ALEXANDRIA, VA — The US Patent and Trademark Office became a magnet for lawyers, reporters, and analysts Tuesday, who gathered to witness a public chapter in a high-profile patent fight: Who is the inventor of CRISPR, the hottest biotech tool in modern history?

Engulfed in a legal battle for two years, “this is the first public, out-in-the-open procedure that we would have had in this case,” said Jacob Sherkow, a professor at New York University Law School told BuzzFeed News. “It’s also significant because it may be the last oral argument that we may have in this particular case.”

Hearings in front of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board typically feature one or two public audience members. But witnesses for the CRISPR hearing queued more than an hour ahead of proceedings to enter the hearing, and then filled two overflow rooms.

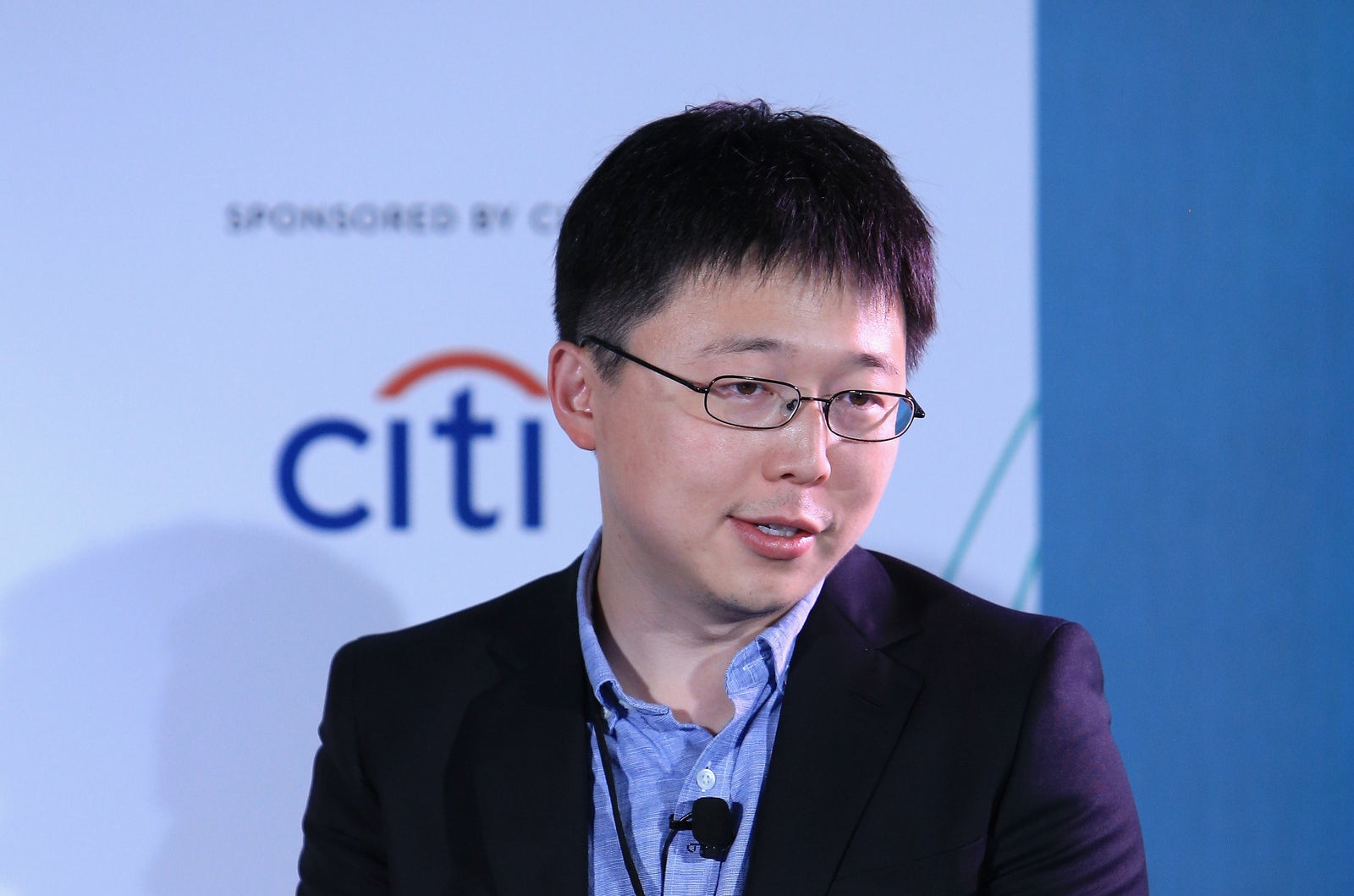

The primary players in the invention dispute are Feng Zhang, a research scientist at the Broad Institute and MIT, and scientists Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, who are represented by University of California at Berkeley.

