DHAKA, Bangladesh — Sitting outside a tea shop in Dhaka on a recent evening, Baki Billah, a soft-spoken 36-year-old blogger, glanced from table to table to see if anyone was watching him. “Most of the time now, I stay at home,” he said.

In February, his friend and fellow blogger Avijit Roy, a U.S. citizen of Bangladeshi origin, was hacked to death by Islamist extremists a few blocks away. Roy and his wife were riding home from a book fair when men pulled them out of their rickshaw. Roy was slashed three times on the side of his head. His wife, who survived, was left covered in blood.

Since the start of the year, Islamist fundamentalists have killed at least four secular bloggers in Bangladesh. They have also issued death threats to other bloggers. Dozens more have been named on "hit lists" circulated by extremist groups feared to be gaining ground. So, Billah has been taking different routes to work. Some of his friends have even bought guard dogs.

Since the murders started, many have left the country, or stopped writing. “Everybody got scared: What should I write? What should I not?” he said.

Even as bloggers like Billah continue to battle extremism online, a new series of targeted murders — including the bombings this past weekend in Dhaka — has threatened to upset Bangladesh’s delicate balance between religion and secularism.

Details were emerging Saturday of another attack on a publisher and two writers at a publishing house in Dhaka. Three of them were rushed to hospital with stab wounds, but details of their conditions were not immediately available. Local media identified one of the victims as Ahmedur Rashid Tutul, a close friend of slain blogger Avijit Roy. In a separate incident on Saturday, Dhaka Tribune reported that Faisal Arefin Dipan, the publisher of Roy's book, was also slaughtered to death.

Last week, three bombs ripped through Dhaka's old quarter during a procession marking the Shiite holiday of Ashura. A 14-year-old boy was killed and more than 100 wounded. Another man died in hospital on Thursday. It's the first time that Shiite Muslims have been targeted in Bangladesh.

The attack, which ISIS claimed responsibility for, comes almost exactly a month after a string of attacks on foreign nationals.

On Sept. 28, an Italian aid worker was shot dead while jogging in the diplomatic area of Dhaka. A few days later, a Japanese man was killed in Rangpur district, in northern Bangladesh. Groups affiliated with ISIS claimed responsibility for both attacks, saying “citizens of crusader nations” would not be safe in Muslim lands.

Dhaka has responded with panic. Western embassies have warned of further threats to foreigners. U.S. diplomats have been banned from attending gatherings at international hotels. Most recently, the Australian cricket team pulled out of a planned tour.

While the Bangladeshi government has sought to play down international terror links, experts on the country’s politics say the string of killings indicates a growing extremist threat.

“These attacks on foreign nationals are really ominous and disconcerting, to say the least,” Ali Riaz, a Bangladesh-born political scientist and writer, said in an email.

“We have been witnessing the deterioration of law and order and regrouping of local militant groups for quite some time. These incidents have demonstrated that it has reached a serious level.”

In recent years, Islamist militancy has been relatively well-contained in Bangladesh, the world’s third-largest Muslim-majority nation. Between 2009 and 2013, the government detained hundreds of militant leaders and their foot soldiers, even executing some of them.

In fact, Bangladesh’s anti-terrorism efforts have been seen as so effective that the U.S. State Department has released reports congratulating the government on its efforts. But security analysts say growing intolerance on both sides of the political divide has failed to stamp out extremism, instead pushing fringe organizations to the fore.

“It is difficult to pigeonhole the group that the perpetrators belong to but the ideological narrative is clear, which is both violently anti-secular and anti-Western,” said Saijan M. Gohel, international security director for the Asia-Pacific Foundation, in an email.

The overcrowded list of extremist entities in Bangladesh includes al-Qaeda in the Indian Sub-Continent, which was launched last year by the group’s new leader Ayman al-Zawahiri and has claimed responsibility for some of the bloggers’ murders and identified Bangladesh as a major center for its activities.

And, despite the government’s insistence that ISIS doesn’t exist in Bangladesh, police this year detained several suspected sympathizers.

“ISIS is as much a brand as it is a terrorist group,” said Gohel. “In the last 15 months, there have been a number of lone-wolf plots globally orchestrated by people who have no direct connection to ISIS but are bonded by the ideology and doctrine.”

