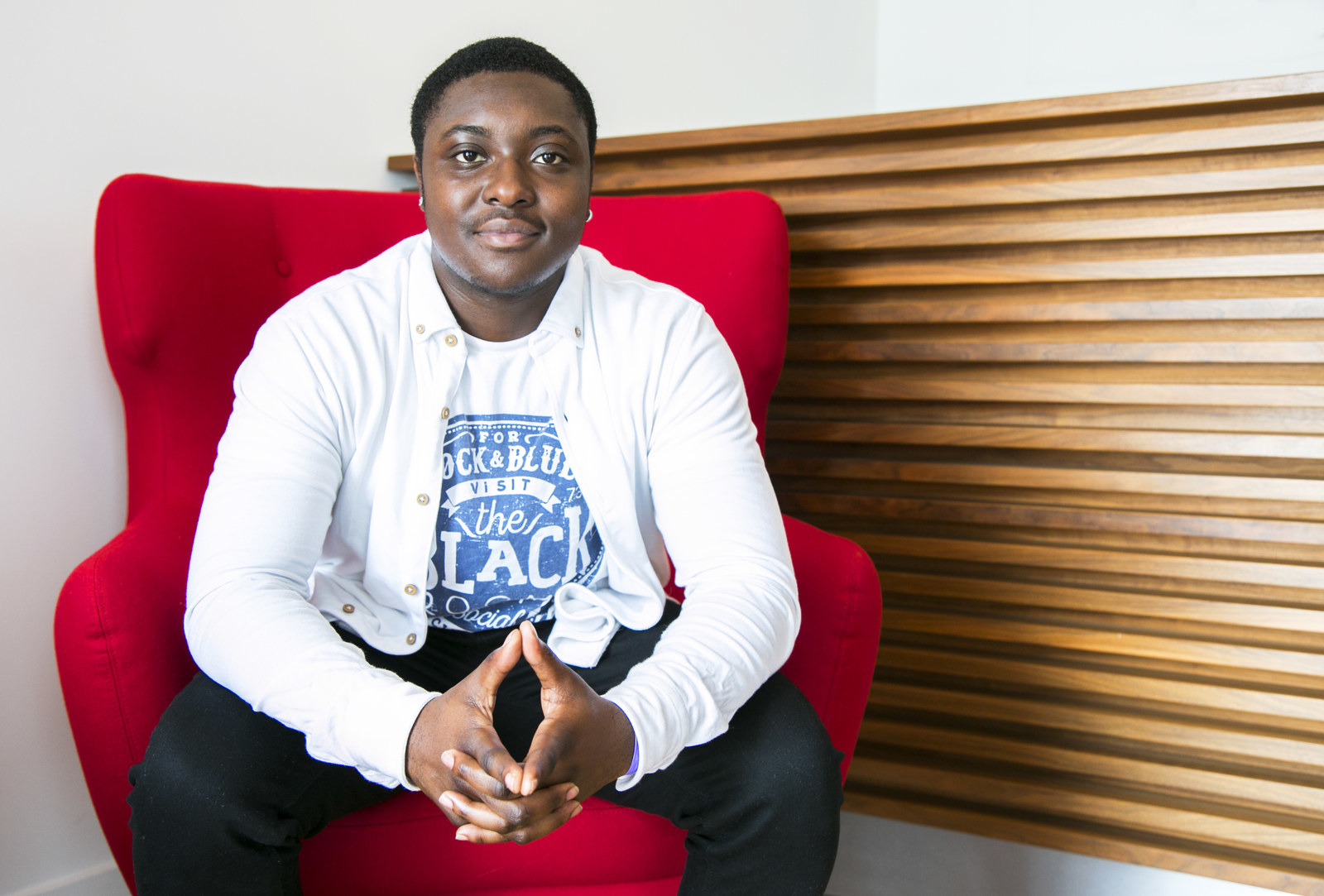

“As a teenager, when I was coming out, I said to my mum, ‘Either you want a dead daughter or a happy son.'” We are just a few minutes into the interview. Tyler Luke Cunningham, the new star of the much-fêted BBC sitcom Boy Meets Girl – the first to focus on a trans character – is talking in a sparse, echoing meeting room in the offices of the show’s production company. His press officer, who has never heard what he's about to reveal, sits frozen and silent.

“I couldn’t see a future,” says Cunningham.

As the actor begins describing what he had to do to convince those around him that being transgender was not a phase but life-and-death, he does so with such a plain, unsentimental delivery it takes a while to realise why.

Transitioning to become the man that he is – taking hormones, telling his family and friends – was not, it transpires, the hardest, nor the most extraordinary of his experiences.

His life was also not the only one he had to save.

That story comes later, however, once he’s rattled through his own. The speed of his delivery prevents any lingering on painful memories, but also suggests something else: an acute sense of urgency.

