BuzzFeed News has reporters across five continents bringing you trustworthy stories about the impact of the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

On the phone inside her San Francisco apartment, Lucía Abascal gently informed two brothers she had never met that they had been exposed to the coronavirus. Privacy rules, however, meant she could not tell them who had possibly infected them. She also told the siblings they’d have to stay inside for the next 14 days and monitor themselves for signs of a disease that has killed 59,000 Americans and counting. The brothers were frightened and Abascal talked to them about their fears.

It was a typical conversation for Abascal, a PhD student at the University of California, San Francisco. These days, she works in "contact tracing" — a public health strategy to contain the spread of disease by tracing backward from an infected person to others who may have been exposed so they too can be tested and quarantined.

As old as the smallpox epidemic and as detail-oriented as a piece of 18th-century embroidery, contact tracing is considered an essential component of reopening the United States and getting most people back to work, while isolating those most at risk of spreading the disease. At its best, contact tracing does more than just identify who has been unknowingly exposed; it can help pinpoint hot spots before they have the chance to spread widely.

But amid all the sobering statistics of the coronavirus pandemic in the US, here is one more: There are nowhere near enough Lucía Abascals. Experts estimate the country needs as many as 300,000 contact tracers to chart and break the chains of the pandemic. Currently, there are fewer than 8,000.

An attempt to automate the process by layering in the use of smartphone technology, meanwhile, has been complicated in the US by privacy concerns and the lack of a centralized approach.

China, Singapore, and South Korea have been lauded for their use of phones, in conjunction with old-fashioned shoe leather, to track infected people’s movements and trace clusters of the disease. Germany and Australia are launching their own programs.

Yet many are skeptical about how the US is going about it, or even whether the country would accept it. Germany is led by Angela Merkel, who was a scientist before she was a politician and whose advice is respected across the political spectrum. South Korea has a highly functioning central government, an advanced tech infrastructure, and a population willing to comply because it is scarred by memories of the SARS epidemic in the early 2000s. In China, the state already controls the data on people’s phones.

In the US, on the other hand, the populace is politically fractured and often distrustful of both science and technological surveillance. The few attempts in digital contact tracing already launched have been scattered across states, and lack compatibility; if you live in one state, you might not know if you were exposed to an infected person from another state — or even from another person in the same state but who was using a different app.

“It’s just techies doing techie things because they don’t know what else to do.”

In the coming days, Apple and Google are expected to roll out a highly anticipated new system intended to solve that problem. Yet, in an effort to assuage privacy concerns, it will only notify people they have been exposed but will not pass on important epidemiological information, such as who the infected person is and where they are, to public health departments. It does some of the work of contact tracing, but not all.

This has led to concerns that the US — which has already fumbled testing people and supplying health care workers with personal protective equipment — could wind up with yet another debacle. In a best-case scenario, digital contact tracing would be paired with and inform traditional efforts from public health departments, and it could stop the spread of the coronavirus in its tracks and save lives. But in a worst-case scenario, the US could become a wild west of incompatible contact tracing apps that vary from state to state and city to city, managed by companies with no public health experience that rake in cash via government contracts while providing the people who use them with a false sense of security.

“My problem with contact tracing apps is that they have absolutely no value,” Bruce Schneier, a privacy expert and fellow at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, told BuzzFeed News. “I’m not even talking about the privacy concerns, I mean the efficacy. Does anybody think this will do something useful? … This is just something governments want to do for the hell of it. To me, it’s just techies doing techie things because they don’t know what else to do.”

The concept of contact tracing was born in the late 18th century, when a physician in northwest England began interviewing and isolating local families to understand how smallpox was spreading. Since then, it’s been deployed to try to contain all kinds of contagions, from sexually transmitted diseases to the 2003 SARS outbreak to the swine flu pandemic of 2009.

In a number of countries, including South Korea and Singapore, old-fashioned contact tracing layered with high-tech use of apps, health monitoring, and location tracking has been credited with helping to stem the spread of the coronavirus.