The once-little-known local outfit Ansarullah Bangla Team (ABT), which is now linked to the killing of the bloggers, is reported to have ties to both ISIS and al-Qaeda.

Last week, ABT sent threatening emails to news outlets in Dhaka instructing editors to fire their female staffers — under some strict interpretations of Islam, women are not allowed to work — and forbid reporting on atheist bloggers.

The roots of Bangladesh’s current crisis can be traced back to 1971 as millions of people celebrated the end of the bloody Liberation War with Pakistan and the independence of a secular democratic nation that accommodated a moderate strain of Islam with a rich Bengali culture.

Over the decades that followed, power shifted between the secular Awami League, led by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, and the center-right Bangladesh National Party (BNP), which allied with the Jamaat-e-Islami, the country’s largest Islamic party.

When Jamaat became part of the former coalition government led by the BNP from 2001 until 2006, it was accused of turning a blind eye to terrorist activities. “This created the opening for the extremist narrative to function and proliferate in Bangladesh,” said Gohel.

"I never thought, when I started writing the blog, that I would be in this kind of situation."

At the same time, the country was grappling with the increasing popularity of austere Salafi Islam, an ultraconservative form of the religion whose followers believe in Sharia law and a unified Islamic state.

Tensions came to a head during the 2013 Shahbag Movement, protests led by secular writers and activists that called for the execution of 1971 pro-Pakistani militants accused of war crimes.

The accused included key members of Jamaat.

Islamists led violent counter protests, demanding the death penalty for bloggers and ransacking businesses belonging to Hindus, who make up 8.5% of the population.

“We were all in fear in my house,” said one Hindu student from the oldest part of Dhaka, who didn’t want to reveal his identity, fearing his safety.

The riots prompted his uncle to move to India.

At the height of the protests in February that year, the threats against bloggers began in earnest.

“I never thought, when I started writing the blog, that I would be in this kind of situation,” said Parvez Alam, another blogger who has been named on the hit list.

Instead of coming out in support of secular voices, Prime Minister Hasina prosecuted them. By the end of April 2013, four bloggers had been arrested under a controversial section of Bangladesh’s Information and Communication Technology Act that criminalizes “pushing fake, obscene or defaming information in electronic form.”

The national police chief warned other writers not to “cross the line.”

“The government is bound to protect all its citizens — that is not something that is happening in Bangladesh,” Parvez said.

While the opposition has created space for extremism through collaborating with militant groups, the government has done the same, some analysts say, by pursuing a contradictory line, capitulating to Islamist demands over the bloggers while cracking down on mainstream political dissent. In February, a Crisis Group report warned that the squeeze on mainstream opposition had pushed the ruling party’s opponents toward more extreme organizations.

“Growing use of extremist rhetoric and acrimonious mainstream politics all contributed to it, as much as the external developments such as the rise of ISIS,” said Riaz.

In recent years, Prime Minister Hasina’s government has become increasingly authoritarian. In August 2013, it banned Jamaat from participating in elections and has since threatened to ban the BNP, which is led by Khaleda Zia.

The feud between these two women, who both owe their positions of power to their rival fathers, casts a toxic shadow over Bangladeshi politics. Hasina represents secularism while Zia sides with Islamic parties. Many people are sick of both of them.