There are not many 20-year-olds, perhaps none other, who have both embarked on the transition process and also forged a successful acting career, snatching a part in the second series of a primetime sitcom. His character in Boy Meets Girl is Charlie, a tough/sweet friend to Judy, the lead, played by Rebecca Root. He did not expect to win the part – he'd never seen the show, he says – and so was "shocked but really happy".

Rebecca Root (left) and Tyler Luke Cunningham in Boy Meets Girl.

The shock was not only down to the slim chance for any actor of being cast in a hit show. Just five years ago, aged 15, everything was turmoil.

“There were a lot of problems in my life at that point,” says Cunningham. “Everything was a blur in my head, foggy, I wasn’t sure what was going on. I had a very ill sister and a mum who wasn’t very well herself, who was having to deal with my ill sister and deal with my bad behaviour as a result of me not knowing what was going on in my head.”

His sister Keyleigh, who is seven years older, had been diagnosed with aplastic anaemia, a rare, life-threatening blood disease in which red and white blood cells as well as platelets stop being produced properly, causing a dangerous deficiency. His mother has lupus, an incurable disease in which the body’s own immune system attacks healthy cells.

Cunningham, therefore, was trying desperately to manage what was happening both in his family and in himself.

“I didn’t know who I was,” he says, trying to explain what that meant. “I remember looking into my future in my head and I could never see my face. I can understand why some young trans people don’t feel that there’s a way out.”

He adds, swiftly, “They need to know that there is.”

It took Cunningham a while to realise this himself. “I was very angry and confused and I wasn’t the easiest person to speak to,” he says. The problems did not only manifest internally, but also to such an extent externally as to trigger an explosion in his home life.

“I went into care,” he says, in the middle of a sentence, as if it is worthy only of passing mention. He was still only 15. What happened?

“My mum couldn’t deal with my bad behaviour anymore. I was completely acting out. She was under a lot of pressure, looking after an ill daughter. She just couldn’t cope – understandably. It made sense for her.”

As an adult himself now it might well be understandable, but at the time?

“It seemed like my mum was doing the worst thing in the world.” Cunningham lets out a small laugh – the same laugh as when he mentioned the bad behaviour that proved so difficult for his mother. It is more of a quick release of breath, as if momentarily unscrewing the nozzle on a pumped bicycle tyre.

He was in care for 11 months. It proved pivotal.

“If I didn’t get away from my family at that point I may never have realised who I was,” he says. Unbeknown to his mother, the space and time apart was exactly what Cunningham needed. “I can only thank her for it, in a way. It was the right thing to do.”

On his return to the family home in London, two further transformative events took place. First, now aged 16, he started to tell those around him who he was.

“There’s always going to be that shock factor when you come out as trans – it’s still quite taboo – but now that I look back, they did get over it quite quickly,” he says, avoiding spelling out how instrumental he must have been in moulding the reactions. “There were people saying, ‘Are you sure it’s not this or that?’ I had to be sure to make everybody else sure. I had to make people understand that I was being totally serious about this.”

And when he told his mother, making it clear that there was one option: transition or die, she quickly accepted what he was saying. “I think it sunk in quite well,” he says, with knowing understatement.

At Cunningham's drama college (Platinum Performing Arts school in north London) which he attended for five years, there were, he says, some obstacles to ensuring people used the correct pronoun. But for Cunningham it proved another vital escape, an “outlet” for expression when he needed it most, both “pre-transition and while I was transitioning”.

“All the people around me are very accepting – black, white, man, woman – and those who aren’t just aren’t in my life,” he says.

There was someone else who supported him throughout: his girlfriend, Lovelle.

“I’ve been with her just over two years,” he says. “She just took me for who I wanted to be; she’s loved me from before [transitioning]. I’ve grown into the man I’ve wanted to be and she’s wanted me to become as well. She gave me courage and strength to go about my daily life, because I know there’s someone there who loves me.”

When they first met aged 17, when Cunningham was living as a man but not yet taking hormones, there was a much more immediate issue to confront, the one that now seems to dwarf everything.

“My sister’s body was shutting down,” he says flatly. The disease had been causing terrible damage for a while: bleeding from her mouth, bruising so quickly that even a touch would leave a mark. Keyleigh had to move back home to be looked after, giving up her job as a pastry chef in a top London hotel, but her condition only declined.

“Patients require regular blood transfusions to keep their blood levels up, platelet transfusions to avoid bleeding and bruises, and they are prone to life-threatening infections due to their low white cell count,” says Olga Nikolajeva, medical officer at the Anthony Nolan Trust, a leukaemia and bone barrow transplant charity. “Patients with aplastic anaemia often develop blood cancers later on in life if they don’t receive a bone marrow or stem cell transplant.”

Keyleigh (left) and Cunningham with his family.

And although aplastic anaemia is not a form of cancer, it is sometimes treated like it, says Cunningham. So his sister underwent chemotherapy and radiotherapy, while also having her eggs harvested so if she survived she had a chance of becoming a mother.

