You might have heard the saying that life is 10% what happens to you and 90% how you react to it. If that saying were a person — well, have you met Rachel Hollis? Hollis, now a successful blogger, speaker, and author of the mega-best-selling book Girl, Wash Your Face, has come a long way from where she started: the tiny town of Weedpatch, California, an unincorporated community southeast of Bakersfield that’s one of the poorest parts of Kern County, with 2,394 residents and a median household income of $28,451.

You might remember that name from a scene in The Grapes of Wrath, in which a watchman at the migrant worker camp in Weedpatch tells the Joad family about the “Holy Rollers” — Pentecostal ministers — who had been coming through town. They kept asking for money, so the camp’s Central Committee decided that “‘Any preacher can preach in this camp. Nobody can take up a collection in this camp.’ And it was kinda sad for the old folks, ’cause there hasn’t been a preacher in since.’”

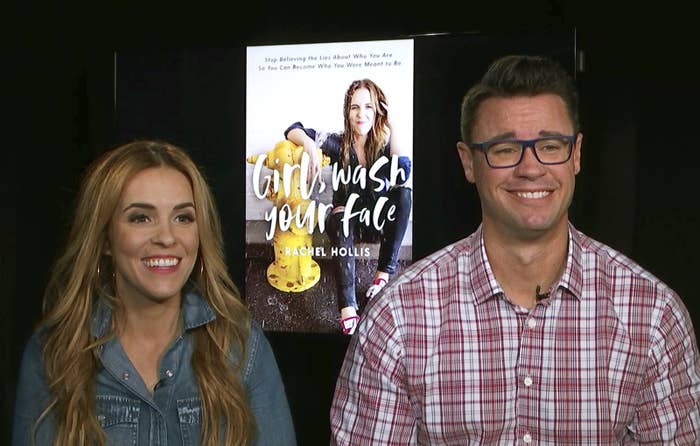

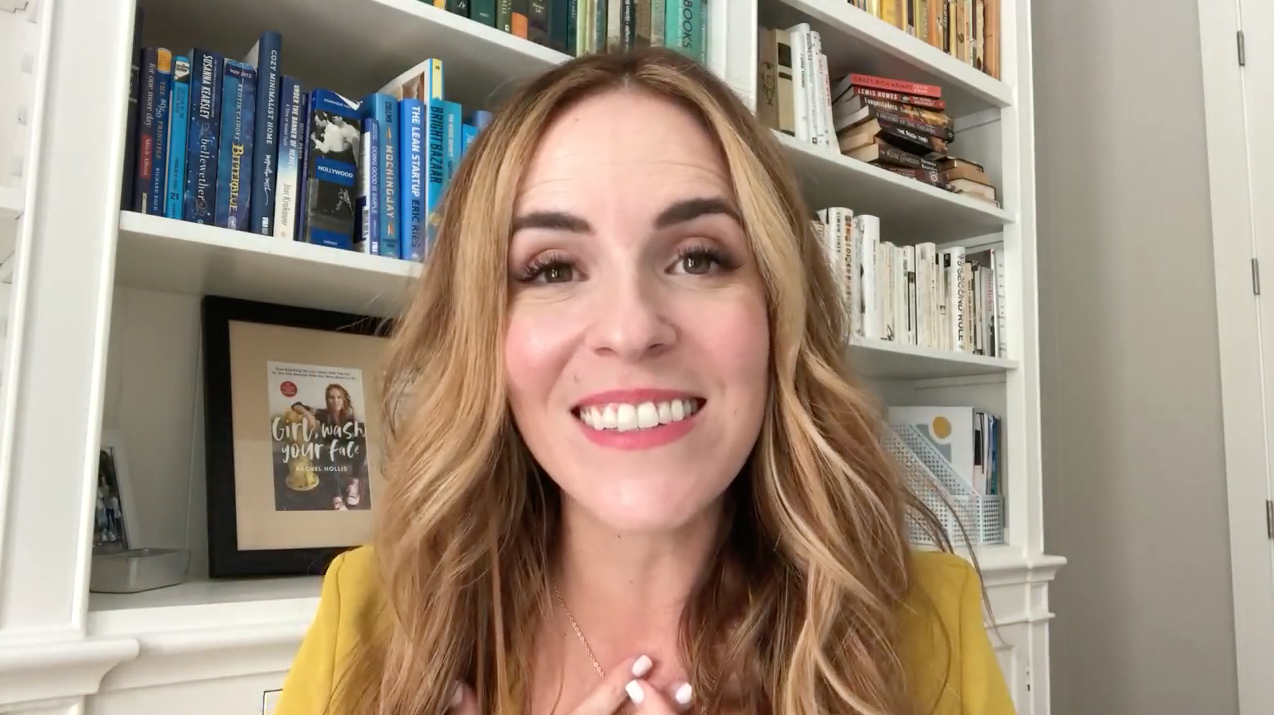

Hollis is herself the daughter and granddaughter of Holy Rollers whose family migrated from Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Kansas to end up in Weedpatch. She writes in the book about leaving home after high school and striking out for Los Angeles, where an obsession with Matt Damon led her to apply for (and get) a job at Miramax (which had produced Good Will Hunting). That job led to Rachel meeting her husband and eventually starting a wildly successful event-planning company, Chic Events, which morphed into a lifestyle blog called the Chic Site, which in turn has led to the creation of a nebulous, evolving business empire — first the communications and branding company Chic Media, now the Hollis Company, through which Hollis and her husband Dave (now the company’s CEO) oversee her motivational speaking circuit and podcast as well as “Rise” conferences for women and couples. And did I mention the books? At 35, now living outside of Austin, Hollis has written three novels, two cookbooks, and, as of this year, the #1 New York Times best-selling book Girl, Wash Your Face.

Girl, Wash Your Face, which was published in February 2018 by Thomas Nelson, a HarperCollins imprint devoted to “Christian content,” is an amalgam of stories, tough-love advice from a woman who has been there, and vaguely biblical encouragement. This is structured by tackling the various “lies” that Hollis believes have held her back — and maybe you too? — which she deconstructs chapter by chapter: “I Am Bad at Sex,” “I Should Be Further Along by Now,” “I Am Defined by My Weight,” and so on. “Recognizing the lies we’ve come to accept about ourselves is the key to growing into a better version of ourselves,” Hollis writes.

