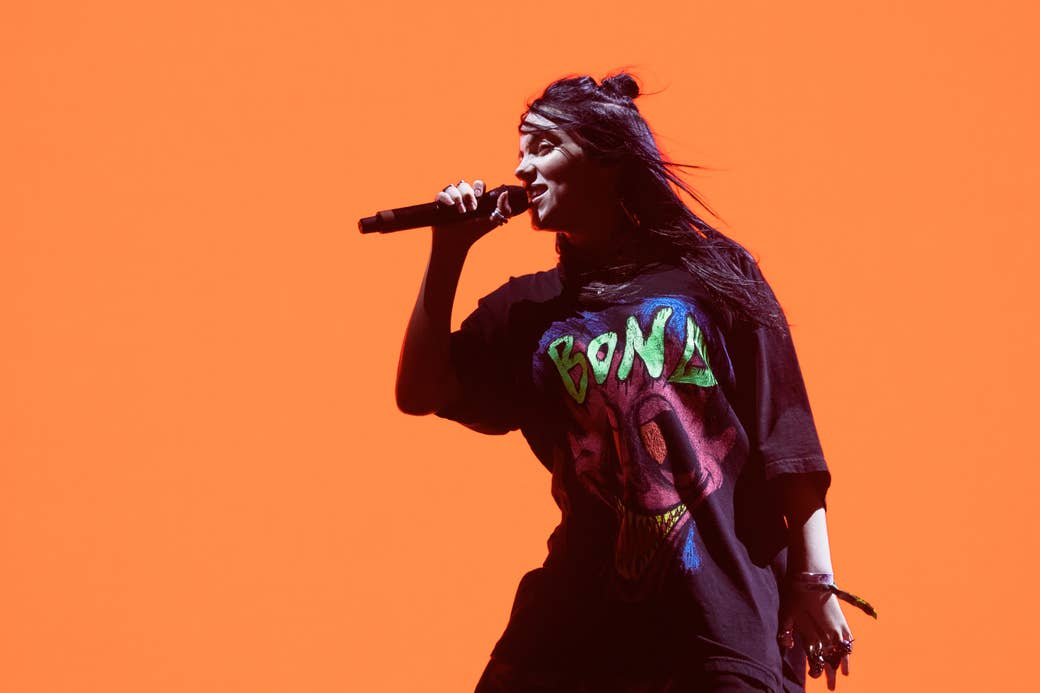

During a recent sold-out show in Minneapolis, Billie Eilish burst onto the stage, jumping around with anarchic glee, singing her bouncy, brooding hit “Bad Guy.” As her trademark tarantulas crawled around on a screen in the background, her audience sang along. “My fucking shin splints are acting up right now,” she told the crowd during a break. “You know how annoying that is?” After taking a sip from her water bottle, she casually asked, “Who wants this, by the way? I just drank out of it,” before tossing the bottle, wedding bouquet–style, into a knot of screaming fans with their arms outstretched.

Eilish seemed to explode out of nowhere earlier this year. Her first album, When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go?, debuted at No. 1 in April and has hovered at the top of the charts since then. It has now sold 1.5 million copies, second only to Ariana Grande’s Thank U, Next this year. And while the 17-year-old had already conquered streaming last year, in the past couple of months, “Bad Guy” also shot up the Billboard Hot 100.

This week “Bad Guy” became the longest-running No. 2 hit since Missy Elliott’s “Work It”; it’s been kept out of the top spot for months by the nationwide cultural phenomenon that is Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road.” After a Justin Bieber remix and a new marketing push, “Bad Guy” looks like it might soon hit No. 1. In some ways it’s not surprising that the song, which (not counting an intro) opens Eilish’s album — and her concerts — has become the most radio-friendly version of her sound. Like one of the other most-streamed songs from the album, “You Should See Me in a Crown,” the song’s defiant chorus is instantly anthemic. “I’m the baaaad guyyyy,” she declares, with the refrain distorted into menacing electronica — and then punctuated by a deadpan, eyerolling “duh!” That combination perfectly captures her signature pop style: goth-lite menace leavened with cheeky teenage humor.

That knack for blending different tones in unexpected ways is also expressed in her personal style: part punk, part ’90s hip-hop, featuring baggy tracksuits and a revolving kaleidoscope of hair colors. Eilish’s spare, surprising music videos — she eats a spider in the one for “You Should See Me in a Crown,” and pitch-black tears stream from her eyes in the “When the Party’s Over” video — have also been key in defining her spooky persona.

Eilish has, at 17, been getting the kind of press most musicians spend their whole careers waiting for. The Fader jumped in first, back in March, with a cover story asking, “Who’s Billie Eilish?” Since then, the New York Times has said she’s “Not Your Typical 17-Year-Old Pop Star. Get Used to Her.” Billboard called her “The New Model for Streaming Era Success,” while Rolling Stone anointed her rise as “The Triumph of the Weird.” (Even the old-school rockists of NME admitted that Eilish is “The Most Talked-About Teen on the Planet.”)