The treatment did not work. “She was on life support,” says Cunningham. “I remember walking into hospital, seeing her on life support for the first time, and bursting into tears. She just wasn’t there. She almost died twice. Her pupils weren’t dilating, all her organs were shutting down. They [the doctors] said, ‘She’s about to go.'”

There was only one option left: a bone marrow transplant. The hospital began a frantic search but there was an acute shortage of potential donors.

“Only 1.7% of people in the UK are registered as donors,” says Nikolajeva. In particular, she says, there is a lack of “young men and people from black, Asian, and ethnic minority backgrounds”.

Having failed to find an anonymous donor from the register, the hospital instead considered Cunningham’s family. His parents were unable to donate, and so it fell to him.

“I thought, OK, I just have to go through with it,” he says. The process began with two injections twice a day for four days to spark in Cunningham an overproduction of bone marrow.

“I then had to go into hospital for two days, as a day patient, get dripped up, with about four different drips in my arms. Then they used a dialysis machine to take the bone marrow from my blood before it was given to my sister.”

But after the transplant, Keyleigh's condition worsened dramatically.

“She almost died again,” says Cunningham. “Because my bone marrow was a foreign body to her, her body went into crisis and she was back on life support for a while.”

Eventually, however, she pulled through. The transplant began to work.

Cunningham was there the day the doctors began to wake her up. Still with tubes down her throat, he says, Keyleigh could not speak. And so Cunningham devised a way to communicate with her.

“I got some paper towels and wrote every letter of the alphabet on them with a felt-tip pen,” he says. “I went along the letters and said, ‘Blink once if it’s yes and twice if it’s a no.'” He hoped that this way he could decipher what she wanted to say.

“In a nutshell,” he says with a smile, “she wanted her handbag and her mobile. That was it.”

Keyleigh came out of hospital to begin the process of recovery. But while still receiving treatment from home, it wasn’t long before she felt ill again.

“She went for a checkup, they checked her back thinking it was her liver, they turned her over, and the woman [doctor] said, ‘How far gone are you?’ And Keyleigh was like, ‘What?’ And that was it. That’s how she found out she was pregnant." It had happened naturally, he says, without even the eggs being reinseminated.

Cunningham beams – joy and gratitude flickering across his face. "And now I have a beautiful little nephew.” Blake is 2 and healthy.

“I consider him a piece of me,” says Cunningham. “Because if my bone marrow helped her get better then he’s the end product of that, in a way. He’s an angel.”

Although Keyleigh is still not back to full health and uses a wheelchair at times, she and Cunningham grasp every opportunity to be together. “She loves music, so we’re constantly going to concerts together," he says. "We’re going to Vegas for my 21st birthday in November. She’s an inspiration for me."

The sweep of her illness, and the timing of it, transformed their relationship, he says.

"It’s really weird: We were close as children, then fiery at each other as teenage girls – [as we were] at the time – but then seeing her ill flipped it for me, because I was just like, oh my god, that’s my sister. It was really hard. So being able to transition has also made us grow closer. She’s gone through something, I’ve gone through something, and we’ve come out the other end together.”

They’re also now involved with the African-Caribbean Leukaemia Trust, which, among other activities, encourages people from ethnic minorities to join the bone marrow donor register.

The bond between Cunningham and his sister, along with that with his girlfriend, seems crucial for him in withstanding some of the transphobia and racism in everyday life. Given such an intersection of race and gender, it might seem pertinent to ask Cunningham what he has noticed in the change in people’s perception of him, from being someone was once perceived to be a young black woman and now a young black man. But, he says, it's impossible to isolate these factors into a before-and-after transition split.

“As a young female I was very angry, and before hormones I wasn’t comfortable speaking to people, whereas now now I’m so much more vocal with my opinions and I’ve become a better person. So I feel like other people have seen that as well. Regardless of the fact I’ve gone from one thing to another, they all know I’m a better version of the person I was.”

But as an actor, brutal and sometimes discriminatory casting processes remain an issue.

“I’ve been turned down for a role – not that long ago – because it was for a cis [non-trans] male part,” says Cunningham, without divulging what the role was. “My agent said, ‘Well, he looks like a bloke, sounds like a bloke, walks like a bloke, so why can’t he have the part?’ And they said, ‘Because he’s trans.’ It’s ridiculous. Unless it’s a full-frontal nudity scene where I might not feel as comfortable, what’s the problem?”

Cunningham wants to see more trans people enter the performing arts so there is a wider pool of acting talent from which casting agents can draw.

“It would be great too if there were more trans men on TV to give trans men who are transitioning someone to look up to,” he says. “Hopefully I can be a voice for some trans people and for people who don’t know they’re trans yet, to help some people realise that’s who they are.”

As he smiles again, an elbow bent around the top of the chair, bicep curling in, a picture of someone at ease with himself, the final question is unavoidable. What would Cunningham have thought aged 15, if he could have seen what his life would become?

He stops for a moment – a rare pause to allow himself to relive that time.

“I wouldn’t have believed it.”

Boy Meets Girl is on BBC2 at 10pm every Wednesday.