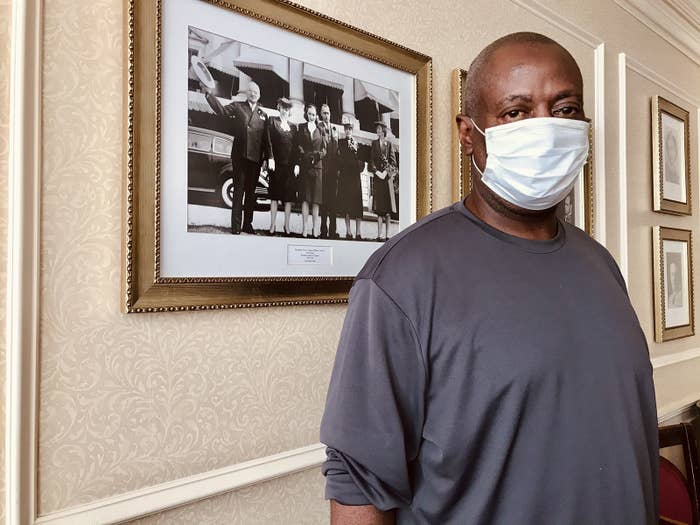

Leon McNeil is proud to cast his ballot for the first time in more than 20 years.

The 57-year-old had been homeless since his early twenties and voting was always on the back burner for him. He was too worried about where his next meal would come from or where he’d find shelter to actually deal with the logistics of casting a ballot. But this year is different.

He’s finally got a roof over his head.

“When I was homeless it was more about my well-being and a place to live. And I wanted to stay alive,” McNeil told BuzzFeed News. But now, he said, “I’m excited to be counted. I think it’s very important for me to vote.”

Having a stable home is crucial for someone's ability to vote. McNeil's case, though, is an exception: Resources to rehouse people experiencing homelessness are scarce, especially now during a pandemic that has decimated large parts of the economy and created such a great need for any kind of housing assistance.

Being homeless is not supposed to bar you from participating in the democratic process — unhoused people have the right to vote in all 50 states. But for people living on the streets, voting is in reality a challenge.That may only be more difficult this year: Advocates say the pandemic has thrown more obstacles into voters’ ways. From an increased reliance on mail-in ballots, to the threat of infection in crowded polling places, to ever-changing and confusing new voting regulations — these hurdles become much higher for voters who don’t have a permanent home.

The most recent national count by the federal government, in January of 2019, found that at least 568,000 people were living on the streets across the US. And the population of people who are disproportionately affected by these voting issues is only growing: While local and federal eviction moratoriums have helped keep a large number of people in their homes, there were still 30–40 million people at risk of eviction in August and few meaningful long-term protections in place to keep renters in their homes. Housing experts worry that more voters will face these barriers to voting in the presidential election and that it will disproportionately affect voters of color.

“This threat of homelessness and eviction has grown more rapidly in the coronavirus pandemic and recession than we have seen in previous recessions, and most of our solutions to this point have simply delayed the pain but not cured the wound,” said Joseph Lindstrom, director of field organizing at the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Additionally, voting rights experts warn that voting regulations already impact low-income communities of color — the same group that has been hit the hardest by this recession — more adversely than other communities. For the past two decades, voter enfranchisement has decreased significantly as states have introduced stricter regulations around voting.

Whether it’s strict voter laws that require documents like birth certificates or IDs for voter registration or it’s the need to physically get to a faraway polling place — the list of obstacles that housing-insecure folks face when trying to cast a ballot is long.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made that all worse. The coronavirus has brought large parts of the economy to a near standstill and created the most unequal recession in modern history. The majority of people who lost their jobs during the recession are people of color and low-income workers — and among them, many are increasingly finding themselves in vulnerable housing situations. Whether it’s people who are sitting in their homes, unable to pay rent and amassing an ever-growing amount of debt and waiting to be evicted, or folks who are experiencing temporary homelessness — more and more people are at risk of losing shelter. One early study estimates that 11 million households have fallen behind on their mortgage or rental payments.

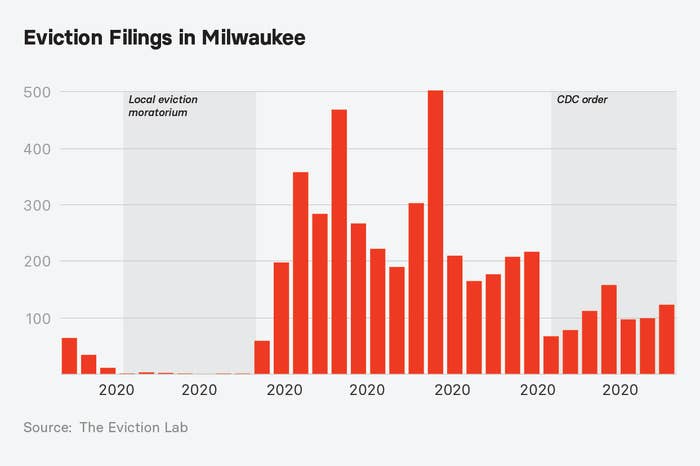

While there is no comprehensive data that documents the housing crisis for renters, the Eviction Lab of Princeton University has been tracking evictions for 17 major US cities for several years. According to their data, several cities in some key swing states, like Cleveland and Tampa, Florida, have seen landlords file hundreds of eviction filings since the pandemic hit, meaning landlords have started the paperwork of booting their tenants from their home. Another study from the National Low Income Housing Coalition estimates that the number of households at risk of eviction will be between 250,000 and 400,000 in Ohio and 830,000 and 1,080,000 in Florida.

