Elizabeth Holmes’ legal team portrayed failed Silicon Valley entrepreneur as a confident leader who, even as her doomed startup Theranos crashed and burned, stuck with her belief in the now-discredited blood-testing technology as they turned the fraud case over to jurors on Friday.

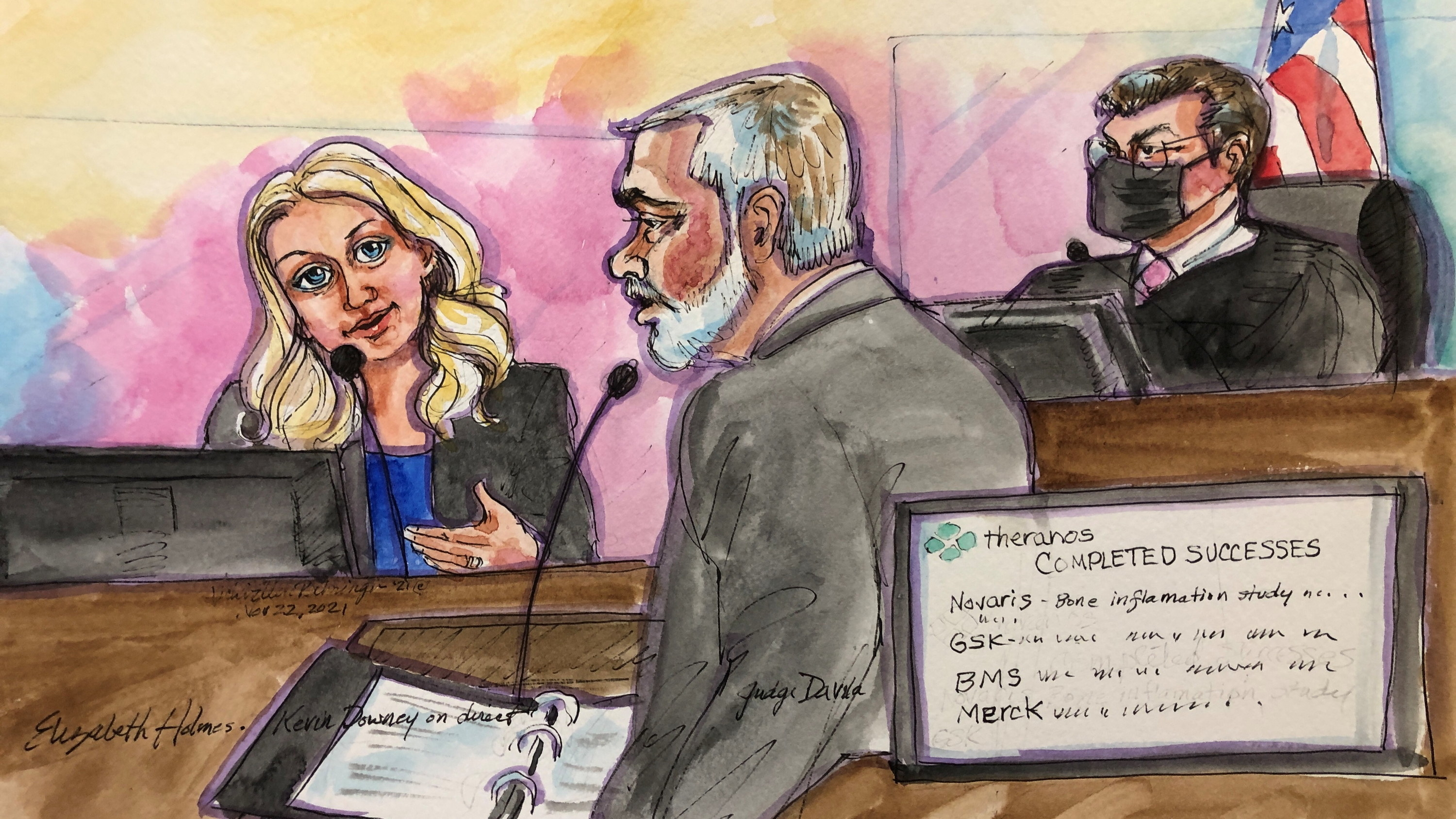

“At the first sign of trouble crooks cash out, criminals cover up, and rats flee a sinking ship,” Holmes’ attorney Kevin Downey said during closing arguments. But Holmes didn’t do any of that. “Why? Because she believed in this technology. She stayed the whole time, and she went down with that ship when it went down.”

And yet, it's that devotion to the company Holmes famously dropped out of Stanford University at age 19 for — so that she could focus her life around its success — that federal prosecutors say provided the former CEO and founder with the motivation to resort to fraud.

“She did this on behalf of the company,” Assistant US Attorney John Bostic told jurors in a rebuttal to the defense. “She committed these crimes because she was desperate for the company to succeed.”

