Marlowe Stoudamire devoted his life to making sure that Detroiters reached their full potential.

Stoudamire was an entrepreneur who worked in many fields throughout his career — at a major hospital, as a business consultant, and as a developer of a prize-winning historical exhibition. His driving passion throughout this work, said his friends and colleagues, was to build up the community and promote the talent of black Detroiters.

"He saw you before you saw yourself,” said Eric Thomas. Thomas, who was 11 years younger than Stoudamire, became close to him several years ago and saw him as “in between a father figure, a big brother, and a business partner.” Thomas, who now holds a job as “chief storyteller” on the City of Detroit’s communications team, said Stoudamire was always finding ways to help people like him get ahead. “Marlowe is a champion for young Detroiters, particularly black Detroiters.”

Stoudamire died on March 24 of COVID-19, the Henry Ford Health System confirmed to BuzzFeed News through a spokesperson. He was 43.

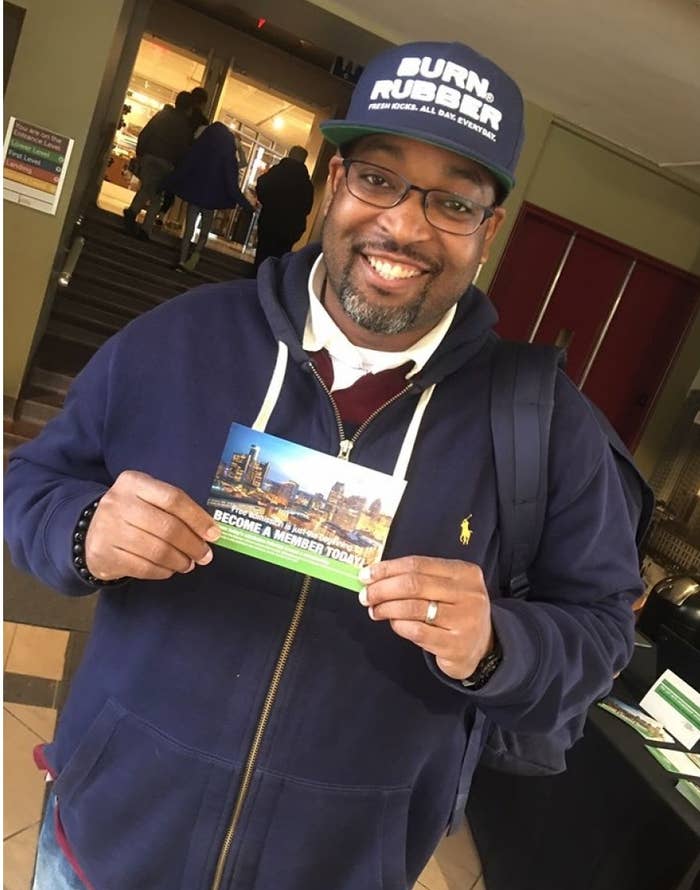

One of Stoudamire’s emblematic project was called Roster Detroit. It began as a project on his Facebook page in February 2019, where he’d write profiles of black Detroiters with big potential. He started the initiative after Amazon reportedly rejected Detroit’s bid to house the company’s new headquarters because it believed the city didn’t have enough talent, according to the Detroit News.

“Marlowe was like, ‘What the hell, man!’” said Brian Bono, who became Stoudamire’s partner on the Roster Detroit project. Stoudamire initially focused on raising the profiles of black men, Bono said, because he wanted to encourage a culture of men lifting each other up. But the project eventually became so broad that they planned to turn it into a business, connecting talented Detroiters with work.

“Right away he was getting DMs from different companies with opportunities around Detroit,” Bono said. “Marlowe’s dream was always about other people. We never talked about making the next Facebook or another app — it was always rooted in helping people.”

Stoudamire grew up in a rough neighborhood on Detroit’s east side and remained devoted to the area even as his career took him all over the world. He was a proud graduate of Detroit’s Cass Technical High School, a magnet high school that helped launch many successful Detroiters, and he stayed in the city for college at Wayne State University. One of his first jobs was building international partnerships for the Henry Ford Health System, and then he became chief of staff at a foundation focused on education in Detroit.

Stoudamire was tapped in 2016 to spearhead a major project by the Detroit Historical Society to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 1967 uprising among black Detroiters against decades of institutional racism. Stoudamire brought essential bridge-building skills to this project, said the Historical Society’s Rebecca Salminen Witt.

The 1967 uprising, which was the largest civil disturbance in 20th century America, was still hard to talk about in an area that remains deeply divided along racial lines. And, Witt said, there was a perception that the Historical Society was a white institution.

“We needed a personality who had the community behind him or her and could kind of bring the community together … [with] the African American community at the center,” Witt said. Stoudamire helped turn their approach to the exhibit “inside out,” Witt said, basing their work on a broad effort to collect more than 500 oral histories of the uprising from a broad cross section of Detroiters. He had a “big-idea energy that was brave and not afraid to try something that we’d never done.”

Stoudamire was involved in many other projects, including advising the Michigan State Police on recruiting minority officers and women, said his business partner, Tatiana Grant. He also was working with the National Hockey League to build community relationships. He had big ambitions for himself and Detroit, said Thomas, the city of Detroit’s chief storyteller.

“The city lost an icon when we lost Marlowe,” Thomas said. His death from COVID-19 “is one of those things that’s not supposed to happen.”

“You could tell he was about to take off,” Thomas said. “He was about to change everything.”