Promotional copy from the publisher’s website describes it thusly: “With unflinching faith and rock-hard tenacity, Girl, Wash Your Face shows you how to live with passion and hustle — and how to give yourself grace without giving up.” It’s simple, according to Hollis: Stop breaking promises to yourself. You, after all, are the only one in control of how your life goes.

It is hard to overstate the popularity of this book. Since its release in February, according to Publishers Weekly, Girl, Wash Your Face has maintained a spot in the top 10 best-selling books in the country for seven months, has held the No. 1 spot for 12 of those weeks (it is now No. 8), and has sold more than 880,000 total copies in the US. The book has almost 7,000 Amazon reviews, the vast majority of them five stars; as of the week of Nov. 4, it remains the No. 1 best-selling nonfiction book on Amazon, and currently the site’s second-most popular book of the year (outsold only by Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury). But if you aren’t already familiar with the book, or Hollis, you might be forgiven for wondering: What, exactly, is she saying that people are so eager to hear?

The internet has given rise in the last few years to a phenomenon I’ve come to call “curated imperfection,” and Hollis is one of its reigning doyens. To her Instagram following of more than 825,000, Hollis regularly posts inspirational quotes from her own writing (“You were not made to be small”), selfies in which she is not looking at the camera but is holding her book up to the camera, and photos with her husband reminding you to subscribe to her podcast or check out their marriage conference (which she calls a “getaway weekend” and cost $1,795 per couple for two days in September, hotel not included, no refunds).

Hollis is all of us — only she doesn’t have to try at all. Or is she trying the hardest?

Hollis also uploads a steady trickle of videos to her 71,000+ YouTube subscribers, with topics ranging from chatty family life updates (“Say Hello to Dave’s New Bronco!”) to, recently, inspirational montages pieced together from her speaking engagements (“Do you feel like giving up?”). The homepage of the Chic Site, as of mid-October, featured a recipe for slow-cooker pumpkin spice latté, a post about how to incorporate Spanx leggings into your fall look, and a video on how to host a “Girls Night In,” sponsored by Rubbermaid.

Even as the core of Hollis's business shifts away from being, as she puts it, “a lifestyle influencer,” this lifestyle is still largely what Hollis is selling. She wants to be relatable, and she is, to many thousands of women, in her blog posts and her speeches and her best-selling book. “I’m not an expert. I’m not a guru,” Hollis told the AP in September. “Anything I’ve ever done, the work I’ve done, has always been like your girlfriend telling you what worked for her.” Hollis is all of us — overloaded, exhausted, smiling through the long days of work, child care, meal prep, and relationship highs and lows. Only she doesn’t have to try at all. Or is she trying the hardest?

