On August 5, 2015, a crew of EPA workers and contractors surveying the abandoned Gold King Mine in Colorado dislodged a plug at the site, letting 3 million gallons of trapped water — containing arsenic, mercury, lead, and more — wash into a tributary of the Animas River.

The river carried the sludge southwest, and within days the Animas and San Juan rivers turned an alarming shade of yellow. After two weeks, the EPA announced an investigation into the causes of the event and the agency’s response to it.

Downstream in New Mexico, in the Navajo community of Shiprock, farmers use river water to irrigate corn and cantaloupe, and raise sheep and goats. The spill caught farmers in the middle of their growing season.

Navajo Nation community health representative Mae-Gilene Begay mobilized a crew to warn residents to steer clear of the river water. “A lot of them were concerned because they go fishing in the river either for recreation for livestock or for farming,” she told BuzzFeed News.

The community closed the irrigation canals for eight months, until April 2016. A few months later, the Navajo Nation sued the EPA and mine owners and operators, claiming that the parties' negligence caused an accident they should have foreseen and prevented.

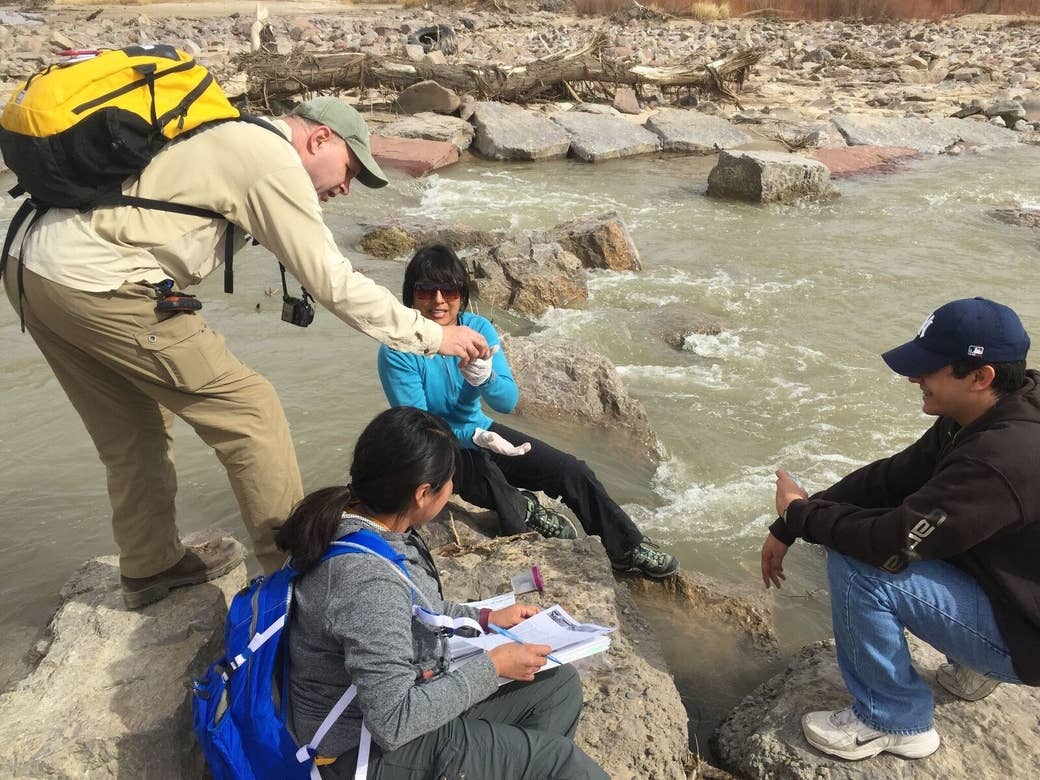

Over the last year and a half, a group of scientists from the University of Arizona has been working to help the Navajo understand the impact of the spill, by presenting data about contaminant levels to the community so that they feel empowered to decide whether to start using river water again.

