There are few surer signs of the apocalypse than a plague of locusts stretching miles across, turning the sky black and devouring everything in their path.

“They cast a shadow on us, just like when clouds get between us and the scorching sun,” said Shurie Hassan, a Kenyan farmer who watched in horror as the locusts terrified his animals in early January. “I have never seen anything like it before. None of my family members had ever seen insects in such gargantuan numbers.”

The hashtag #locustplague has taken off on Kenyan Twitter in response to the worst outbreak in the country in 70 years. Followers of one celebrity preacher who claims to have prophesied the coming of the insects last April have even flooded social media with calls to repent. Others have simply tweeted Bible verses about plagues as divine punishment.

#LocustPlague No nation can run away from the judgment of God,leaders must first humble themselves and call a national repentance day not interdenominational prayers to be presided by none other than the messenger of righteousness alone to speak to his friend.

But this — of course — is not simply an act of God.

The insects have in fact benefited from human conflicts, and some of their most fertile breeding grounds have been in war zones — in Yemen, Somalia, the Indian-Pakistan border — where fighting between people has complicated fighting against locusts. Their arrival is also partly manmade in another way, according to climate researchers. Locusts need heavy rain to breed in these numbers, and climate change has contributed to many of the downpours that came to the affected regions after years of drought.

“The larger story here is that this is the new normal,” said Rachel Cleetus, policy director of the Union of Concerned Scientists. The same ocean warming trends in the Indian Ocean that created the hot, dry conditions that fueled Australia’s bush fires are also bringing rainfall to East Africa, she added. “We’re all connected.”

One of the Kenyan counties currently battling locusts is Garissa, where around 150 people were killed in a 2015 attack on a university by the Islamist fundamentalist group al-Shabaab, based across the border in Somalia. Al-Shabaab militias are still fighting in Kenya — an attack earlier this month killed four school children — and some roads have been rigged with explosive devices, making it impossible to send locust eradication teams to some affected areas.

“As much as we may want to rush there, we first have to think ... could [our teams] be attacked on the way, or [drive through] an area on the road where IEDs could have been planted,” Abdinoor Ole, who is coordinating locust response for the Garissa county government, said in a phone interview with BuzzFeed News.

Locusts can cause catastrophic devastation to crops, pastureland — even to trees. The swarms in Kenya can consume as much food in a single day as 85 million people — more than three times the population — could eat, according to Keith Cressman, the senior locust forecaster for the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

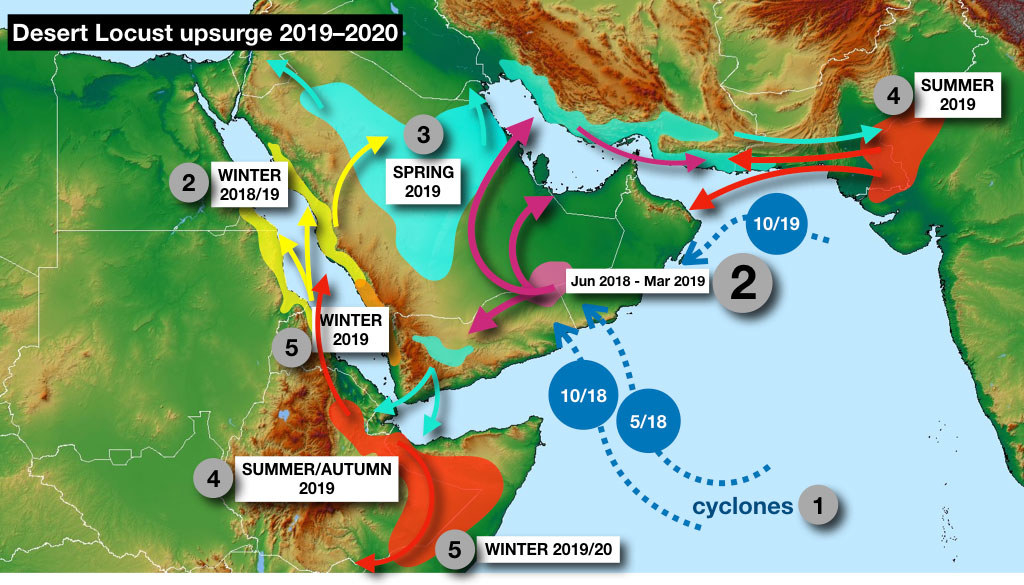

The population of locusts afflicting Kenya first exploded in the arid desert along Saudi Arabia’s southern border with Yemen and Oman known as the “Empty Quarter,” because it is so inhospitable to human life.

