Earlier this month, a half dozen Maine police departments found themselves at the center of a very unusual hostage situation. To begin with, they had no idea where the kidnappers were hiding. Also, they had absolutely no negotiating leverage. And if they wanted to plumb their files to research the case, they were out of luck — their computers were locked, unusable.

They were being held for ransom.

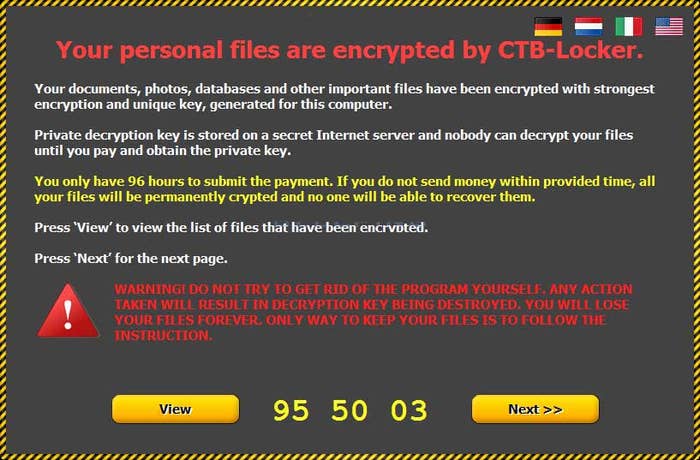

The Maine computers had been infected with crypto-ransomware, a family of malware that slithers onto a hard drive, encrypts it, and then demands a time-sensitive monetary payment, usually in bitcoin, to decrypt the data. Failure to pay by the deadline results in either permanent destruction of data — whether that's police records or that screenplay you've been working on for years — or a raised ransom. Infected computers look like this:

Ransomware is a decades-old technology that has enjoyed a resurgence among hackers because of its ease of use, its profitability, its recent confluence with cryptography, and its devious effectiveness. In the past couple of years, it has it become widespread. Those Maine cops weren't alone: Police departments from Massachusetts to Illinois have admitted in recent months to having been infected by crypto-ransomware; and hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of private citizens have dealt with the same. In the first six months after it emerged in September 2013, Cryptolocker ransomware infected more than 200,000 computers security researchers estimate. Over one six-month period last year, Dell researchers tracked another variant, CryptoWall, that infected some 625,000 machines and netted $1,101,900.

Crypto-ransomware is both effective, and surprisingly easy for hackers to control — it doesn't take complex skills or super-specialized knowledge to deploy. You can just buy it like you would Microsoft Office, or Candy Crush. Over the past year, the rise of so-called "affiliate lockers" — crypto-ransomware that is built and then sold in hacker forums — has enabled almost anyone with time, money, and basic technical competence to run their own extortion campaign. Then, all that's left is tricking someone into installing it on their computer. Once it's on there, you're fucked. You either have to pay up, or your drive stays decrypted. Hope you made a backup!

The attacks happen constantly; just this past Tuesday, the SANS Internet Storm Center reported a massive wave of emails bearing ransomware downloaders. A single company, the managed cloud computing firm Rackspace reported receiving dozens of the messages — one every 10 minutes; and that's a tiny fraction of the total. From there, all it takes is a faulty spam filter and one person to open an attachment for the ransomware to set up shop.

Crypto-ransomware is ubiquitous because it works. It asks average people to assign value to something that may be close to priceless, their data, and typically sets the price for the decryption low enough that there is no real choice. The Maine police departments paid $300 in bitcoin to regain control of their computers.

"Imagine yourself as a user," Santiago Pontiroli, a security researcher at Kaspersky Labs, told BuzzFeed News. "You have all your files encrypted — your family pictures — you check the price for the ransom and it's $300. So you put it on a scale, the price of your files and the price of your ransom. Most people will pay."

Most people may be a stretch; according to that Dell SecureWorks report on CrytpoWall, just 0.27% of those 625,000 infected computers paid up. And in an AMA on r/malware earlier this year, a Redditor named redditCTB claimed that 5–7% of the users he infected with CTB-Locker (the virus pictured above) paid the ransom. Still, that yield was enough to net redditCTB $15,000 a month, he claimed.

Indeed, ransomware can be astonishingly profitable. According to the 2015 McAfee Internet Threats Predictions, a single instance of the CrytpoLocker ransomware made over $250,000 in one month. The CryptoWall resulted in a total of over $1,000,000 in paid out ransoms.

"Cybercriminals have shifted their focus from showing how technically skilled they are to maximizing their profits," said Santiago Pontiroli, a security researcher at Kaspersky Labs. "This is organized crime."