Contact tracing is “one of the few successful traditional nonpharmaceutical interventions,” said Carl Bergstrom, an epidemiologist at the University of Washington. "This is a very old tool in public health. Doing it digitally obviously isn’t," Bergstrom said.

When the first cases of the coronavirus landed in South Korea, public health leaders worried the country could be hit hard by the virus. Instead, it emerged as an unlikely success story. In large part that was because South Korea, in marked contrast to the US, deployed testing on a massive scale. But officials in South Korea, who coupled testing with an aggressive approach to contact tracing, are credited with quickly identifying clusters where the virus might be spreading and getting people quarantined and treated.

The effort, dubbed the COVID-19 Smart Management System, is an attempt to reduce labor-intensive measures, such as interviewing patients to document their movements and whom they’ve encountered. The system culls data from 28 institutions, including law enforcement agencies, cell service providers, credit card companies, and more.

It also publicizes anonymized versions of patients’ travel histories using data from credit card transactions, GPS, and closed-circuit television footage. South Korea, where 95% of the population uses a smartphone, passed laws allowing the government to trace people’s movements in 2011, and revised it in 2015 in the wake of the outbreak of MERS.

Visitors to South Korea, meanwhile, are required to download a government-made app that tracks their movements and asks for information on symptoms the user is experiencing. In addition, private companies have also developed apps to alert people when they may be near someone who has been infected, including, for instance, a super-popular app called the Corona 100m app, which notifies the user if they come within 100 meters of the most recently recorded location of someone who has tested positive.

The effort has raised concerns from privacy advocacy groups — especially a plan to ask infected people to wear wristbands that would track their movements. Health officials have said citizens could be fined as much as 10 million won ($8,200) or face a year in jail for violating quarantine.

