It’s so brutally cold in the Midwest right now, with subzero temperatures lingering for days, that schools and businesses are closing, mail carriers aren’t delivering mail, transit workers are lighting fires to keep trains running, and people are dying.

The “polar vortex” is blasting cold air normally found around the North Pole into the middle of the country. These US-bound Arctic blasts have become more common in recent decades, and some scientists say global warming is to blame.

Although this climate link is still under debate, what’s indisputable is that over the coming years and decades, climate change will harm much of the inland United States. Sea levels and hurricanes may get most of the attention, but a warming planet will have impacts throughout the country, from the South to the Great Plains to the Midwest, causing fires, flooding, heat waves, beetle outbreaks, changes to snowmelt, and crop failures that could result in billions of dollars in losses by 2100.

“Too many people see climate change as a coastal issue,” said Julie Cerqueira, executive director of the US Climate Alliance, a governor-led group responding to the climate crisis. “And we forget that droughts, heavy flooding, wildfires — that these are all issues the rest of the country faces.”

“The impacts of sea level rise are so clear and so targeted,” Kimberly Hall, a climate change ecologist at the Nature Conservancy and an author on the Midwest chapter in the 2018 National Climate Assessment, told BuzzFeed News. “It is much harder to pinpoint one driver of impacts in the Midwest because you’ve got so many things interacting.”

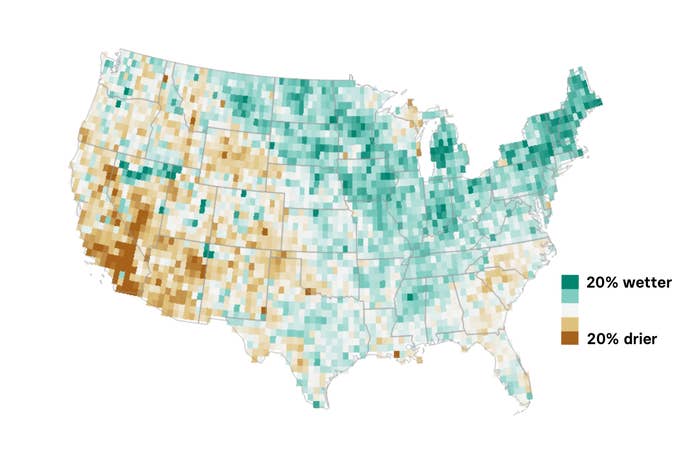

The impacts range from the shifting ranges of plants and animals to longer pollen seasons and even a cross-country ski race canceled due to lack of snow. But one of the most important and noticeable effects in the Midwest is an increase in rain, especially heavy rain, scientists say.

“One of the important trends in the Midwest has been the increase in heavy rainfall and associated flooding,” mainly in the spring and summer, said Kenneth Kunkel, a research professor at North Carolina State University and another National Climate Assessment author.

The uptick in heavy rain isn’t a trend unique to the Midwest, but it is particularly pronounced there. The amount of rain falling during intense events in the Midwest since 1991 has been more than 30% above the 1901–60 average, according to the latest National Climate Assessment, and the only other region to see more dramatic changes is the Northeast.

When the ground gets too wet and soggy in the spring, farmers delay planting crops. Rain can also wash out soils on farms, triggering nutrient- and chemical-filled runoffs into lakes. One way farmers are minimizing runoff is by interspersing crops with strips of natural prairie vegetation, said Kunkel, which stays year-round and can effectively “catch” runaway soils.

Beyond farming problems, heavy rains are flooding cities, contaminating drinking water, and damaging buildings. “Like a lot of climate change effects, it’s not necessarily the effect itself, but it’s the interaction between the effect and changes we’ve already made in the landscape,” said Hall. Researchers estimate the cost of updating Midwestern urban stormwater systems to better respond to damaging storms could exceed $500 million by 2100.

And like widespread rainfall changes, the entire country has been warming — and some of the worst-hit places are inland states. The most dramatic warming so far has occurred in Alaska, the Northwest, the Southwest, and the Northern Great Plains. It was so hot in Arizona in July 2017, for example, that some flights were canceled at the Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport.

The combination of increased warming and dry conditions, meanwhile, has helped spur more damaging wildfires and the proliferation of tree-killing bark beetles in Colorado forests, according to Thomas Veblen, a distinguished professor of geography at the University of Colorado Boulder. Warming is also shifting snowpack patterns in ways that, if continued as projected in the future, could lead to less water flowing through the Colorado River Basin.

The future projections for warming are particularly dire for the Midwest. Take the city of Chicago. In a scenario with moderate warming, the city could see up to 23 days per year above 100 degrees Fahrenheit by the century’s end. But in a much warmer scenario, the city could see more than 60 days, or about two months, per year by the end of the century. “This is something you will see over and over with climate change,” Brenda Ekwurzel, a director of the climate and energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, told BuzzFeed News. “The worst-case scenario is way worse than when we reel off these averages” of possible future impacts.