Led by Karletta Chief, a hydrologist, and Paloma Beamer, professor of environmental health, the team has collected about 1,000 environmental samples: water and soil from the river and irrigation canals, water from wells and conduits, and samples of blood, urine, and drinking water from 60 homes in three communities.

On Wednesday afternoon, the researchers returned to Shiprock Chapter in New Mexico to share their preliminary findings. And it’s good news, at least for now: lead and arsenic levels in the water are within the levels defined as drinkable by the EPA. In all but four of the water samples, the lead levels were also below the guidelines that the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration has deemed fit for aquatic life.

Some Navajo are relieved by the data, though they are slow to fully trust. “There is justified apprehension by farmers on whether to plant this year considering the questionable state of the river,” Duane Chili Yazzie, Shiprock Chapter President, said at Wednesday's event, according to an email he sent to BuzzFeed News. “This apprehension is only partly relieved by all the studies that purportedly show the water to be safe for irrigation.”

The findings are consistent with what federal and tribal environmental agencies have shown, noted UA's Beamer. When the project is complete, this new analysis aims to be a more comprehensive risk assessment than those done before.

“It’s really a time to present all the data that we have to date back to the community,” Beamer told BuzzFeed News.

The scientists did find one series of abnormal readings: a pattern of high manganese levels.

About a quarter of the samples collected from canals had manganese levels above the EPA’s level of 50 parts per billion. About half the samples from wells in the winter were also above this limit, along with a few river samples collected during the spring. (The EPA classifies this metal as a secondary contaminant, which means it is associated with bad taste and odors rather than health effects.)

The scientists don’t think the manganese came from the mine spill, however.

“The highest concentrations we measured were in the wells, which are not likely to be affected by the spill and are more a function of the natural geology in the area,” Beamer said.

Later this year, the researchers are planning to report additional data from their study, related to the soil surrounding the river and irrigation canals. These analyses will show whether there are toxic metals remnant from the spill. Blood and urine samples are also still to be tested.

The team is also compiling a library of all the ways the community uses the river — from ritual drinking of river water during prayer, to picking reeds from the river for weaving baskets, in addition to drinking, bathing, and farming. In later reports, the researchers hope to describe whether and how the spill has changed those habits.

Despite the fact that the EPA reported that the water was safe for agricultural and recreational use, the message did not disseminate through most of the community, Begay said. “I think there’s only a few folks that have heard the EPA’s update.”

In April last year, the Navajo Nation EPA recommended opening the irrigation canals, based on readings taken by the tribal agency and the US EPA through the fall and then in the spring. “But a lot of people still did not irrigate last year and are still concerned this year,” Stephen Austin, senior hydrologist at the Navajo Nation EPA Water Quality Program, told BuzzFeed News.

So for many on the reservation, the evidence presented Wednesday carried more weight than federal reports.

In the weeks after the spill, as the cause became clear, Shiprock residents were immediately concerned about preventing a similar event from recurring, Janene Yazzie, co-founder of the Tó Bei Nihi Dziil (Water is our Strength) collective, a group that works on water issues, told BuzzFeed News. But those concerns were largely ignored by the agency representatives who visited in the weeks and months after the spill.

“How will you protect us from future spills? What can we do to clean up the water before it gets to our crops? [Those] was the questions that were glossed over too easily or too soon by the tribe and federal agencies,” Yazzie said.

Also, presentations from agency representatives were peppered with unfamiliar buzzwords like “background levels,” which confused and further worried many farmers.

When Chief addressed the crowd at community meetings, she often spoke in Navajo. She also decrypted the jargon. For example, Yazzie said, she explained the concept of parts per billion, the accepted metric to measure miniscule levels of metal in water, by comparing the value to a grain of sand in a bag, or in a cup.

“She gave them their power back in terms of being critical, and thinking more deeply about what was being presented to them,” Yazzie, who is collaborating with University of Arizona team, said. “She gave them that tool to understand.”

UPDATE

This story has been updated with comments from Duane Chili Yazzie.