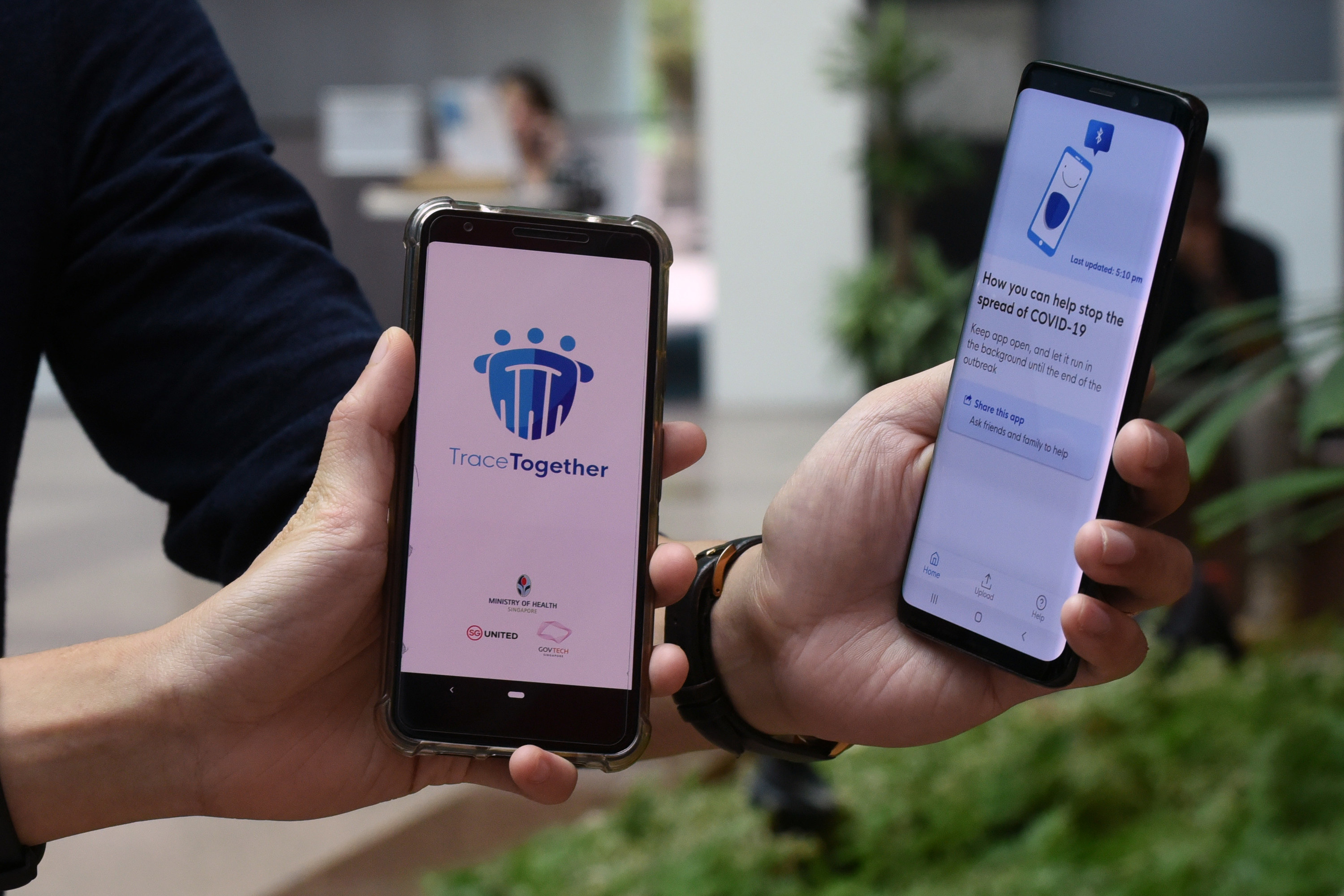

In Singapore, which has been widely praised for its quick efforts to contain the coronavirus, authorities distributed an app called TraceTogether. The app detects others nearby and keeps a record of these meetings on the individual’s device. Those records can then be handed over to contact tracing authorities if needed.

The country’s prime minister, Lee Hsien Loong, acknowledged that “there will be some privacy concerns.” But these, he said, had to be weighed against the benefits to combating the pandemic.

Both of these efforts were widely considered to have helped to slow the spread of COVID-19. But both were enhancements — not replacements — for traditional contact tracing. And both were done in countries where almost everyone who needed a test could get one. Singapore and South Korea might be technologically advanced, but a lot of this work isn’t automated and relies on old-school methods, including extensive in-person interviews. When a patient at a hospital in Singapore is diagnosed with COVID-19, an official will ask them about all of their movements for the previous two weeks to create a kind of historical map.

Although Singapore has been lauded for its handling of the coronavirus, it has seen a surge in cases in recent weeks, particularly among migrant laborers who often live in overcrowded dormitories where social distancing is essentially impossible. But the country’s extensive contact tracing has enabled it to reveal in some detail the extent of the outbreaks in these dormitories.

In India, contact tracing apps have already raised concerns over how infection data may dictate people’s lives. Citizens aren’t legally required to have the government’s contact tracing app installed, but states across the country are planning to issue digital passes to people within the app to let them move around after the country lifts its current lockdown. Indians may soon need to show that they have the app installed to board public transportation, take flights, or even to buy medicines.

“We use TraceTogether to supplement contact tracing — not replace it.”

And according to Nikhil Pahwa, editor of the technology website MediaNama, many gig workers are already being required to use the app in order to get jobs. The situation forces people to “make a choice between putting food on the table and installing an app that might violate their privacy,” Pahwa said.

Jason Bay, senior director at the government’s tech agency and product lead for TraceTogether in Singapore, is skeptical of any digital-only contact tracing method. No Bluetooth contact tracing system in the world, he said, could replace human-led measures.

“Any attempt to believe otherwise, is an exercise in hubris, and technology triumphalism,” he wrote. “There are lives at stake. False positives and false negatives have real-life (and death) consequences.”

“We use TraceTogether to supplement contact tracing — not replace it,” he added.

It is hard to fathom the US following such a top-down model. And yet, digital contact tracing has already begun here — an effort that has so far been decentralized and often uncoordinated from state to state and county to county.

“If you wanted to describe the federal response to date, there’s been a lot of finger-pointing and people not wanting to have the hot potato in their lap,” a Senate aide briefed by Google on its development plans told BuzzFeed News. “Given that environment, where no one wants to take responsibility for the thing, is an agency gonna stand up and say, ‘We’re gonna develop the app that every American is gonna use to get this [contact tracing] information’?”