Hollis “vowed to be authentic and sincere” in her online life, which is why, she writes, “for every gloriously styled cupcake picture we produced, I shared a photo of myself with facial paralysis.” (She at one point suffered from stress-related Bell’s palsy.) In the book’s first chapter, Hollis describes getting dressed up and attending the Oscars with her then-Disney executive husband. “In these instances, photos show up on Instagram and Facebook of us looking well coiffed and ultra glam, and the internet goes wild.”

Note the use of the passive voice here: “photos show up.” Not “photos are strategically posted at just the right time of day by my social media team for maximum engagement.” But even the “messy” pictures of Hollis are adorable, so maybe it doesn’t matter whether she’s wearing sweatpants or a designer brand so much as that her audience believes it’s real. Authentic. Sincere. Is that dishonest? What is honesty when your life is your brand?

Hollis’s vow of authenticity doesn’t seem to extend very far into difficult political conversations, which isn’t surprising for someone with a popular lifestyle brand to maintain. In one YouTube video from August 2016, she referenced the “terrifying” state of politics in the US — just before saying, “I’m not going to talk about my beliefs or my political affiliation, because I know that we’re gonna some of us disagree, and I’d rather not know if you disagree.”

But to my mind, her core philosophy itself is emblematic of a huge division in American thought that dominates our national discourse: Are people who have problems responsible for fixing them themselves? Or is there some collective responsibility that we are shirking — does a society owe something to all its members? There are dark implications in making everything a matter of personal responsibility, which is Hollis’s bias. She asks us to interrogate and deconstruct the lies that we’ve believed about ourselves, and I wonder how that lens would function if we turn it on the lies she promulgates in Girl, Wash Your Face.

There are dark implications in making everything a matter of personal responsibility.

The lie: “You, and only you, are ultimately responsible for who you become and how happy you are.”

In good faith, I think that what Hollis (who declined to be interviewed for this story) means here is some “I am the captain of my soul,” “Invictus” stuff: I have to make the decision to be happy; no one else is going to do that for me. And to a degree, that makes sense. Your mental, physical, and emotional well-being are influenced by your mindset. But mindset isn’t the only thing that influences your well-being.

Not everyone has enough money to let them take the kind of professional and financial risks that might lead to greater happiness, for example. Things like systemic racism can wear on a person to the point that it degrades her health at the same time it restricts her access to good health care, resulting in higher rates of chronic disease and shorter life expectancies for black women than white women.

Can you tell a woman who has lost her hoped-for child as a result of state officials turning a blind eye to a water-poisoning crisis in a predominantly black area, or a mother seeking asylum whose child was taken away from her at the border, that “you are ultimately responsible for who you become and how happy you are”? You can, but you would be wrong. And cruel. Hollis doesn’t address the possibility that for some people, obstacles to happiness are outside their control. And it is proof of her hard-earned privilege that she doesn’t have to.

In a recent Instagram post thanking her followers for helping her sell over 1 million total copies of Girl, Wash Your Face, Hollis gives us some insight into whom she considers to be her target demographic, and who makes up the small army of readers that has helped build word-of-mouth buzz for her book: “Thank you for writing a review! Thank you for hollering at the other girls on your MLM team to read it! Thank you for telling the other wives on base that it’s worth their time!”

I spoke with more than a dozen women for this story — friends of friends, people who responded on social media, and at least two women I spotted out in the wild — to try to understand exactly what it is about Hollis’s gospel that appeals to them.

“I think the adversity she’s been through gives her a lot of credibility,” said Alex Ethridge, a 27-year-old marketing professional in Missouri. (Hollis had a difficult family upbringing — she calls it “traumatic” — and was just 14 years old when she found her older brother, Ryan, after he had killed himself.) Elissa Johnson, a 35-year-old mom in St. Louis who co-owns a small business with her husband, told me she appreciates Hollis’s tough-love approach: “There’s something refreshing in a post-truth world about rooting out some lies you might be telling yourself … It feels like so many things are out of our control in the world today, but there’s so much within our reach.”