This degree of hype around any artist will inevitably be met with some criticism, and in the music industry corners of Reddit and YouTube, some commenters have expressed the suspicion that Eilish might be — in SoundCloud parlance — an industry plant. (She’s not, but more on that later.) These conversations are arguably part of broader anxieties about how pop stardom has changed in the age of streaming. Many have argued that pop has seemingly fragmented into micro stardoms. Yet Eilish has managed the hat trick of winning at streaming, cultivating a rabid, album-buying fanbase (she has 34 million Instagram followers), and garnering the kind of magazine covers and network TV appearances coveted by old-school monoculture-era pop stars. How did this all happen, and is it all as groundbreaking as it seems?

As the cover profiles have trickled out, public fascination with Eilish’s life story has only grown. She grew up in Highland Park, Los Angeles, and her parents were actors; her dad, Patrick O’Connell, had small roles in The West Wing and Iron Man, while her mom, Maggie Baird, was on a soap opera and later did voice work. Both now travel with Eilish on tour and work as part of her team.

Her father recently told the New York Times that he was “completely swept away” by Hanson, the boy band of brothers whose hit “Mmmbop” swept the nation in 1997, the year Eilish’s older brother, Finneas, was born. O’Connell credited the band’s musical confidence to their homeschooling and that “they’d been allowed to pursue the things that they were interested in.” That was part of what inspired him to homeschool his own kids, and Eilish and her brother were encouraged by their parents to express themselves through whatever forms of creativity they chose. So, to whatever extent Eilish’s parents are “stage” parents, they were never stern taskmasters in the Joe Jackson mold, but something hipper and hippieish.

The revelation of Eilish’s parents’ industry background is part of what has also prompted the now-usual online chatter about connections, privilege, and authenticity in the music industry. These questions about cultural capital and advantage are not in and of themselves unfair, though they often seem to coalesce around young white women pop stars like Lana del Rey, a major Eilish influence.

The notion of the “industry plant” seems to have gotten extra currency in the age of SoundCloud, because the platform supposedly democratized who gets to “make it” in the music industry, especially in hip-hop. And as Jon Caramanica writes, “Eilish is, more or less, the first SoundCloud-rap pop star, without the rapping.” A lot of Eilish’s poses, fashion, and vernacular come from hip-hop. (She recently told the Times, “Everyone needs to give hip-hop credit — everyone in the world right now.”) The “plant” term is the newest way of addressing the persistent class and racial inequalities that position some artists — namely, richer, whiter (and straighter) ones — to succeed ahead of others. And capital comes in different forms, including cultural capital, like having industry-adjacent parents.

There is now a new guard of gatekeepers — and Eilish was backed by them early on in her career.

Eilish seems aware of the skepticism and has pushed back on it, arguing that, despite her industry connections, she didn’t grow up as wealthy as some critics might believe. About her birthplace, she told NME: “Highland Park has become popular now, but growing up there, it was not like that at all. There were gunshots and shit, y’know – it was really sketchy.” In response to a direct question about her background, she noted, "Hearing, like, my parents were actors — OK, no disrespect, but they weren't, like, famous actor celebrities. They were working actors."

Eilish herself didn’t like acting when she tried it, but enjoyed the more raucous energy of performing background dialogue for movies like Diary of a Wimpy Kid, Ramona and Beezus, and the X-Men series. She became part of the Los Angeles Children’s Chorus and took dance lessons. Meanwhile, Finneas, who is now the writer or cowriter and producer of all of her work, did become a child actor, with roles in the movie Bad Teacher and the high-profile shows Glee and Modern Family.

Both siblings loved music growing up. Finneas started a band, which led to Eilish’s pop star origin story — one that has quickly achieved the status of myth. It goes like this: Her brother, then 17, had written the love song “Ocean Eyes” for his own band. But he decided to have his then-13-year-old sister, who had a knack for singing radio hits and making them her own, record it instead. “We put that song up with no expectations at all,” she remembered. “We literally posted it so we could send a link to my dance teacher. It got 1,000 plays after a day, and me and my brother were stoked. We thought, Oh my god, we’re famous.”

Everyone loves an underdog story, and that kind of narrative — of being an ordinary teen plucked out of obscurity by a YouTube video or SoundCloud song — has become the defining rags-to-riches celebrity story of our moment. It’s the story of SoundCloud rappers like the late, Florida-born XXXTentacion (Eilish is an admirer), whose song “Look at Me!” was propelled from SoundCloud onto Billboard’s Top 40. This is also the story of Lil Nas X. The Atlanta then-teenager’s independently produced, genre-crossing country-trap hit “Old Town Road” came out of nowhere when it was released in December of last year. And while it faced genuine resistance from country gatekeepers, the song enjoyed a meteoric rise (largely propelled by TikTok) to the top of the charts in a matter of months.