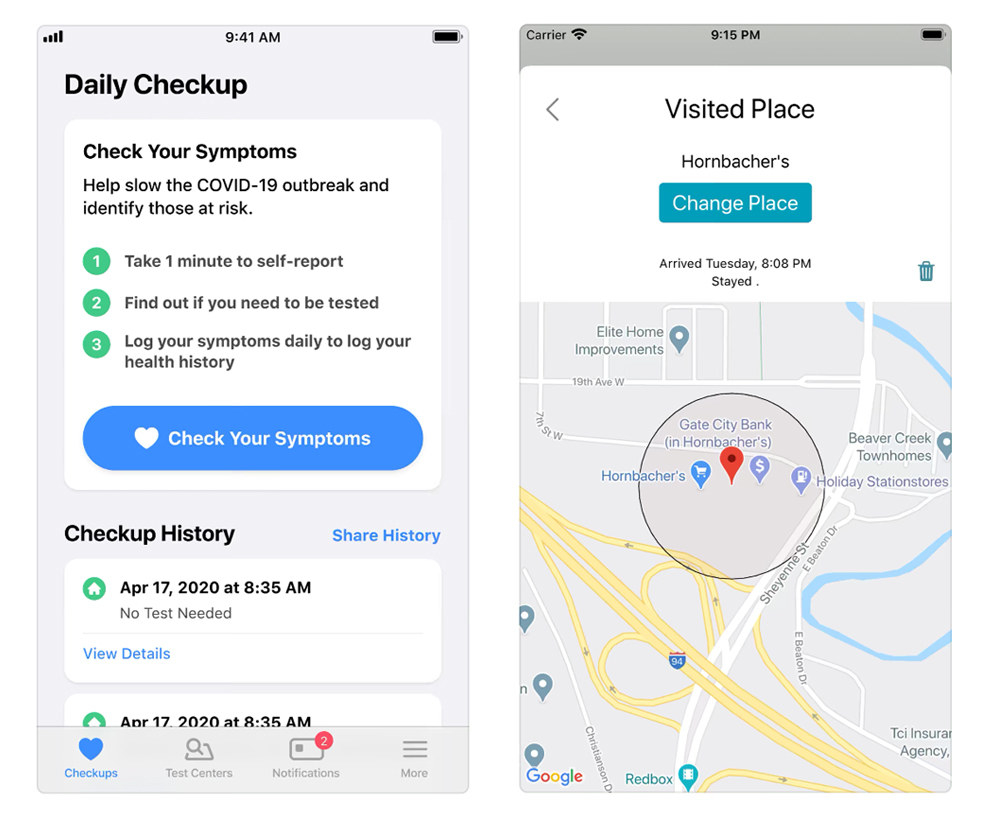

Last week, Utah launched a contact tracing app called Healthy Together, which aims to track the pandemic by getting people to report their symptoms and location data. The app was developed by a New York–based company, Twenty Co, which previously developed an app called Twenty - Hang Out With Friends, which let people view a map of nearby people to chat with.

Repurposed as a COVID-19 tracing app, the idea is that each user can, instead of using the app to hang out with friends, use it as a symptom checker, and public health authorities can see how many people with symptoms of the virus are in a particular area.

The app requests “a combination of GPS, WiFi, Cellular, Bluetooth, and IP address to detect and triangulate your location” in order to “detect if you've spent time near known COVID-19 cases,” according to its privacy policy.

It also requests access to Bluetooth — to "increase accuracy when you're in proximity to potential exposure events" — as well as your phone contacts. Healthy Together says it protects privacy by storing data about your location and symptoms for only 30 days.

The apps often stop at the border, even though the disease does not.

Meanwhile, Utah is woefully behind when it comes to the kind of boots-on-the-ground public health workers needed to really track the virus — and safely reopen. According to an NPR survey of state public health departments, Utah currently has 40 human contact tracers, but would need almost 1,000 in order to meet the state’s estimated need to respond appropriately to COVID-19.