One of Hollis’s videos was particularly helpful for Chrissy Malson. A student and part-time teacher’s aide near Peoria, Illinois, Malson told me she always put herself “last on the list” and put her career on hold for her husband’s. She decided to go back to college last year to get a degree in occupational therapy. “This is terrifying for me,” Malson said. “Going back to college is scary.” But watching Hollis’s video about taking control of her life has inspired Malson. “It’s a reminder that ... I can do hard things. I can do things that scare me. Yes, I have a family, a special needs kiddo, a husband who travels internationally, but I can do this. I define my reality.”

The video includes an image of Hollis running through a crowded room, high-fiving the people who have gathered to hear her speak. “You get to decide, right now, who you want to be,” the voiceover says. There is something to this, and something to hearing it from a woman, at least in a way that trades on a certain kind of privilege. I do get to decide, I want to tell myself. And I can decide. I am writing this on the outdoor patio of the $250/month coworking space I belong to in San Francisco, one of the most expensive cities in the world, where, thanks to my husband’s salary from his tech-sector job, I can afford to live.

Being empowered to let go of my anxiety or self-criticism as a wealthy white woman is certainly helpful to me, and I appreciate that message from Hollis on a certain level. But my anxiety is largely rooted in unrealistic fears, whereas many women don’t have the opportunity to go back to college or own a house from which to be liberated. Hollis’s book is in many ways a return to the kind of second-wave feminism that privileged the liberation of middle-class straight white women from the domestic sphere while at the same time completely ignoring — or actively opposing — the rights and needs of poor and queer and nonwhite women.

Hollis, who has four children, doesn’t mention child care at all in the book until the acknowledgments, when she thanks her nanny: “People ask me how I do it all, and the honest truth is, I absolutely don’t,” she writes. “Behind the scenes is an incredible, loving friend and sister who takes care of my kiddos when work or travel takes me away from them.”

In one anecdote about the power of setting goals, Hollis recounts her obsession with buying a Louis Vuitton Speedy bag, which cost a thousand dollars. “I wanted it because it represented the kind of woman I dreamed of becoming,” she wrote. The day she got her first $10,000 consulting check, Hollis drove to the Louis Vuitton store at the Beverly Center and walked out with her bag.

Hollis makes no attempt to interrogate her desire for an expensive designer bag here, just as there is no effort to interrogate her desire to own a vacation home in Hawaii by the time she’s 40. “Honestly, I think it’s kinda shameful and not something to be proud of," said Amber Cessac, a 32-year-old mother of five in Austin. The book caught Cessac’s eye at a local Target, and she found a few “nuggets of inspiration” in it. But she was turned off by what she saw as Hollis’s constant push for bigger and more expensive things. “She just comes off as so incredibly tone-deaf,” Cessac said.

Hollis equates having “made it” with being able to drop a lot of cash on a status-symbol bag, using purchasing power as a path to self-realization.

There is more than a hint of #Girlboss corporate feminism at work here, as Hollis equates having “made it” with being able to drop a lot of cash on a status-symbol bag, using purchasing power as a path to self-realization. And she takes that brand of feminism a step further by marrying it with Christianity, in what is essentially a Pinterest-worthy version of the prosperity gospel.

This attitude has a historical context in the Pentecostal religious tradition in which Hollis was raised. Pentecostalism has always been the slightly embarrassing uncle at the evangelical family reunion — its unfiltered and emotional expressions of faith can make it look a little unseemly to outsiders. And Pentecostals have long associated spiritual blessing with material wealth, which may help explain why there is something talismanic about the Louis Vuitton bag for Hollis: It showed that her hard work and strategic goal-setting channeled the kind of earnest faith that God rewarded in the form of $10,000 consulting checks.

A patina of racial diversity has been another hallmark of Pentecostalism, although during the civil rights era, racism from white leaders of the church caused a division that lasted through the 1960s, and well into today in some parts of the country. In the United States, the movement gained momentum in the early days of the 20th century with several well-known revivals, the most famous of which was the Azusa Street Revival in 1906, led by a black preacher named William Seymour. And as far back as the Azusa Street Revival, white Pentecostals displayed a religious version of black cultural appropriation. Charles Fox Parham, a preacher and early proponent of Pentecostalism, heard reports that “white people [were] imitating the unintelligent, crude negroisms of the Southland, and laying it on the Holy Ghost.”

Interestingly, this kind of appropriation echoes throughout Girl, Wash Your Face. It is impossible to read the book and not notice Hollis’s frequent use of African American Vernacular English, beginning with the title. The book’s introduction is called “Hey Girl, Hey,” and Hollis uses a popular mangled version of a Maya Angelou quote (“when you know better, you do better”) to explain why she wants to become a better hip-hop dancer.