But Eilish’s rise took much longer, and her trajectory wasn’t actually the organic internet phenomenon many believe it to be; rather, it was more of a carefully planned, old-school corporate launch. Much has been made of the theory that Eilish has bypassed traditional industry gatekeepers on her way to the top. But it would be more accurate to say that in 2019, over a decade after SoundCloud and Spotify reshaped the music industry, there is now a new guard of gatekeepers — and Eilish was backed by them early on in her career.

“Ocean Eyes” wasn’t some immediately career-making viral hit, but the song reportedly made enough of an impact for Finneas’s manager to reach out to him and talk about Eilish’s potential in November 2015. By early 2016, in a deal engineered by her brother, she had been signed to the London-based A&R and creative services company Platoon (bought by Apple in 2019), a company that helps package artists before they go on to major label deals. Eilish got her own publicist, who connected her to the Chanel fashion label, and her own stylist, Samantha Burkhart, both of whom helped shape her image.

“Ocean Eyes” was rereleased with a new video in late March 2016, and it was clear in the clip that Eilish is not just a vocalist but a full-on performer. Her beautiful voice is just one part of her arsenal; she stares at the camera as she performs the dreamy ballad in the pastel purple, professionally directed clip; her minimal hand movements add a delicate touch. Finneas’s production on the track is sparkly and moody.

By August 2016, Eilish was signed to the Darkroom, a label and artist management company that works with Interscope. The newer label is led by Justin Lubliner, a now-28-year-old who had carefully studied the way hip-hop artists like Travis Scott and Chance the Rapper had reshaped music stardom for the age of streaming, relying not on one big hit single but on crafting a whole persona and distinct aesthetic — not unlike the kind Eilish and her brother were developing.

For all the comparisons of Eilish to the precocious stardom of someone like Lorde, there was no breakout, defining single like “Royals” to capture people’s attention — and that was by design. “We never wanted anything to be bigger than Billie the artist,” her manager told the Times. Instead, working with Finneas, she crafted her first EP, Don’t Smile at Me, which was released in the summer of 2017. The EP had nine varied songs, allowing fans to get into whichever side of Eilish they liked.

Some of the songs, like “Idontwannabeyouanymore” — which became the second most-streamed after “Ocean Eyes” — were in a similar ballad mold. But the EP also transformed Eilish, as one blog put it, from pastel pop star to dark pop artist. The smooth, lilting pop sounds of “Bellyache,” which begins with “Ocean Eyes”–like melodies, belie the fact that the song’s story is told from the perspective of someone who has killed her friends and is feeling guilty about it. (The lyrics “The way I wear my noose / like a necklace,” were brought out in the EP’s cover image).

Eilish started becoming something of a corporate project for Spotify and was promoted on “Today’s Top Hits,” Spotify’s most popular playlist, which is usually focused on radio songs. Her sound fits into the new genre of Spotify “streambait,” defined by Liz Pelly, writing for the Baffler, as “mid-tempo, melancholy pop,” influenced by Lana del Rey, whose “singing style and that bleakness, and the hip-hop influenced production” shaped a new aesthetic.

The piece made clear that a new generation of artists who grew up with streaming were in a kind of synergistic feedback loop with the streaming company’s aesthetic. And it was through Spotify promotion that Eilish really took off. Last year, she was already being trumpeted as the youngest artist to hit a billion streams, and that was still before the release of her first full album this past April.

Eilish and her brother carried their quirky songwriting sense for interesting narrators into her album. “Bury a Friend,” told from the perspective of the monster under the bed, inspired the album’s entire aesthetic, including the title. There’s a broad range of musical styles to pick from, enough to hit multiple Spotify playlists. (To promote the album, Spotify set up a pop-up “enhanced album experience” in downtown Los Angeles, entirely curated by Eilish herself, featuring different moods and atmospheres for each song for her fans to experience.)

There’s a theatrical quality to the album; in the song “Wish You Were Gay,” a recorded audience suddenly bursts into laughter and applause, and Eilish is very much a performer as she snarls, exudes cabaret-like whimsy, or uses her indie pop voice. (Her vocals are startlingly intimate, as if she’s whispering straight into the microphone, ASMR-style.)

The hauntingly beautiful “I Love You” evinces the cinematic minimalism of Sufjan Stevens, and “Xanny,” in which she sings about not needing meds, has been cited as part of her open discussion of mental health, including her experiences with anxiety, self-harm, and depression.

That openness about her life and her very online (and close) relationship with her fans also define her stardom.

There’s something unique about the collaboration between a teenager and her older brother. In combining Eilish’s own specific perspective, including her fascination with horror, with insights from the producer who knows her best, they achieve an end result that is undeniably fresh and distinctive.

