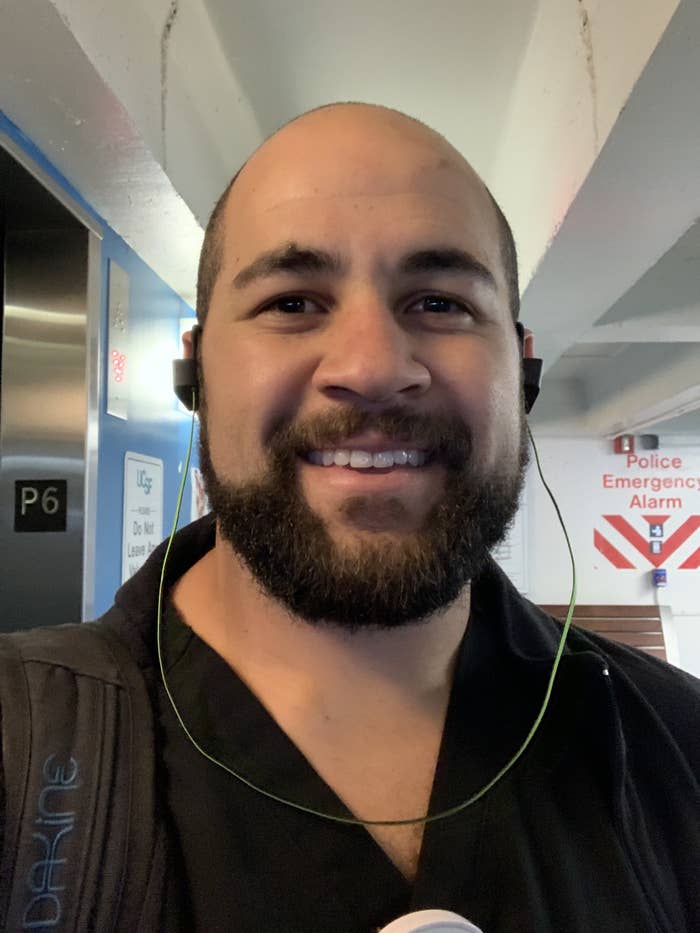

On Sunday, March 8, hundreds of emergency room doctors and medical school educators gathered at the Hilton in Midtown New York City for a conference organized by the Council of Residency Directors (CORD) in Emergency Medicine to discuss teaching strategies, innovations in research, and as a last-minute addition to the agenda, the growing coronavirus outbreak. Among them was Rosny Daniel, a 32-year-old emergency room doctor and assistant professor at the University of California in San Francisco.

By the end of the week, as the scope of the coronavirus outbreak in the US began to clarify, the world looked very different than it had that Sunday. Cities across the country were implementing containment policies. College and professional sports games were canceled. Disney parks shut down. The US banned travel from Europe. Panicked shoppers cleared grocery store shelves of pasta and toilet paper. America ground to a sudden halt. And Daniel, who had been working in UCSF’s emergency room to try to stem the outbreak, contracted the virus.

That Friday, March 13, after feeling ill, Daniel was tested for the coronavirus. The test results, terrifying enough on their own, ushered in an additional wave of guilt and anxiety due to another realization: A room full of emergency room doctors from all over the country were possibly exposed to the virus — either from Daniel or another attendee — before returning to their hospitals and possibly spreading the virus further.

“We absolutely didn’t know what was happening, nor where this was going to strike,” he told BuzzFeed News. “Everyone there, we're all people who care about the health and wellbeing of our communities. We just happened to have terrible, terrible timing.”

The risks were already apparent to conference organizers. In a “coronavirus update” posted to its website ahead of the meeting, which had at least 1,300 attendees from at least 34 states, they wrote, “In this time of public uncertainty and fear, it is especially important for emergency physicians to be seen as leaders and advocates for our patients, so CORD has no intention of canceling Academic Assembly at this time.”

Daniel reported his positive diagnosis to the conference organizers within minutes of receiving his test results on Saturday. Conference organizer DeAnna McNett didn’t respond to an email asking how many attendees were informed about the possible exposure and whether anyone else at the event had tested positive; an email to Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine’s general address also received no reply.

There’s a lot we still don’t know about the coronavirus outbreak. Our newsletter, Outbreak Today, will do its best to put everything we do know in one place — you can sign up here. Do you have questions you want answered? You can always get in touch. And if you're someone who is seeing the impact of this firsthand, we’d also love to hear from you (you can reach out to us via one of our tip line channels).

That hundreds of emergency room physicians and medical school professors well-versed in the risk of contagions were willing to gather in large numbers as recently as last week reflects just how quickly behaviors and attitudes in the US have shifted as the country struggles to catch up with an outbreak that has spread far faster and wider than American health officials have been able to measure. While it remains unknown whether any other conference attendees have contracted COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, their possible exposure to the virus reveals the dangerous consequences of the nation’s slow response to the pandemic.

If the conference had started two days later, Daniel said, he wouldn't have gone. But when he arrived at the conference that Sunday, the COVID-19 pandemic didn’t yet seem so dire, even to the medical experts gathered in the Midtown Hilton’s conference rooms. The number of confirmed infections in the US hovered in the low hundreds at the time, with the plurality of cases occurring at a nursing home in Washington state. Yet alarm bells were already sounding. On March 7 alone, New York City announced at least 13 new cases, questions were mounting over how close an infected CPAC attendee had been to the president, and Washington, DC, announced its first presumptive positive case.

Like most Americans, however, the doctors in attendance thought that the epidemic could still be contained through precautionary hygiene. They washed their hands rigorously and regularly, and avoided handshakes and other physical contact.

“There was more hand sanitizer than I’ve ever seen at a conference,” Daniel said.