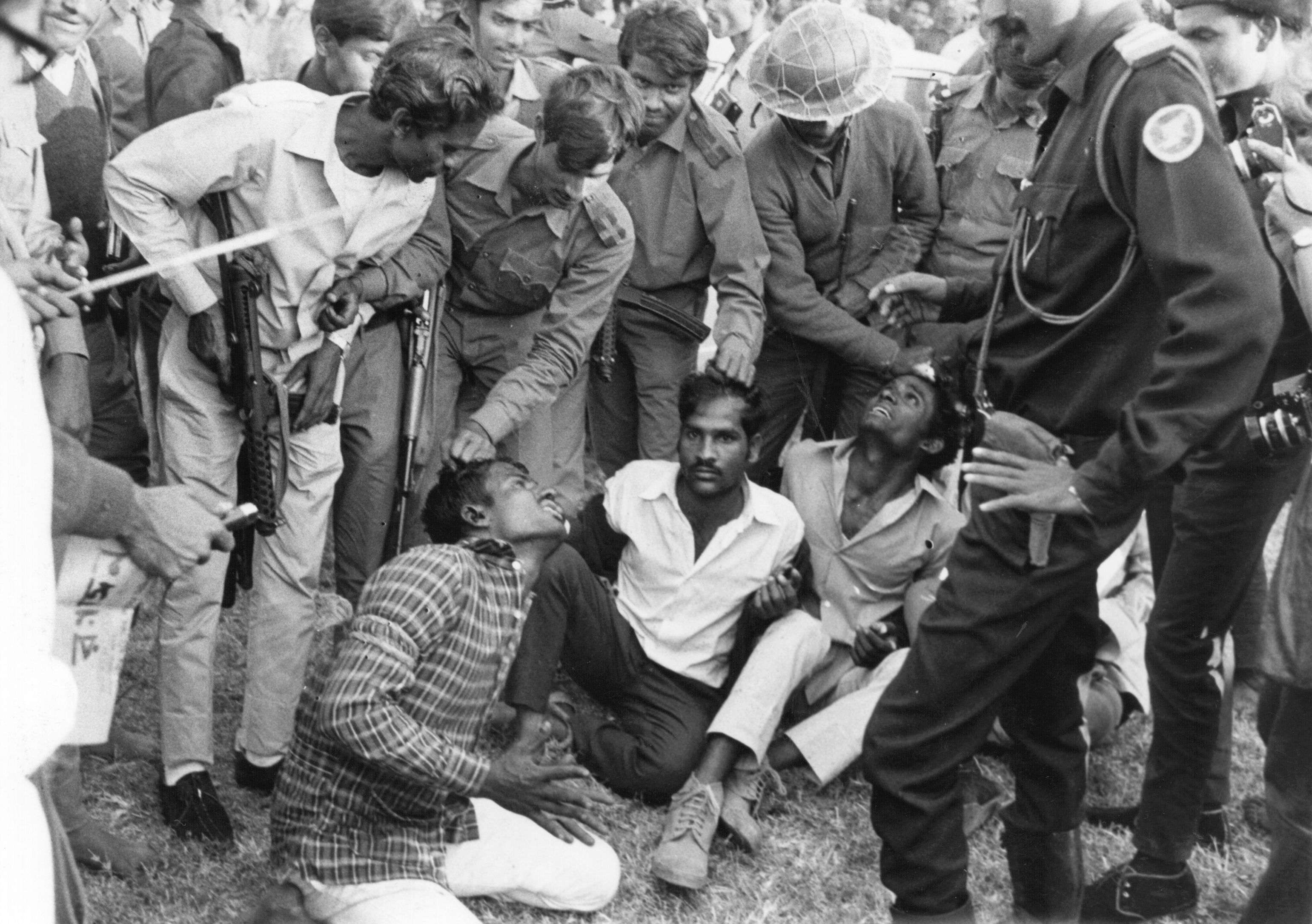

While taking flak for failing to stand up for secular bloggers, the Awami League has not been afraid to wield extreme force against political opponents, deploying the Rapid Action Battalion, Bangladesh’s elite but controversial counterterrorism unit, to crush dissent. The battalion, which has received endorsement and support from the United States, has been accused of the extrajudicial killings and forced disappearances of opposition activists and political opponents of sitting ruling party MPs.

“What we are observing in Bangladesh is a combination of extortion, brutality and intentional disregard of law all under the pretext of a political arrest,” the son of a prominent politician who was detained multiple times without charge told the New York Times last year.

Shahidul Alam, a photojournalist and blogger who has documented the work of the battalion, believes the ruling party has contributed to a climate of impunity.

“I think what we are looking at is a general upscaling of action against dissent of any form,” he said in a phone interview. “When that happens, that creates an environment that anyone outside can take advantage of.”

Shah Ali Farhad, assistant secretary of Awami League’s central sub-committee, insisted that the government had done enough to combat militancy.

“Terrorism and extremism at today’s date are global issues,” he said in an email. “All countries are at risk and, hence, none can avoid or neglect. Bangladesh is no different.”

UPDATE

This article has been updated after removing some information about a writer, which they feared would put their life at risk.