Just as we were all looking forward to the holiday season, hoping to put the Delta coronavirus wave behind us, the World Health Organization sounded a fresh alarm on Nov. 26 about the Omicron variant. Announced by South African scientists just two days before, the WHO designated Omicron as an official “variant of concern” because it seems to be spreading quickly and may possess mutations that could help evade vaccines or immunity from prior infections.

The first case of COVID-19 caused by the Omicron variant in the U.S. was confirmed in San Francisco on Dec. 1, in a fully vaccinated person who had recently traveled to South Africa.

When Delta began to threaten the US in early June, it had already caused a devastating COVID wave in India and gotten a strong foothold in the UK. With South Africa having alerted the world so quickly, scientists are still struggling to work out how dangerous this new variant might be.

While we wait on that data, here are some key questions and what we know so far:

How transmissible is Omicron compared to earlier variants?

Omicron was first identified in South Africa and Botswana in November, and coincided with a rapid uptick in cases, especially in the Gauteng Province in South Africa’s Highveld. “In recent weeks, infections have increased steeply,” the WHO noted.

That led to a flurry of genomic sequencing of viruses from patients in Gauteng. The extra volume of sequencing could make the virus seem to be spreading more quickly than it really is, Trevor Bedford of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, a specialist in viral evolution, noted on Twitter.

What scientists now need to work out is whether Omicron is sufficiently transmissible to replace the currently dominant Delta coronavirus variant, which emerged in India in late 2020. From June 2021 in the US and in Europe, Delta quickly replaced the Alpha and Beta variants, first identified in the UK and South Africa respectively. Its high transmissibility is also believed to have prevented the Lambda variant, first identified in Peru in the summer of 2020 and once a big concern because it seemed to have some resistance to vaccines, from taking hold across the globe.

It may take several weeks to work out how quickly Omicron spreads compared to Delta. “Omicron will turn out either to be Beta-like, and vanish, or a super-Delta, and a problem,” John Moore, a virologist at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, told BuzzFeed News by email. “Time will tell.”

Is it more or less deadly than earlier variants?

Amid scary headlines about the Omicron variant, one initial hopeful sign came soon after the WHO's announcement, when Angelique Coetzee, a doctor in Pretoria who treated some of the first patients carrying the variant, told the UK’s Telegraph newspaper that they had relatively mild disease. “Their symptoms were so different and so mild from those I had treated before,” said Coetzee, who chairs the South African Medical Association.

But other experts say it’s too early to tell whether Omicron is more or less deadly than earlier variants. On Nov. 28, Francois Balloux, director of the University College London Genetics Institute, tweeted: “The omicron variant could be less, as much, or more transmissible and/or virulent than prior SARSCoV2 lineages in circulation. Only real data will tell, and any prediction about omicron's virulence remains largely futile at this stage.”

Answering this question means looking at rates of hospitalization and deaths among patients with the Omicron variant — controlling carefully for their age, which is a huge factor in how hard the coronavirus hits.

“It should take a couple of weeks to have reasonably solid data on hospitalization rates,” Balloux told BuzzFeed News by email. “For mortality rates we will have to wait for a bit longer. The first good evidence should come out of South Africa as they have reported the highest number of cases to date.”

Why are scientists concerned about Omicron?

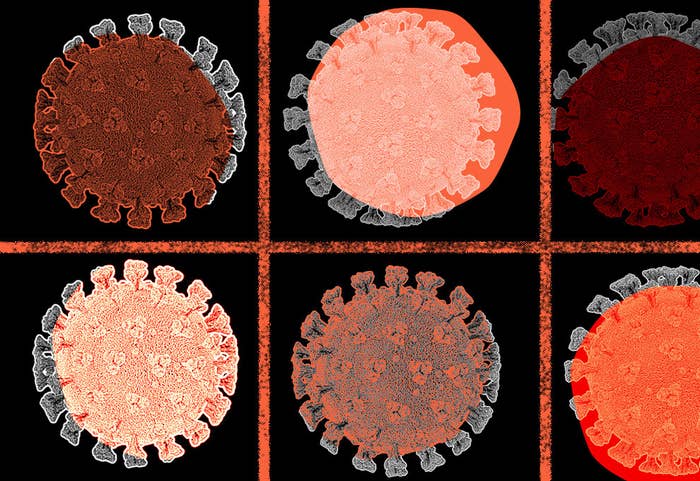

Omicron has at least 30 mutations in the spike protein that the coronavirus uses to enter human cells, 15 of which are in the part of the protein that actually binds to its target receptor. Worryingly, some of these mutations are known from earlier variants to make the coronavirus more transmissible. One, seen in the Alpha, Beta, and Gamma variants, improves the ability of the virus to bind to its receptor. Other mutations may help the coronavirus evade antibodies. But Omicron also contains novel mutations whose effects are not yet known, so predicting how it will behave is difficult.