Now, a 12-person jury will decide if Holmes, 37, intentionally defrauded investors and patients by making misleading and false statements about the capabilities of her blood-testing technology, the company’s work with the military and pharmaceutical giants, and the accuracy of its test results. The jury were given instructions late Friday after a trial that stretched more than three months and featured testimony from more than 30 witnesses, including Holmes. Over the course of seven days, the former CEO and founder of Theranos — whose downfall attracted intense media coverage and public scrutiny — denied that she’d ever tried to mislead anyone, expressed regrets, deflected blame, and accused her former second-in-command and ex-boyfriend of psychologically and sexually abusing her during their decadelong relationship.

Her fate will likely hinge, legal experts say, on whether her testimony raises enough doubt in jurors’ minds about the evidence prosecutors laid out. And while Holmes’ statements about abuse were the most striking and emotional part of the trial, the jury could find that even if she were a victim, it doesn’t absolve her of responsibility for what she said as CEO.

“The jury may not find a sufficient connection between the alleged abuse and whether she was able to have the intent to defraud,” Diane Birnholz, a former federal prosecutor and lecturer in law at the UCLA School of Law, told BuzzFeed News. “Both can be true: She could have been abused, and she could still have intended to defraud those investors and patients.”

Prosecutors have alleged that Holmes conspired with her ex-boyfriend Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, who was Theranos’s president and chief operating officer, to defraud investors as well as patients, and doctors who used the company’s laboratory services. Holmes is charged with nine counts of wire fraud and two counts of conspiracy to commit wire fraud. Each count carries a sentence of up to 20 years in prison if she is convicted. Balwani is facing the same charges as Holmes and is set to go on trial next month.

The former Silicon Valley entrepreneur had sought to disrupt healthcare with Theranos’s propriety machine, which she claimed could run hundreds of tests on just a few drops of blood. The company’s device was supposedly faster, cheaper, and more accurate than all other blood-testing lab equipment on the market and promised to bring critical diagnostics into drugstores, homes, and even battlefields. But as a Wall Street Journal investigation revealed in 2015, in reality, the machine could run only a small number of the tests, and its results were often inaccurate or unreliable. Instead, Theranos relied on commercially available machines to run the majority of its tests, diluting the drops of blood to increase volume for some tests and using much larger samples drawn from patients’ arms for others.

“The real version of Theranos, where the defendant went to work every day, was dramatically different than the rosy picture that she was painting for others,” Bostic said.

That, however, did not negate the fact that Holmes and others at Theranos worked hard to achieve her vision. “The disease that plagued Theranos wasn’t a lack of effort,” Bostic added. “It was a lack of honesty”

Over the course of his closing arguments on Thursday and Friday, Downey offered a different view of the evidence and tried to poke holes in the prosecution’s narrative, as he argued that the former CEO wasn’t trying to hide anything. He showed jurors multiple slides of names of former employees, doctors, and others that the government did not call to the witness stand to suggest that the government’s portrayal of Theranos was not the full story. He also tried to distance Holmes and her actions from some of the investors she is alleged to have defrauded, suggesting that they had limited direct contact with her and didn’t rely on the issues highlighted by prosecutors — like misrepresentations about Theranos’s work with the military and drug companies — in their decisions to invest.

With regard to the troubling test results that multiple patients testified about at trial, Downey said that by the time Holmes was informed of the issues, they had been resolved.

And while Holmes admitted that she had made several mistakes along the way — like providing journalist Roger Parloff inaccurate information for his 2014 Fortune magazine cover story — Downey argued that her statements about the capabilities of Theranos’s devices were aspirational.

“You know what Ms. Holmes did in her life. You know that she left school. She gave up a college education that people would give their right arm for,” he told the jury. “Why? Because she believed she was building a technology that would change the world.”

Bostic took aim at several of Holmes’ team’s arguments in his rebuttal Friday afternoon. For instance, he noted that investors, board members, and journalists left conversations with Holmes with the understanding that she was talking about Theranos’s present-day capabilities when she led them to believe that the company’s devices were being actively used by the military and that they could run hundreds of tests on a few drops of blood from a finger stick.

"A lie is a lie at the moment that it’s made,” Bostic said. “It does not matter whether Ms. Holmes had the intent to make the lie true or to avoid being found out.”

Jurors have been instructed not to be swayed by sympathy and to consider all of the evidence while keeping in mind that it's up to them to determine how much weight to give each witness’s testimony or trial exhibit.

Birnholz, who previously prosecuted fraud cases for the US attorney’s office in Los Angeles, said that while Holmes’ testimony will likely be top of mind for jurors, they may find that her statements about abuse are not central to the case.

“Her credibility is absolutely essential … and if the jury believes her, then they likely won't convict,” Birnholz said. “But I think it boils down more to what she was saying to investors, what she knew at the time, what her behavior was while she was running that company, how involved was she.”

Robert Weisberg, a criminal law professor at Stanford, said the jury might have a hard time squaring the evidence with the different personas Holmes presented, namely that of a “romantic innovator” who was totally in control and a person who didn’t have agency due to an abusive partner. That dilemma could help or hurt her in the end, he said.

“She was an excellent performer [as a witness], but the script she had to work with was deeply flawed,” Weisberg said.