More warming, likely leading to more frequent or damaging heat waves and droughts, can also hurt crop production. One of the reasons the Midwest is an agricultural hub is because of good soils that can hold a lot of water, allowing them to persist through dry periods. But during a serious enough drought, those soils get depleted of water, Kunkel said, and the concern is this “depletion will happen faster because at higher temperatures more water evaporates.”

In parts of the Midwest, the changes to precipitation and temperature may actually have some positive impacts, Kunkel said, such as extending the growing season of certain crops. A 2017 study projecting future economic climate impacts showed that many northern states are on track to experience more benefits than problems by the century’s end.

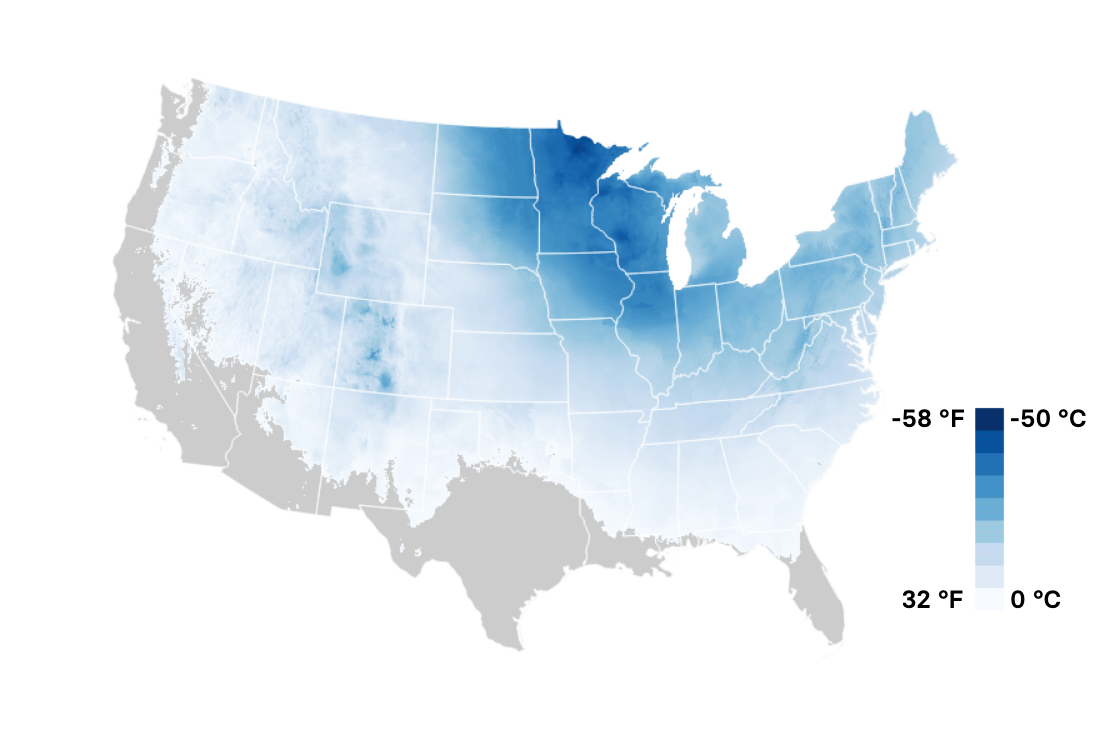

So: extreme rain, extreme heat, and maybe extreme cold, too. In the past two days, due to the polar vortex, temperatures have plummeted to –21 degrees Fahrenheit in Chicago, –56 degrees Fahrenheit in Cotton, Minnesota, and –31 degrees Fahrenheit in Detroit. Although polar vortex visits to the US aren’t new, they’ve become more frequent in recent decades. A theory gaining traction among climate scientists is that melting sea ice is disturbing the normal Arctic air flow pattern.

“So, ironically you might have some really cold days in the Midwest despite global warming,” Ekwurzel said.

A new analysis by the Washington, DC–based nonprofit the Brookings Institution found that of the 15 states hardest hit by climate change — including Arkansas, Oklahoma, Arizona, and other inland states — 14 had voted for President Trump, who does not believe in human-made climate change.

“Democratically leaning districts will see less damages going forward than Republican ones,” Mark Muro, a senior fellow and policy director of Brookings’ Metropolitan Policy Program. “So, in that sense, Republican districts are voting against the interests, in terms of climate harm.” (That said, a wave of Democratic governors were just elected in the Midwest, and even some Republicans are beginning to talk about climate action.)