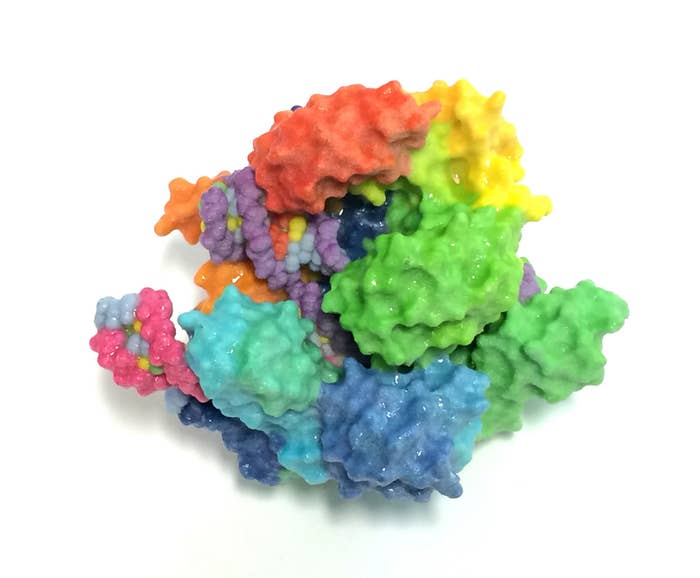

At the heart of the fight is a gene editing mechanism occurring naturally in bacteria that can add or remove precise sequences of DNA from organisms, first identified in the mid-1980s and explained in 2008. The fuss-free, low-cost technology allows tailor-made genes to be slid in and out of cells by scientists, and heralds an era of designer production of biofuels, drugs and other materials. With the patent battle just cresting, more than $600 million has already been poured into biotech companies that are planning to use the technology commercially.

Doudna and Charpentier were the first to file a US patent that demonstrated how the technique could be modified and used in the lab, in 2012. Zhang and team filed a patent application months later, along with a request for a so-called “fast track.” Zhang’s application was reviewed and granted first.

In 2015, the UC Berkeley team filed a challenge to Zhang’s claim, a move known among patent types as an “interference.” Tuesday’s arguments focused in large part on one paper from the UC Berkeley team, published in August 2012 in the journal Science, that describes how the cut-and-paste system works.

The Broad team argued that the UC Berkeley team had not shown how the system would work in eukaryotic cells — non-bacterial cells that include yeasts, and rats, and human cells — where the technology could make the biggest impact. Instead they argued that Zhang’s work rested on a unique and novel insight (it was “non-obvious” in patent law parlance) in operating on eukaryotic cells, and therefore deserved its separate patent status.

“This is the antithesis of something that should have been obvious,” Steven Trybus, of Jenner and Block LLP, said in this comments representing the Broad.

The Broad team’s work, which demonstrated the tool in human and mouse cells in 2013, was an essential addition to the toolset that allowed other researchers to follow in their lead, Trybus added.

On the other side, the UC Berkeley team argued that the pieces were in place in the 2012 paper led by Doudna and Martin Jinek. They argued the next step — demonstrating it in eukaryotic cells — was an obvious, and intended, next step.

“Let’s look at what actually happened after the publication,” Todd Walters, of the firm Buchanan, Ingersoll, and Rooney, who represented UC Berkeley, said. “There were six different groups within six months to move the system … into a eukaryotic environment.”

“There was no special sauce here,” he concluded.

Legal observers, however, suggested that UC Berkeley’s argument faced harder questions from the patent law judges during the hearing, suggesting that Doudna and Charpentier face an uphill battle in overturning the Broad Institute patent.

“It seemed as if questioning towards the UC lawyer was significantly more intense” Sherkow said, at a panel discussion about the hearing hosted at American University Law School Tuesday afternoon.

Robert Cook-Deegan, director of the Center for Genome Ethics, Law & Policy at Duke University agreed. “I sensed a fair amount of skepticism from the judges,” he said, adding that it suggested they may be considering the possibility that the Broad team deserved kudos for demonstrating the technique in eukaryotic cells.