There were roughly 4,538 people living on the streets in Wisconsin at the start of this year, according to HUD’s annual homeless assessment report from January — and that number likely went up as the pandemic set in.

In Milwaukee, the most populous city in the state, eviction filings initially slowed down in the spring of this year when the governor put a temporary ban on them until the end of May. But since the statewide moratorium ran out, landlords have continued to file for evictions, even after the CDC published regulations that forbade evictions nationwide.

“This is just a very forgotten population, when it comes to voter registration. And it's actually not a mystery, but it's somewhat ignored, because it really is very challenging,” said Laura Vuchetich, a volunteer who has been working with a group of people to register housing insecure people to vote in Milwaukee since early September.

“Everything that you hear about that various laws make it difficult to vote, multiply that by 5 for a homeless person,” Vuchetich added.

Vuchetich has been a political volunteer in Milwaukee for several election cycles. She’s worked on gerrymandering issues in the swing state and has registered voters at local sites like supermarkets. But this year Common Ground, the organization she volunteers with, decided to make a concerted effort to register voters who are newly out of work and at the brink of losing their homes, knowing that this population likely needed more support.

While a typical voter registration can take as little as 15 minutes, Vuchetich said that some applications can take several days, depending on what kind of paperwork people have.

“Even under the best of circumstances, our country is not fulfilling its promises to the people who are housing insecure,” said Myrna Pérez, director of the voting rights and elections program at the Brennan Center for Justice. “All anti-voter activities are going to hit members of communities on the margins the hardest. If you are a person who does not have a job that has flexible hours, then you’re not going.”

While every state makes the claim that you’re allowed to register to vote if you don’t have a residence, the practicality of how to make this work is difficult, said Pérez.

Some states ask for voters to affirm their address. Some states reject a person’s ballot if it’s not at the right precinct. There’s been a consolidation of where people can vote, giving people who lack transportation fewer polling places they can reach by foot or public transit. In Wisconsin, voters need to present a proof of address to register and present a photo ID to be able to vote in advance or on Election Day.

Then there’s the moving target of ever-changing regulations related to the coronavirus.

“With the processes changing on account of litigation, it’s hard for ordinary Americans to follow all of what’s happening and to know all the nuts and bolts. And when you’re in a vulnerable position, it’s going to be hard to get all the details on voting,” said Pérez.

Wisconsin is one of the key states, alongside Pennsylvania, where ongoing court cases impacted when voters would receive mail-in ballots, the New York Times reported. Most recently, the Supreme Court ruled that ballots that arrive after Election Day would not be counted.

To find folks who may be dealing with homelessness, Vuchetich and four other volunteers have spent the last few weeks going to places where people seek help — like soup kitchens, organizations where people give out free clothing, and shelters — standing in line with them and speaking to them about voting.

The places Vuchetich and her fellow volunteers have visited have been teeming with people, many of whom have lost much if not all of their income due to the pandemic. She said that the institutions she’s been working with have seen an influx of people in need.

But she also said the people she’s spoken with know how important this election is.

“Why are they working so hard to suppress it? It must mean something to somebody,” one person told her.

The practicalities of getting an ID during COVID

For McNeil, finding a home was a fortunate side effect of an unfortunate event. In April, he was exposed to the coronavirus in a shared space of a psychiatric ward, where he was receiving treatment for depression. When one of his fellow patients was diagnosed with COVID-19, he was moved into a hotel where he was quarantined and met his caseworker, Briana Perez-Brennan.

She was able to fight for a spot for McNeil at a hotel for people who are medically vulnerable (McNeil has had multiple strokes, was hit by a stray bullet years ago that still sits in his leg, and has no collagen in his knee caps, he said). Now she is in the process of finding him a government-assigned home.

But McNeil’s case is the exception, not the rule. Perez-Brennan, who is the bilingual outreach specialist at Pathways to Housing DC, has seen a spike in need for the kind of rehousing that McNeil is receiving and is foreseeing budget cuts in the future that will make it even harder to meet the needs of people like him.

McNeil has spent much of these last few months getting informed about politics by watching TV, first from his hospital bed and now in his hotel room. He watches the news religiously and has brought up current issues, from how to safely open up schools to the ever-climbing COVID diagnoses in the country, to Perez-Brennan on their weekly calls.

