarelli, 94, whose acclaimed work crossed genres.

The sudden and ongoing string of deaths of legendary jazz musicians from COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, has devastated the sprawling but close-knit community around the world.

"This has really been a bad few days," Arturo O'Farrill, a Grammy-winning pianist and founder of the Afro Latin Jazz Academy of Music, told BuzzFeed News.

"It was really difficult," he said, to learn that a number of musicians he knew and played with had fallen to the virus.

"It’s unbelievable to me — so many people. Day after day, it's someone else new," Waldron Ricks, a trumpet player in New York City who learned under Roney and played with Longo, told BuzzFeed News.

Ricks, now 52, took trumpet lessons with Roney when he moved from Detroit to New York City as a teenager. Roney was a deeply inspiring musician, Ricks said — and a "very strict" teacher.

"He would make sure you do it right or you'd be repeating the lesson...No slack. No messing around," Ricks said. "Wallace pretty much exposed me to what the possibilities were as a jazz musician. He kept talking about how it was an honor to be a jazz musician...Not just a musician, but a jazz musician."

Roney, who was Miles Davis's protégé, died of complications from COVID-19 in Paterson, New Jersey on Tuesday morning.

With the number of confirmed coronavirus cases in the US nearing a quarter of a million and the death toll surpassing 6,000 as of Friday morning, officials continue to scramble to contain the spread of the disease. That giants in the jazz world are falling to the coronavirus, bassist Christian McBride said, "is proving that everybody can be touched by this. Everybody is eligible."

"I have to worry that this very well may hit more musicians, but particularly elderly musicians," he told BuzzFeed News.

McBride, a six-time Grammy winner whose European tour with pianist Chick Corea was canceled due to the pandemic, said he's checking in with as many musicians as he can, especially the older ones.

"I certainly have tried to keep a closer eye on the elders," he said. "Our treasures, like Roy Hanes who’s in his nineties, Lou Donaldson, and George Wein and Lee Konitz and Chick Corea. Wayne Shorter. Sonny Rollins. We gotta bubble-wrap them cats."

Like service and gig workers, musicians are facing an unprecedented battle to survive as events are postponed indefinitely and nonessential businesses remain closed for the foreseeable future. In the past week, a stunning 6.6. million people in the US have filed for unemployment benefits.

"Being a jazz musician means you’re self-employed," McBride said. "And a lot of self-employed people out there who have lost a lot of income, they’re sitting at home with no work. They’re trying to figure out how to make it."

The lucky ones among them have savings or "have set themselves up in some way or another for later in their life," Antonio Sanchez, a jazz drummer, told BuzzFeed News. But not everyone can or does do that.

Ricks said getting health insurance "was a big deal" for him — it was one of the reasons he went into teaching.

For Sanchez, one of his concerns is how long it will take for people to feel safe being out in a large crowd again.

"When are people going to feel comfortable again to travel freely like we do in order to work? And then for a bunch of people to get together in one place, very close together, to listen to music?" Sanchez said. "That’s going to take a long time. Understandably so."

Though jazz musicians live and perform around the world, the community is nonetheless an intimate one. Sanchez, whose work on the Birdman soundtrack earned him a Grammy, said he often ran into Longo and Roney in the festival circuit.

"We saw each other a million times at different jazz festivals and stuff. It’s a very small community," he said. "That’s why even though you don't necessarily have to have direct interaction with them, it just feels very close to home."

As a longtime sideman in NYC, Ricks had a more personal relationship with Longo, a renowned pianist who worked alongside Gillespie, "the ambassador of jazz," for years.

"Mike was funny," Ricks, who played with Longo's big band, recalled. "He always had a joke, always had an anecdote."

Even when the band wasn't playing at its tightest, Longo found ways to motivate them. "We'd end up playing the music better because we wanted to play it for him," Ricks said. "We were all heavily invested because Mike made us feel that way."

The news that both Marsalis and Pizzarelli had died on Wednesday plunged a community already hurting from the spate of deaths among their elders into deeper mourning. To see this many older musicians — "the creators of what we do," Sanchez said — die from COVID-19 has been disheartening.

"It’s very scary to see some of these people go," he added. "Because that’s our last connection to that. To the beginnings of our music."

O'Farrill said hearing the news about Pizzarelli and Marsalis, who were instrumental in shaping his work, "was a little bit like watching a beloved uncle or father or mother die."

They were both as beloved by the community as they were successful, O'Farrill recalled.

"They were such nice people too... They were examples to me of humanity and gentleness and generosity," he said. "I feel like we lost more than musicians and icons. We lost a high bar for one should behave as a human being."

On top of their exalted statuses in the jazz world, Marsalis and Pizzarelli were fathers to acclaimed musicians in their own right.

Pizzarelli's son, John, is a well-known jazz guitarist like him. Marsalis, along with his sons Brandon, Wynton, Delfeayo, and Jason Marsalis, are hailed as the "first family of jazz."

"You could really sense from talking to Ellis or Bucky where their sons got so much information, so much of their mannerisms, and so much of their abilities and their grace," O'Farrill said.

On Thursday, Wynton posted a moving tribute to his dad on Facebook.

"Ironically, when we spoke just five or six days ago about this precarious moment in the world and the many warnings he received ‘to be careful, because it wasn’t his time to pass from COVID’, he told me, 'Man, I don’t determine the time. A lot of people are losing loved ones. Yours will be no more painful or significant than anybody else’s,'" he wrote.

"In that conversation, we didn’t know that we were prophesying," he went on. "But he went out soon after as he lived — without complaint or complication."

CORRECTION

Jason Marsalis was misidentified in a photo caption in an earlier version of this post.