You can’t be a pop star without stans — and Eilish now has plenty of them. Many people first discovered her through her music but became even more invested in her through her Instagram. Aaron, an 18-year old from Germany who now runs the @thereretheavocados fan account, first watched a YouTube video of Eilish on a channel called “Colors” in 2017 when her EP came out.

“Since I watched the video I totally fell in love with her,” he told me via Instagram DM. “I listened to her EP, started following her on IG, started following other fan pages, learned about her brother Finneas and how they make music together and then I finally went to her first concert in Berlin on her first tour where she came out after every show and met everyone.”

He started the account, which now boasts 161,000 followers, because, he said, “I just needed a place to share my concert videos because I didn’t want to annoy my friends with them. And I wanted to support Billie and her family and show my love for her.”

Maya, a 16-year-old from Australia who runs the @billiefuckingeilish fan Instagram account (437,000 followers), said that through Instagram she’s been able to communicate with Eilish’s mom (who follows her) and Eilish’s stylist (who’s “actually a very nice person”) — which speaks to the way Eilish, despite her aura of transgression, has also managed to create a kind of wholesome family brand.

Pop in the streaming era is defined by weirdness and variation from the old mainstream pop norms.

Celebs have been giving their fans the illusion of “really” knowing them through their social media feeds for a long time, but Eilish has grown up with these platforms — so her brand has always been completely intertwined with them, and, as such, she knows what fans want from her in that context.

“I think something special about her is that she grew up in the same generation as a lot of her fans have. That really shows when it comes to her interaction with us,” said Maya. “She never fails to stay on the same level of us in a way” because she “always give[s] us new and exciting things — whether that’s new music, or just a quick selfie, or even liking fans’ posts.” One fan recently pranked the singer by creating a fake Eilish Instagram story in which she farts live; Eilish debunked it by explaining, jokingly, that her farts don’t sound like that.

Another running theme among fans is Eilish’s versatility and ability to surprise. “You think you can guess what she'll do next, and then she goes and proves you wrong,” said Em, a 15-year-old from Europe who’s one of three fans running the @eilishupdates Twitter (with almost 100,000 followers).

Constantly surprising fans, of course, means that Eilish is also setting up big audience expectations for content and engagement in the future. In the wake of the “album era,” the gaps between most artists’ projects have become shorter and shorter as the internet demands more and more content. (Ariana Grande, for instance, recently released two albums, Sweetener and Thank U, Next, within six months of each other, finishing the second album in two weeks. It yielded her first No. 1 hits.) Eilish, from her debut single to her EP to her album, has constantly kept fans engaged with new music styles, lyrical perspectives, hairstyles, and outfits.

Much of the media coverage of Eilish’s career so far suggests that she represents a new vanguard of the music industry, especially because of the way she subverts expectations of how white teen girls should use their voices — writing about more than just boys, for instance. Yet at the same time, the fawning press brings to mind a recent essay about the way art featuring complex, even supposedly unlikable straight white women artists and characters — like Lena Dunham’s Girls or Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag — gets praised and universalized as representing larger truths about an entire generation in a way that is ultimately reductive.

Something similar has happened as Eilish’s weirdness is slotted into that role for Gen Z. Often the music journalist gaze constructs younger pop stars to fit those journalists’ own narratives. There is a tendency among the older millennials who write about Eilish to contrast her (favorably) with Britney Spears. (Eilish herself has done this.) But Spears’ teen pop heyday was 20 years ago. Now pop in the streaming era is defined by weirdness and variation from the old mainstream pop norms, as evidenced by the trap-country hit by a black gay artist that has kept Eilish from the summit of the Billboard charts. Pop stardom has also been queered by artists like Halsey and Troye Sivan, while reggaeton helped Latinx pop star Becky G break YouTube records. BTS’s K-pop has broken records in the US as well.

And yet the relationship between unconventional musical success and stardom isn’t clear-cut. It was only after “Old Town Road” became an enormous hit that the record industry — and the mainstream press — took notice of Lil Nas X, and most of the coverage of his music has been oddly defensive in tone — not universalizing his story as a generational artist, but explaining that he’s more than a meme artist or one-hit wonder.

Regarding her distinctive fashion sense, which sometimes involves wearing four coats at a time, or pants on her arms, Eilish explained, “I don't dress casual anymore; it has to be crazy out there. I like being judged so I don't care if people hate it — it makes me even happier if they hate it because then I'm in your head and you're thinking about it and that's on you, bro.”

But Eilish’s booming popularity — even as someone who’s apparently “not like other girls” — ultimately raises questions about who gets to refuse pop conventions while still being centered as a monocultural pop star. That a traditionally beautiful white girl has been elevated as the face of difference and “weirdness” in 2019 reminds us that as much as things change in pop, they also stay the same. ●