“I watch the news every day. On the streets I didn’t have anywhere to go and no TV to watch,” said McNeil. “So this is a blessing for me.”

Based on the news he has watched, McNeil said that he will cast his vote for Joe Biden. McNeil has been distraught over how President Donald Trump has handled the coronavirus crisis, he said.

“I want to be counted because I want a good president,” he said.

A path full of hurdles

Like many people who move around a lot, McNeil lost his government ID in the shuffle when he relocated from the hospital to the hotel where he is currently staying.

He was deeply saddened when he discovered his documents were gone. It had taken him two years to gather all the paperwork to get his ID in the first place and he knew just how important this little plastic card was for him to receive benefits or to prove his residency in the District of Columbia. (In DC, some voters may be expected to show proof of residence at the polls.)

Getting McNeil a new ID took three months and the help of at least half a dozen people.

Several employees of the city’s Department of Human Services had to gather hospital documents to prove both his name and date of birth. McNeil’s brother had to drive up from Maryland to bring him his birth certificate. With those documents, he was able to apply for a new Social Security card, which took several weeks to come.

Once that arrived, it was time for Perez-Brennan to book an appointment at the DMV for McNeil, which took several weeks due to reduced operating hours during the pandemic and a backed-up schedule.

Last but not least, McNeil had to figure out transportation to the DMV, which entailed another scheduling nightmare with the one dedicated bus that was shuttling medically vulnerable people from the hotel where McNeil was staying to doctor appointments and back.

He finally received his ID in August. He never would have been able to navigate these logistics on his own, let alone if he had been recovering from COVID-19, he said.

Thirty-three states required voters to present an ID to be able to vote or register to vote in 2019 (the first voter ID law was introduced in 2005 in Indiana), placing voters like McNeil at a clear disadvantage.

Donald H. Whitehead Jr., executive director of the National Coalition for the Homeless, works with organizations around the country that combat homelessness and can rattle off a long list of issues that keep housing-insecure folks from the polls.

In an election when mail-in ballots are vital for participating in the electoral process in a safe manner, people who don’t have a place to receive mail are at a particular disadvantage. Even voting in person can be difficult: Not only are people without stable housing more prone to have underlying health conditions, such as diabetes or asthma, it may also be harder for them to get to polling stations, said Whitehead.

“People recognize the importance of voting, they care about voting, but when you’re living on the margins, it’s not the number one priority,” he said. “If it was made easier for them to do it, then you get a higher representation of people [who are housing insecure].”

The mental toll of homelessness

Perhaps one of the most important things that has spurred McNeil to vote is his mental health. He’s in a good place now that he has a roof over his head.

Homelessness is “a big mental burden. I’ve been talking to a doctor about that. It’s a lot of depression,” said McNeil. “That was part of me not being healthy.”

Experts told BuzzFeed News that the psychological impact of housing insecurity on voter turnout is rarely addressed. Losing shelter is a traumatic event, especially for families and for people who are experiencing it for the first time.

Crystal Pitt, the director of homeless services at Northern Virginia Family Service, has seen the number of people who have recently lost their housing coming through her shelter swell since the pandemic hit in March.

“Our folks have been fearful,” said Pitt. They are worried about their safety and well-being, asking her, “Who’s going to be elected? And what will their priority be? Will it be us?”

Pitt, like other experts, believes that some people are really politically tuned in while others are overwhelmed and traumatized. While many people who are newly without stable housing voted in the past, it may not be something that they can focus on now.

“Rent eats first, and families struggling to pay rent make it difficult to manage other parts of a family’s lives, including how actively they can engage in their community,” said Alieza Durana from the Princeton Eviction Lab, which tracks evictions across the country.

Voting is also a social activity that is deeply anchored in a community, said Durana. Losing that community can have a discouraging effect on potential voters.

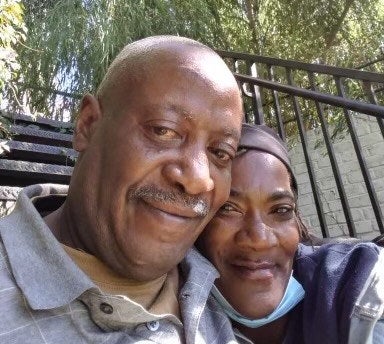

McNeil has found a small community to vote with. While decades of homelessness left him with few friends, he did find one person who is excited to cast his vote alongside him: his fiancé, Vanessa Gorham.

The two met on the streets of Washington, DC, 25 years ago, but decided to go steady at the end of last year. Like McNeil, Gorham has been homeless for decades — she’s been on the streets since she was 15. She’s also in a hotel waiting to be assigned an apartment to finally be housed. And like him, she’s pretty new to voting: She’s casting her first-ever ballot in this election. They planned to mail in their ballots together.

“It’s me and her voting together,” he said.