North Dakota, similarly, unveiled an app called Care19 last week. The app says it uses “state-of-the-art GPS location data to help you trace the places you have visited.” If a person eventually tests positive for COVID-19, the app says, you can choose to share location history with the North Dakota Department of Health. Care19 also says it calculates a COVID-19 exposure "personal risk score," according to its privacy policy, which is shared with state government officials.

The app opens to a “Home Detection” page, where people are asked to enable location sharing so the app can determine if they're home.

The company that developed the app, ProudCrowd, had previously used its technology to display a heat map of where North Dakota State Bison football fans congregate on game days.

Like the app in Utah, it operates in a silo that just includes the Dakotas. The apps often stop at the border, even though the disease does not. Still, experts have lauded North Dakota for marrying the app with a huge number of contact tracers; according to NPR, the state has 250 on staff, which actually exceeds the number of human contact tracers that are estimated to be needed for the state’s small population.

In the absence of any kind of national effort, Google and Apple have attempted to create a framework for app developers that will provide the kind of compatibility that has been lacking.

Earlier this month, the companies announced that — in an unprecedented move — they were working together to create software updates for iOS and Android devices that make contact tracing more interoperable, accurate, and privacy-focused.

Most developers and privacy advocates have proposed using Bluetooth beacons — or radio signals that most smartphones use to send small files between each other at a short range — so that devices can log whom their owners have been near. This is, essentially, what the two tech giants have been developing.

Yet while Apple and Google are leading the development of the underlying technology necessary to make digital contact tracing tools — which they now refer to as “exposure notification” to distinguish from traditional methods — they have declined to develop actual contact tracing apps, fearful of losing public trust by overstepping privacy, according to sources at Apple. Instead, they’ve announced that they are delegating the development of the actual contact tracing apps to public health authorities and have been approaching local health departments about how to get apps up and running. Their solution, which sources at the companies and health agencies tell BuzzFeed News is still rapidly evolving, will be a two-phase system with phase one rolling out as soon as this week.

Initially, the system will require people to download apps from public health departments to do this exchange of information. Later, this exposure notification system will be built directly into phones’ operating systems. But it will work similarly in both cases, automatically notifying people that they have been around another individual who has self-identified as having tested positive for COVID-19.

It’s an ingenious system with three key features: decentralization, automated notifications and interoperability, a computing term which basically means different systems can exchange information. Because Apple and Google have provided a way for people’s phones to communicate with each other, it means that someone from one place can be notified if they’ve come into contact with an infected person from another — regardless of which apps they have on their phone. Think of it as being able to get a notification about a hot new TikTok, even if you only use Instagram.

Decentralization means there is no computer sitting somewhere that has a list of everyone who has tested positive and everyone they have been in contact with in recent weeks. Instead, data is anonymized and stored on people’s phones. This is important to privacy advocates wary of tracking by state actors or even, say, internet marketers or insurance companies. Finally, this anonymized exchange allows for automated notifications. Instead of a call from a contact tracer, you get a notification on your phone.

“They don’t know if there’s gonna be city- and county-level health apps, state apps, a federal app, or a US Red Cross app,” the Senate aide said. “They just don’t know yet.”

Yet this emphasis on privacy comes with a trade-off. Because the apps will not be capable of tracking location, or who exactly has tested positive, they will be unable to perform many of the very basic epidemiological functions that traditional contact tracers do. They would not, for example, provide the kind of data that would allow public health officials to interview everyone in an apartment building where a hot spot was flaring up to determine why some were infected and others were not. This is one reason the effort has been recast as “exposure notification” rather than “contact tracing.”

If you're someone who is seeing the impact of the coronavirus firsthand, we’d like to hear from you. Reach out to us via one of our tip line channels.

There is also a lot that is still just up in the air. When asked if people would only be able to submit verified COVID-19 test results, or if they have the option to self-report symptoms, company representatives for Google and Apple said that features like that would be determined by the public health authorities who actually release apps. But we don’t know which authorities will actually be in charge of these apps, whom they will contract with to build them, or if basic features will vary, say, from county to county or state to state.