Osheta Moore started following Rachel Hollis when Moore was living in Los Angeles. “I was going through this season of isolation after a cross-country move, and I wanted some inspiration,” said Moore, a pastor and author. “There was a time when she was more open about some of her family struggles and things that were going on, and I just found that really refreshing.” Moore was so inspired by Hollis’s work that she ended up getting an internship at Chic Media for several months in 2016, just before she published her own book. After working at Chic and following Hollis more closely, Moore started to notice that Hollis was influenced by “prosperity teachings” and people like Tony Robbins.

When Moore, who is black, interned at Chic, she said “it was a very diverse workspace.” She felt that Hollis had a blind spot around race, but liked the diversity of the team she worked with. There came a time, though, when Moore — as a woman who at one time hoped to work her way down to a size 14, a size Hollis said she was when she was her highest weight ever — “realized that either I had to kind of adjust some of my expectations in order to continue working there or change some of my views about my own body.”

“For me, the point where it became really dangerous was when I noticed a fat-shaming component to her platform,” Moore said. “There’s a lot of talking about how being overweight is hindering you from achieving your dreams, or, ‘If you don’t stick to your diet, then you’re not a person of integrity.’ That shaming component is really harmful.”

“You get one and only one chance to live, and life is passing you by,” Hollis writes in the introduction to Girl, Wash Your Face. “Stop beating yourself up, and dang it, stop letting others do it, too.” But anyone reading her book may find it hard to follow that last bit of advice. The trouble with, and the appeal of, curated imperfection is the assumption that all imperfections lie in the past — they have supposedly been understood, integrated, and learned from in order to create a present that is blissfully free from earlier mistakes. And at her worst, Hollis refashions her own (apparently resolved) struggles into astonishingly harsh instruction for other women, under the guise of women’s empowerment and tough love.

At her worst, Hollis refashions her own (apparently resolved) struggles into astonishingly harsh instruction for other women.

In a chapter of Girl, Wash Your Face about her “emotional eating” and desire to lose weight, Hollis warns the reader, “This is where I should tell you that I am worthy and loved as I am. This is absolutely true, but that’s not where I’m headed with this chapter.” For the next several pages, she continues to shame fat people: “Humans were not made to be out of shape and severely overweight. You can choose to continue to abuse your body because it’s all you know … You can choose to settle for a half-lived life because you don’t even know there’s another way … But please, please stop making excuses for the whys.”

Hollis spends a lot of time on body image in Girl, Wash Your Face, but perhaps nowhere is it as harmful and ignorant as when she is berating people who do not “keep their commitments,” especially when using the example of dieting. “[D]iets do not work,” Michael Hobbes wrote in a recent HuffPost article on harmful misperceptions around obesity among medical professionals as well as civilians. “Not just paleo or Atkins or Weight Watchers or Goop, but all diets. Since 1959, research has shown that 95 to 98 percent of attempts to lose weight fail and that two-thirds of dieters gain back more than they lost.”

Yet, according to Hollis, we shouldn’t respect women who don’t stick with their diets because we cannot rely on them to keep their word. She imbues fatness with the shame of moral failure and demeans women who struggle to — or do not want to — lose weight. This is perhaps the clearest encapsulation of the cruelty baked into Hollis’s philosophy. But it’s certainly not the only example.

Hollis and her husband went through a difficult time before adopting their daughter Noah, now about a year and a half old, in 2017. They signed up to be foster-to-adopt parents, and Hollis talks throughout the book about their wrenching experience with the adoption process. It was in the middle of these tumultuous few years, full of long days spent in survival mode, that Hollis started drinking more. “Vodka was my copilot, and I was grateful for its presence in my life,” she writes.

But she has little to no empathy for the birth parents or family of the children she and her husband thought they would permanently adopt. When Hollis recounts waiting for the birth parents of one child to show up, her attitude of superiority and willful ignorance is almost breathtaking:

How do you keep taking babies to see parents who aren’t parenting? How do you give up half a Saturday to wait in a McDonald’s playland for addicts who may or may not show up, then hand over an innocent baby and watch them erase whatever progress you’ve made with their daughter? How do you do all of this KNOWING that they’ll be reunited at the end of it all, and there’s nothing you can do about it? If you’re like me, you find a way. But at night, when no one is looking, you drink, and when it gets really bad, you take a Xanax, too.