In its Nov. 26 statement, the WHO pointed not only to the rapid rise of Omicron in South Africa, but also the fact that it seems more likely than other variants to infect people who have previously had a case of COVID. “Preliminary evidence suggests an increased risk of reinfection with this variant,” the WHO said.

How should I change my behavior?

As with previous variants including Delta, all the usual measures we can take to reduce viral transmission will help reduce the spread of Omicron. The WHO’s Nov. 26 statement said: “Individuals are reminded to take measures to reduce their risk of COVID-19, including proven public health and social measures such as wearing well-fitting masks, hand hygiene, physical distancing, improving ventilation of indoor spaces, avoiding crowded spaces, and getting vaccinated.”

Bob Wachter, chair of UCSF’s School of Medicine, stressed the same advice in a tweet:

What to do now? 1) If not vaxxed, get vaxxed 2) If not boosted & >4-5 mths out, get boosted 3) Get prepared mentally to act more cautiously if Omicron proves to be more infectious, immune-evasive, or both 4) Follow the news & science – will be much clearer in 2-3 wks 5) That's it

In the US, successive waves of COVID have turned around and started to subside after about two months of steady growth. This often seems to happen when people see news reports of local hospitals becoming overwhelmed by seriously ill people.

“It’s right around that point that we note that behavior rapidly changes and the surge subsides,” Spencer Fox, associate director of the University of Texas COVID-19 Modeling Consortium, told BuzzFeed News last week, before news about Omicron broke.

The challenge now is to convince people to modify their behavior before things have gotten out of control. Unfortunately, the emergence of Omicron comes just as cases in the US were already starting to tick up again after the decline of the first Delta wave.

In a press briefing on Nov.29, President Joe Biden encouraged Americans to get vaccinated or get a booster shot if they haven’t yet done so. He also urged people to “please wear your mask when you’re indoors, in public settings, around other people,” but indicated that no new mask mandates and lockdown restrictions are planned at this time.

Should I cancel holiday travel plans?

Current CDC recommendations are to delay travel unless you are vaccinated. Factors to consider in weighing whether to travel include the transmission rate where you are headed, and where you will travel through. “If you and your family are fully vaccinated, you can celebrate the holidays much more safely,” Biden said.

Some data on whether the Omicron variant is more contagious or severe than Delta could emerge by the middle of December, which might affect your plans.

Experts mostly continue to recommend the same precautions as they did before the Omicron news. If you are flying, vaccination, boosters, and mask-wearing are the three most important things you can do, said Reynold A. Panettieri Jr., vice chancellor for Translational Medicine and Science at Rutgers University.

“I would undoubtedly use a mask and practice social distancing and hand-washing on the plane or in the airport,” he said. “I certainly would not lower my guard at this point, we just don’t know about the variant.”

As for holiday parties, Panettieri recommends that you weigh the risks and take into consideration the attendees’ vaccination status.

“Parties tend to be loud, there tends to be dancing and shouting and celebration,” all of which can spread viruses, he said. “I think you have to be cautious.”

Smaller parties where you know all the individuals and can practice social distancing and hand washing are “probably going to be fine,” Panettieri said.

Will international travel bans make any difference?

Starting Nov.29, the US restricted travel from South Africa and seven other countries in the region — although citizens and permanent residents are still allowed to return to the country. But it’s highly unlikely that this will keep Omicron from spreading in the US. The first US case was confirmed Dec. 1 and the variant was previously detected in countries including Belgium, Germany, Italy, Australia, and the UK.

“Travel bans can buy time if you’re in front of a virus, but I don’t think we’re in front of it,” Ingrid Katz of the Harvard Global Health Institute told BuzzFeed News over the weekend.

Some experts think that travel bans are futile and are sending a dangerous message by effectively punishing the countries that raised the global health alarm. At best, they may provide a little more time to prepare for an Omicron surge. The UK, for instance, was hit earlier by the Delta variant than most other European countries, likely because of large numbers of people traveling from India during the height of its Delta wave. Prime Minister Boris Johnson was heavily criticized by opposition politicians for not imposing restrictions on travel from India more quickly.

Biden acknowledged the limits of travel bans in his press conference on Nov.29. “The point of the restriction [is] to give us time to get people to get protection, to be vaccinated and get the booster,” he said.

