They know that hackers will be back in 2020.

They know that presidential campaigns, which initially operate for weeks and months via personal email accounts and shared links to Google Docs before they begin to resemble full-scale political machines, are most vulnerable to the threat in their early stages.

And they know that the task ahead of them — ensuring the digital security of a field of Democratic presidential campaigns that will vary wildly in degrees of size, resources, and professional infrastructure — presents an urgent challenge that begins now.

Officials at the Democratic National Committee, the arm of the party that oversees the nominating process every four years, believe they have the tools to help candidates guard against the foreign actors that upended the 2016 election. A few simple steps, they say, can instill a strong culture of cybersecurity from the outset. But over the last month, as announcements rolled in from Elizabeth Warren, Julián Castro, and Kamala Harris, DNC officials held off on contacting campaigns directly about their security practices.

They’re bound by another concern: avoiding the appearance of partiality.

In the years since 2016, when emails stolen by Russian hackers showed that party officials unfairly favored Hillary Clinton over Bernie Sanders during the Democratic primary, the DNC has worked to project a commitment to fairness and transparency. Under Tom Perez, a former labor secretary who took the helm as chair two years ago, the self-described “New DNC” reduced the influence of superdelegates, expanded the schedule for primary debates, and instituted a strict “neutrality” policy barring staffers from expressing a preference for one Democratic candidate over another in 2020.

For the DNC’s cybersecurity team, the impartiality rules have set hard parameters around how they are able to “raise the alarm” for campaigns about cybersecurity.

“We’ve been trying to push as hard as we can to try to catch their attention,” said Raffi Krikorian, the party’s chief technology officer. “So they start reaching out to us.”

“We’re not reaching out directly,” a DNC official added, “because that could show partiality if people aren’t getting the same attention. Hopefully we can send up the flare.”

To do that, the DNC is releasing a best-practices checklist alongside a 10-minute informational video. Both, they hope, will be enough to spur candidates and potential candidates to get in touch with Krikorian and his chief security officer, Bob Lord.

The video presentation — a series of plainly designed blue graphite slides — outlines basic digital security measures like password managers, two-step verification, and secure HTTPS browsing. For 10 minutes and 29 seconds, Lord, a former security officer at Yahoo who joined the DNC last year, narrates the video in a soft, at times dry monotone.

“Did you guys see my movie?” Lord said at the start of a recent interview.

“Honest feedback — how horrible was it? I was wondering how horrible it was,” he laughed. “There are things we can do in the future to make it a little more engaging. There’s only so much charm you can put into that.”

Krikorian and Lord both said they didn’t feel hamstrung by the neutrality rules. But both officials, who were new to politics when they joined the DNC to overhaul its tech practices after the 2016 election, have said that enforcing a cybersecurity “culture change” across the electoral ecosystem has been a particular challenge.

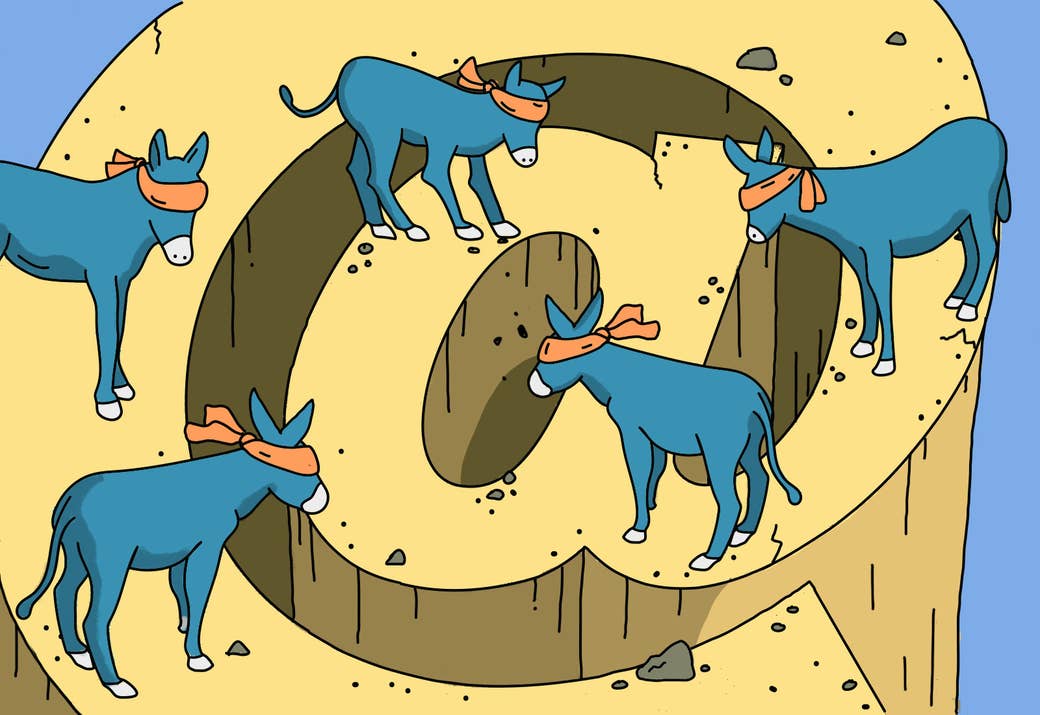

Security officials like to say that your organization “is only as strong as your weakest link.” For presidential candidates, that universe spans a shifting web of staffers, consultants, and volunteers — both inside and outside the official structure of the campaign itself, all communicating daily, each with their own entrenched habits.