Company representatives said in press calls that they would only release the apps’ programming interfaces to verified public health authorities, but could not say whether these public health authorities would be at the federal, regional, state, or local levels.

A Senate aide briefed by Google told BuzzFeed News there’s a reason the companies won’t say which authorities will be developing the tools: They don’t know.

“They don’t know if there’s gonna be city- and county-level health apps, state apps, a federal app, or a US Red Cross app,” the Senate aide said. “They just don’t know yet.”

While tech companies, government officials, and civil liberties watchdogs debate the best way to protect privacy while fighting the pandemic, San Francisco, one of the first cities in the US to experience the coronavirus outbreak and a global hub for tech startups, is pursuing contact tracing the old-fashioned way.

“We don’t have a treatment. We don’t have a vaccine,” said Mike Reid, an assistant professor of medicine at UC San Francisco, who has been overseeing the rapid hiring and training of the city’s contact tracing workforce since early April. “So the best thing we can do is: Every time we find a new case, we ask that individual to isolate and reach out to all their contacts and tell them you need to quarantine, not because you have an infection right now but because we worry you might develop an infection.”

San Francisco’s contact tracers now include more than 240 students, doctors, nurses, public health workers, and city employees who have been temporarily reassigned, including librarians, attorneys, and property assessors. Their task is to run down the coworkers, roommates, friends, and relatives of patients who test positive, ask them about their symptoms and living conditions, and enroll them in daily text alerts from public health authorities.

It’s a system that may be replicated across California. Gov. Gavin Newsom has announced he wants to dispatch 10,000 contact tracers across the state, in some cases redeploying existing state workers who have time on their hands because so much of the state is shut down.

As the California effort ramps up, Abascal, the San Francisco tracer who had to break it to the two brothers that they had been exposed to the potentially deadly disease, continues making her painstaking phone calls.

Abascal has a script to follow, but the conversations constantly throw curveballs.

She’s had to be a resource for people who don’t speak English and for a family of 10 crammed into a one-bedroom apartment. Others have asked her questions she can’t answer, from how to sign up for health insurance to how to navigate unemployment.

She was used to stark inequalities in her native Mexico and knew they existed in the US as well — but it has been jarring to come face to face with them here in one of the richest cities in the world.

A key part of the job, Abascal quickly learned, was earning the trust of scared strangers, keeping them on the phone, and reassuring them that she was not a scammer who’s out for their banking information or Social Security numbers. At the same time, the type of information she needs can feel quite personal to the people who answer her calls.

“Imagine if I called you. I know where you live; I know your phone number, but I can’t tell you who gave it to me,” she said. “People are wary about their privacy and information, so that’s an issue.”

Many calls require complex decision-making: Maybe someone’s living situation is unsafe, and the city needs to move them to a hotel to protect them and others — or maybe they need to get tested but have a disability that prevents them from leaving the house. Each situation is a little different.

As she watches tech giants promote the use of smartphones for contact tracing, Abascal is skeptical that they could be a cure-all.

Perhaps, she acknowledges, a Bluetooth-triggered app would be helpful for alerting people if they had been in a public setting, such as a bus or a Starbucks, with a stranger who later tested positive.

But, Abascal said, human contact tracers do something that cannot be totally replaced by an algorithm.

“We’re dealing with people that are scared, people that just lost their job. Many of them have family members in the hospital,” she said. “There’s a big part of the interview that’s conversation: ‘How’s your family doing?’ I don’t know how you would be able to do that computer-automated.”

Many interviewees start out skeptical but by the end of the call, thank the staffer for checking in, she says.

“The idea of having an app being able to do all the work we are doing is hard,” she said. “We’re not therapists, but still, if somebody is really worried, you’re able to tell them, ‘Don’t worry — we’re here to help.’” ●

UPDATE

This article was updated to reflect the full name of the app Twenty - Hang Out With Friends, which was called Hang Out With Friends in a previous version. It also clarifies that Twenty's existing technology was repurposed to create Healthy Together, not redeployed.

Stephanie K. Baer contributed reporting to this story.