Will existing vaccines work against Omicron?

Experts don’t expect Omicron to completely evade our current vaccines. The big question is whether its spike protein contains enough important changes from earlier variants that antibodies generated by the shots distributed so far will be less effective at neutralizing the virus.

To answer this question, scientists will first conduct lab tests to see whether the Omicron variant is able to partially evade neutralizing antibodies. “It will take 1 to 2 weeks to generate lab-based data on the antibody-resistance properties of the omicron spike,” Moore told BuzzFeed News by email.

On Nov. 26, Moderna announced that it is testing three existing vaccine booster candidates against Omicron. Two of these were designed to work against multiple variants and contain mutations from the Beta and Delta variants that are also present in Omicron.

If they don’t work well, how quickly could a vaccine against Omicron be made?

One advantage of mRNA vaccines like the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna shots is that they can be redesigned and put into mass production far more quickly than older vaccines. BioNTech has said that it could produce and start shipping an Omicron-specific vaccine within 100 days, if necessary. In a statement to investors, Moderna suggested a variant-specific vaccine could be ready by early 2022.

Johnson & Johnson, the maker of the other US-authorized vaccine, said on Nov.26 that it is also working on a variant-specific vaccine. The company is right now testing blood serum from its booster study participants to measure vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron variant. Its vaccine is a modified version of a harmless cold virus engineered to alert the immune system to coronavirus spike proteins, which would take longer to customize for a specific variant.

Should I get vaccinated and get a booster? Or wait for an Omicron-specific shot?

Get vaccinated and get a booster, public health experts are advising, rather than waiting for a variant-specific shot. That’s because existing vaccines will still provide some protection against infection and even more against severe disease. A vaccine creates antibodies that should still target some of the unmutated parts of the spike protein on the variant. A booster creates 5 times more antibodies than a two-dose vaccine does, and 50 times more than infection by the virus, according to a recent study.

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky on Nov. 29 updated the agency’s booster recommendations to state that everyone 18 and older “should” get a booster, citing concerns about the Omicron variant.

How well will antiviral COVID-19 therapies work against Omicron?

Oral antiviral drugs from Merck and Pfizer — which appear to be very effective at treating COVID-19 — are expected to work well against disease caused by the Omicron variant. The medications (both of which could receive emergency use authorization from the FDA in the next few weeks) target viral replication, which is less affected by the mutations found in Omicron. One Merck study earlier found its antiviral drug, molnupiravir, was equally effective against several earlier variants, although research on its specific effectiveness against Omicron is ongoing.

However, this doesn’t mean antivirals can fully blunt the Omicron threat. On Nov.26, Merck reported that its antiviral pill may be significantly less effective than it initially appeared. In its final analysis ahead of an FDA review, the company reported a 30% reduction in hospitalizations and death among high-risk patients, much lower than the 50% reported in early estimates.

Vaccines remain the preferred tool to fight COVID-19 because they can prevent infections and reduce spread — minimizing the opportunity for the virus to mutate further.

Where did this new variant come from?

Although the first confirmed COVID cases caused by the Omicron variant were detected from South Africa and Botswana — the earliest sample was collected on Nov. 9, according to WHO — that doesn’t necessarily mean that the virus emerged in either of those countries. Indeed, Omicron’s mutations indicate that it may have diverged from other variants more than a year ago, Bedford noted on Twitter. If so, it could have been circulating for months under the radar somewhere without good surveillance for new variants — likely elsewhere in Africa.

Another possibility is that the virus acquired its mutations while chronically infecting someone with a compromised immune system, which has been documented in the past. The high prevalence of HIV across Africa means that there would have been many opportunities for this to happen. “The two scenarios are not mutually incompatible,” Balloux told BuzzFeed News by email.

Uncertainty around the origins of Omicron provides another reason why selective travel bans aimed at countries in southern Africa may be ineffective.

Why is it called Omicron?

In May this year, WHO started naming variants after Greek letters, to be less confusing than scientific designations, which involve combinations of letters and numbers — so B.1.617.2 became Delta. This variant was expected to be called Nu, the next letter in the Greek alphabet, but WHO avoided that name because of the potential for confusion with “new.” WHO also skipped Xi. Even though the Greek letter is pronounced differently, this wasn’t used because Xi is the transliteration of a common Chinese name, a WHO official told the New York Times. (It is also the name of China’s president.) Omicron was next on the list.

This is a developing story. Check back for updates and follow BuzzFeed News on Twitter.