Hollis has made no secret of her past drinking issues; in an interview in September, she said, “I was abusing alcohol. I was making really poor choices, and I thought, gosh, I don’t want to go through the rest of my life like this.” But in her book, it’s clear that Hollis is the one readers are supposed to empathize with, and the “addict” parents are the bad guys. She’s bold enough to blame them not just for their parenting, but also, indirectly, for her own substance abuse. Which begs the question: When two people have similar struggles but one is white and one is not, when one is wealthy and one is not, when one writes books and blog posts and hosts conferences and the other goes to McDonald’s hoping to see their child for an hour a week — who gets to be the good mom?

Despite its undeniable popularity, Girl, Wash Your Face has not been met with universal acclaim. One indication of how polarizing it is is how many of the book’s Amazon reviews rated “most helpful” — despite an overall rating of 4.8 stars — give the book just one star: at last count, 43 out of the top 50. “I don’t understand all the hype about this book,” one such review begins. “Rachel Hollis’s life experience is so near perfect and so far removed from that of the average woman, that there is almost nothing in this book that is actually relatable.” (This review garnered more than 50 comments, nearly all of them agreeing.)

“What about women that have lost a child? Those that have been beaten, verbally abused, raped, or shot at?"

Another popular review called the book “sanctimonious twaddle” and asked what Hollis could possibly offer women who have been through real hardships: “What about women that have lost a child? Those that have been beaten, verbally abused, raped, or shot at? What about those forging their way through life in male-dominated careers instead of party planning?” A third reviewer says that Hollis “lost me when she spends an hour talking about her super emotionally abusive relationship and then reveals that the abuser is now her husband.”

One top Amazon review describes the book as “page upon page of her repeatedly tooting her own horn and every so often throwing God a bone,” and plenty of dissenters can be found within the Christian online community too. “Reading Girl, Wash Your Face exhausted me,” wrote Alisa Childers, a Christian blogger and singer-songwriter. “Make no mistake, sisters. This book is all about YOU … Jesus offers us true joy and peace, but only after we realize that we are not the center of our own lives and we are no longer in charge.” Another Christian blogger wrote that Hollis “fails to identify the ‘lies’ as a secular worldview with all that entails, and her solutions are self-sufficient and not Jesus-oriented.”

I was struck by how liberally Hollis interpreted Bible verses to suit her message, like in a chapter about sex where she quotes Hebrews 13:4 (“Let marriage be held in honor among all, and let the bed be undefiled”) and says, “what I take away when I read that line is that the things that happen in my bed with my husband cannot be weird or bad or wrong.” No Biblical scholar on Earth would read that passage to suggest what she says, but to Hollis, traditional theology doesn’t seem to matter as much as finding Bible verses that seem to prop up the message she is communicating.

Hollis’s star seems to be on the rise — her next book, called Girl, Stop Apologizing, will be published in March — and her popularity shows no signs of waning; her next Rise conference, in June, is already sold out. From the ashes of her former life as a lifestyle influencer, Hollis is rising to lead an army of inspired women as a motivational speaker, media guru, business consultant, and tough-talking best friend, all in one. She has become a semi-secular preacher, and she has found her flock.

Following in the footsteps of tough-love doyens before her, Hollis’s audience of mostly white, middle-class women will probably be glad to have someone to tell them what to do, how to follow their dreams, to give them permission never to break a promise to themselves. But, in what many people would consider to be a moment of full-blown cultural crisis in the United States, are white, middle-class women the people who most need a champion telling them to prioritize themselves above all others?

There are so many systems in place to ensure that the people who are already down stay down: mass incarceration, voter disenfranchisement, rising health care costs, lack of public education, a narrowing path to citizenship for immigrants — the list goes on. And yet so many working and middle-class white people (not to mention billionaires) seem increasingly gripped with anxiety over the idea that what they have is not enough, or that what they deserve is somehow being taken from them by the undeserving.

“You are in charge of your own life, sister, and there’s not one thing in it that you’re not allowing to be there,” Hollis writes. But Hollis’s glibness makes clear that her “sisters” are only such if they look like her, share her padded bank account (and her priorities), and don’t venture too far into the real and wrenching difficulties of life.

The book never quite explains what it means to “wash your face,” but you get the idea that it’s a euphemism for toughening up, taking a good, hard look in the mirror, and getting out into the world with a kind of clear-eyed resolve. Rachel Hollis writes about that really well. I just wish she would actually do it. ●

Laura Turner is a writer in San Francisco.