Two cyclones hit the area in 2018 — an unusual occurrence — creating an extra-long breeding season for the insects, Cressman said. This allowed their numbers to increase exponentially. But it happened in such a remote place that the locusts were barely noticed by humans until it was too late.

“Nobody knew about it,” Cressman said. “They were increasing about 8,000-fold for those nine months, with no disturbance and no control.”

In the spring of 2019, the locusts took flight, with one group heading north through Saudi Arabia and Iran, joined by other populations from Sudan and Eritrea.

It was an unusually wet year throughout the region, and the locusts arrived in Iran just after floods that Iranian government officials attributed to climate change. The government did not take the locust threat seriously, and Iranian leaders also laid blame on its regional opponent Saudi Arabia for allowing the locusts to breed in the first place.

Kaveh Madani, Iran’s former environment minister, blamed government complacency for not taking necessary action against the locusts in an email to BuzzFeed News. But he added the lack of international cooperation didn’t help.

“This is a transboundary problem and transboundary problem solving is very hard when there is no peace and the countries do not have stable political relationships,” he wrote.

Mohammad H. Emadi, Iran’s ambassador to the FAO, said that US sanctions prevented Iran from getting its hands on pesticides. He added that war and climate change were “twisted phenomena which accelerated each other.”

From Iran, the locusts moved east into India and Pakistan, where tensions between the country were high. They arrived shortly after a February attack by a Pakistani militant group on an Indian military convoy in the disputed region of Kashmir.

This attack made “any collective efforts or even information sharing is extremely difficult,” Cressman said.

Like Iran, the region had suffered drought followed by unusually long rains, creating the perfect conditions for locusts to multiply. This is “very much caused by climate change,” said Pervaiz Amir, director of the Pakistan Water Partnership, an organization coordinating with government agencies to manage water resources.

As one group of locusts were working their way through India, Pakistan, and Iran in 2019, another group had found fertile ground in Yemen, which was, like other places in the region, getting an unusual amount of rain.

The civil war there made it impossible to bring the problem under control, Cressman said. Both the Saudi-funded Yemeni government and the Iran-backed Houthi insurgents said they lacked resources and equipment for large scale efforts to combat locusts, Voice of America reported.

By the summer of 2019, locusts had arrived in the horn of Africa.

This was one of the wettest periods on record in the region, said Chris Funk, who researches precipitation in the region at the Climate Hazards Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

The rain was due in part because the western Indian Ocean off East Africa’s coast had reached its hottest temperature ever recorded.

“I would be extremely unlikely to get sea surface temperatures that warm in a world without climate change,” Funk said. “When the [locusts] got to Somalia, they found an incredibly green, verdant Somalia where they could really just go to town.”

Somalia has a fragile government following years of civil war, and al-Shabaab and other groups are still fighting the internationally recognized government. This made it hard to organize a response, Cressman said.

By the end of December, the insects had wiped out more than 175,000 acres in the country, destroying crops and grazing lands in an area already suffering from food insecurity.

After another round of rainfall in December, the locusts were able to move west into Kenya.

Kenyan officials are bracing for additional waves of locusts over the coming weeks, while the UN is advising neighboring countries including South Sudan and Uganda to be on high alert.

The FAO is pleading with wealthy nations to support extermination efforts to avoid the crisis from spreading further, saying $70 million is urgently required for eradication efforts. Under current weather conditions, the agency predicts the locusts could grow 500 times more numerous by June. Meanwhile, the FAO is also monitoring large populations of locusts that are breeding anew in eight other countries.

In Kenya, Garissa county officials believe they’ll be fighting locusts in the area for the next six months.

“The insects are literally finishing the fodder that is the source of support to our livelihood,” said Hassan, the animal herder. “This is very scary.”

Ali Abdullahi Doll contributed to this story.