Even then, he was wary. Throughout the conference's first day, between discussions on medicine’s role in social justice and enabling diversity in hospitals, he read news reports of the rapidly escalating number of infections in Italy and of the ongoing delays in US government efforts to implement widespread testing. By Monday, as some state governments began shutting down large events and universities began canceling classes, he felt his nerves tightening.

“I was already paranoid,” he said. “Friends I was with started to make fun of me for being paranoid. But Tuesday, we were all like, ‘holy shit.’”

That Tuesday the number of positive confirmed cases in the US began a rapid ascent. In New Rochelle, New York, just north of New York City, more than 100 people were diagnosed, leading Gov. Andrew Cuomo to declare a state of emergency, call in the National Guard, close schools, and designate a “containment zone” limiting large gatherings within a mile of a synagogue whose congregants were at the center of the local outbreak.

As the severity of the pandemic’s grip on the US dawned on Daniel and others at the conference, attendance on Tuesday dipped to about half of what it was the day before, he recalled. Some speakers dropped out. The doctors who remained took additional precautions. Daniel, for his part, chose to observe the two panels he attended standing against the back wall rather than sitting with others. Every cough in the room turned heads. By midday, “I was like, I can’t be here anymore,” he said. “I want to be at home. I don’t want to be in contact with anybody.”

He changed his Wednesday afternoon flight to 7 a.m. Though he felt no symptoms at the time — he doesn’t remember coughing while at the conference — he also knew that not all carriers of the virus exhibit symptoms, so like many others around the country, “I started to quarantine as soon as I got home” as a precaution.

Back home, Wednesday night seemed entirely normal. He watched Curb Your Enthusiasm in his bedroom in the San Francisco house he shares with two roommates, who each hunkered down in their own respective bedrooms. Though the three young men are friends, they didn’t hang out or watch television in the living room together that week, Daniel noted, a stroke of fortune brought on by a new commitment to social distancing.

He still felt fine Thursday morning and worked a 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. shift in UCSF’s emergency room, wearing full protective equipment, just as all of his patients were.

Then, shortly after he returned home that evening, he began to feel unwell. The coughing began around 7 p.m., accompanied by a wave of fatigue, a mild headache, and muscle soreness. The obvious thought crossed his mind, but he hoped the symptoms would fade after a full night’s sleep. It might have just been his asthma acting up, he thought. But he woke up feeling even worse. He called his supervisors at UCSF. They agreed that he should be tested for COVID-19.

By his own estimate, around 70% of Daniel’s work at the university hospital involves emergency room treatment, and in the preceding weeks, he’d come in contact with dozens of patients exhibiting flulike symptoms. This wasn’t unusual for this time of year, but as coronavirus cases began springing up on the west coast, Daniel and his colleagues wore protective equipment like gloves and respirator masks and washed their hands even more than they normally did. Patients wore the equipment as well. The most severely ailing patients were admitted into the hospital, the others discharged with orders to quarantine, medicate, and return only if symptoms worsened. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention didn’t approve widespread coronavirus testing until March 3, and even then kits were limited. Few of Daniel’s patients at UCSF were tested, and none that he encountered had been diagnosed as positive.

Across the country, “there's no unified response for who should be tested and who shouldn’t,” he said. “Everybody’s just trying to be hypervigilant.”

When Daniel’s test results arrived Saturday morning, 24 hours after he submitted a swab, he’d already braced himself: “You don’t test unless you know it’s a possibility.”

He couldn't be sure where he had contracted the virus. “I’ve worn all the proper personal protective equipment at work in the past weeks, but I live in a city, and I’ve been to the grocery store, the pharmacy. My best guess is I probably picked it up in New York, but I don’t know.”

Daniel’s positive test set in motion a series of actions that currently constitute the outbreak containment policy in most of the country. An official from the California Department of Public Health called him, asking him a series of questions from a checklist, including an accounting of every person he came into contact with over the previous two weeks. After that, Daniel contacted organizers of the New York conference, informing them that he may have exposed others and recounting the panels he attended. Organizers then began efforts to relay the information to attendees.

“I think they’re kind of dealing with it internally,” Daniel said. “There’s no universal protocol across the country.”

Daniel took it upon himself to warn as many people as possible that he may have exposed. He reached out to friends, relatives, and coworkers. He broke the news in two group chats he shares with colleagues he saw at the conference — a few have been tested, all with results that came back negative. He wrote a post on Medium to make public his diagnosis and raise awareness about the risks facing health care workers. With the precautions he took throughout the conference, he believes it's "unlikely" he passed the virus to any of the doctors there. He may never know who he caught the virus from, nor whether he infected anyone else — nobody he knows personally has been diagnosed with the infection.

“My concern is that if people are quiet about this, it’s just going to get worse,” he said.

One of his roommates left their house to stay with a significant other. The other remains. Daniel said that he is careful to stay in his bedroom as much as possible, leaving only to use the bathroom — the house has two — or get food from the kitchen. He wears a face mask whenever he steps out of his room and carries around a container of Lysol wipes, scrubbing any surface he comes into contact with, light switches, walls, countertops. “Before this, I didn’t realize how many things I touch over the course of a day,” he said.

Daniel can’t be sure what comes next. In an interview with BuzzFeed News on Monday, he said that his symptoms remained mild. His dad calls to check in. His brother and sister-in-law live nearby and are able to bring groceries if needed. Though he is quick to note that knowledge of COVID-19 remains limited, he hopes that his ordeal earns him immunity from the strain or at least some resistance. If that is the case, he said, he is thankful that he caught it early, because he sees a long road ahead.

“We’re at the beginning of this and people are going to get sick, and we’re going to lose a lot of our health care force” to the illness, he said. “I’m looking forward to stepping up when times get tough.”