“You have kids who are used to using the internet a certain way, and then you have the 60-year-old consultants who are still using the same AOL account,” as one veteran operative put it.

Before 2016, cybersecurity was hardly a priority for the political world. (During Bernie Sanders’ presidential bid, for instance, the campaign allocated just one staffer to manage IT in the Burlington headquarters, leaving state teams across the country to handle their own tech needs.)

Even ahead of the midterm elections in 2018, as the intelligence community braced for more activity from foreign hackers, Democrats struggled to achieve a more systemic “culture change” around digital security.

A plan by the major Democratic Party committees to shift their operations from email to Wickr, an encrypted workplace messaging software, faltered throughout the election cycle. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, known as the DCCC, asked its staff to use Wickr to communicate internally and with operatives working on a select group of high-profile House races, but the practice didn’t stick with any consistency, two officials who work with the DCCC said. (One noted that the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee had more success with Wickr.)

Efforts by the government agencies that investigated the 2016 hacks have been similarly spotty. Last fall, one month before Election Day, the FBI’s Washington field office invited an array of political operatives to participate in a webinar on “cyber hygiene tips” — part of an initiative for campaigns called “Protected Voice,” according to a copy of the invitation. The webinar, scheduled just weeks before the end of the election cycle, was eventually postponed.

For newly formed presidential campaigns, cybersecurity can easily fall to the bottom of the list. One major candidate recently shared a behind-the-scenes video in which a Wi-Fi login and password could be seen on a whiteboard in the background. During the launch of another prominent campaign, senior staffers managed the rollout from their own personal Gmail accounts.

“One of the things that concerns me is there may be opportunity for adversaries to attack long before someone has announced formally their candidacy,” said Lord, the DNC security officer. “So when I talk to people about why are we working on it now, and they say 2020 is so far away — it’s not that far away. I want to make sure candidates understand that they’re a target today, and they need to take appropriate action today.”

After 2016, the political risks are obvious. The Russian military intelligence agency that broke into the DNC in March 2016, the GRU, leaked the emails it found. That move broke something of a mutual agreement between the world’s major cyberpowers: You can hack pretty much anybody to spy on them, but you’re supposed to keep that information classified.

That’s why it mostly went unnoticed that an entirely different Russian intelligence agency — experts are divided on whether it’s the FSB, SVR, or some combination of the two — had actually already hacked the same DNC servers in July 2015, where they stayed for almost a year. Unlike the GRU, those hackers have never been the target of a Mueller indictment or condemned by US senators or intelligence officials, because they simply did what government hackers around the world are supposed to do: sit quietly and gather intelligence.

Last April, four senior Republican officials managing the national party’s House races were hacked by a sophisticated, unnamed actor, the party has admitted.

But that appears to fall under traditional espionage. No files from that hack have been publicly leaked. In December, US Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats compiled a classified report that there weren’t any major hacking operations designed to influence the election, though Russia, as well as China and Iran, had engaged in covert social media campaigns to sway Americans.

One person familiar with the report told BuzzFeed News that the US intelligence community concluded that it simply wasn’t worth foreign countries’ investment to sink real resources into any of the individual House and Senate races.

Foreign governments, the person said, were likely waiting for the 2020 presidential election.

That danger applies to the Republican Party, as well. The party likely won't have to deal with a similar set of unwieldy primary campaigns — while there could still be challengers, Trump is likely the party’s 2020 candidate.

Because of that, there’s less of a chance that hackers will be able to exploit the low-hanging fruit of breaking into a formidable Republican campaign before it gets off the ground. A GOP official said that the party does train new employees in cybersecurity basics, like how to identify a phishing email and set up two-factor authentication, but declined to share specifics about the party’s cybersecurity.

But Trump is in no way immune to hackers. The US president is by definition one of the top spy targets in the world, and even US intelligence reportedly claims that Chinese and Russian spies have listened to calls he insists on making on an unsecured phone.

In a large and scattered Democratic field, where DNC officials will be closely tracking their level of communication with each campaign, Krikorian and Lord will be up against their own challenges.

“It’s important for us to be impartial and fair to all the candidates — and to be able to demonstrate that,” said Lord. “We will be working with them over time. Exactly how, we’re still trying to work out. But one of Tom Perez’s goals — and he says this many times internally — is to give everybody a fair shot.” ●