It's a form of hacking that has proliferated so greatly because it requires scant technical expertise. According to Pontiroli, finding the kits to buy may be the most challenging part of the entire process; redditors denigrate redditCTB as a "kiddie" in his AMA, a reference to his lack of skill.

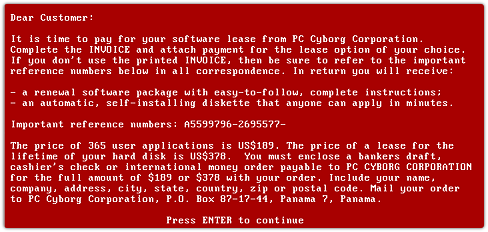

The earliest ransomware, which traces back at least to the late 1980s, took much more effort. Joseph Popp, a Harvard-trained biologist, mailed thousands of floppy disks that purportedly contained new information about the AIDS virus to the attendees of a World Health Organzation conference. Instead the program on the disk encrypted data on the computers and demanded a payment by mail to a PO box in Panama:

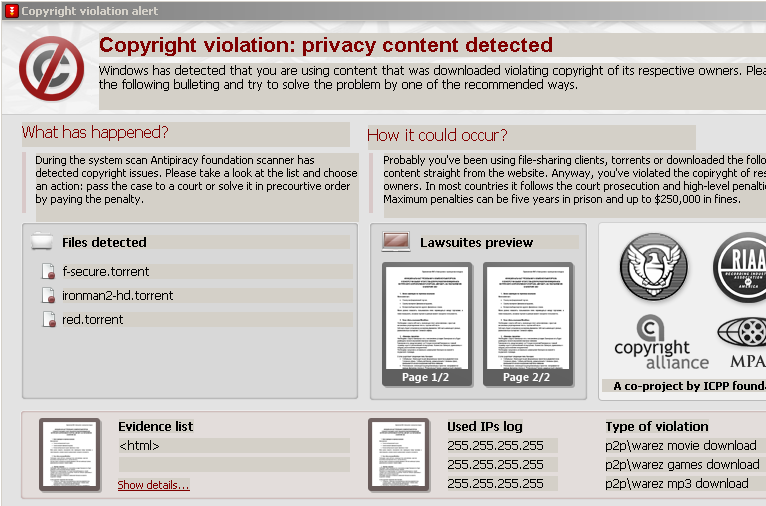

Popp — who was never convicted — claimed he was going to use the money for AIDS research. More recent ransomware, which began to appear in the early part of this decade, played on contemporary anxieties about pirated media:

Other contemporary ransomware included a Japanese virus that published web browsing data and demanded a ransom to remove it, and so-called "Police" trojans that claimed to be law enforcement and accused users of accessing child pornography, all of which can be taken care of, for a cost. According to Mikko Hypponen, chief research officer at F-Secure, most of this generation of ransomware came from Russia and the Ukraine: "There are competing gangs operating from Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Kiev, at least."

Many of these early 2010s viruses didn't encrypt data; they simply locked a user's homescreen on the payment information page. But the so-called "affiliate lockers," the bought and sold malware like CTB-Locker, has made cryptographic ransomware widely available (the going rate for a crypto-ransomware kit is $3,000). It has also made nontechnical prevention tactics much more important.

The easiest two ways to avoid having to pay a ransom on encrypted data are not opening strange email attachments — the vector by which the virus usually travels — and having a data backup. And some crypto-ransomware has been cracked; Working with the the National High Tech Crime Unit of the Netherlands' police, Pontiroli, along with colleagues at Kaspersky, were able to gain control of a CoinVault command and control server, and devise decryption keys.

Still, that's just one malware in a constantly evolving class. The only surefire way to discourage the spread of crypto-ransomware is for no one to pay a ransom — which is far from realistic. "This should be the policy always," Hyponnen said. "In practice, end users and companies very often pay up. The money they ask is often quite small, and they do deliver the results: the decryption tools almost always work." Indeed, Coinvault allows users to decrypt one file free of charge as a gesture of good faith — not unlike kidnappers releasing a single hostage.

And moving forward, there's the potential for crypto-ransomware to move beyond desktop and mobile to the vast network of connected devices we use every day. Imagine having to pay a ransom to heat your house on a freezing day. Or having to pay a ransom to start your engine to go to work. "Attacks like these are among the most credible attacks against IoT systems," Hyponnen said.

In the meantime, because of the potential embarrassment of a business or municipality disclosing that they don't have backups, it's hard to know just how many users have fallen victim to the trend. But as long as people keep paying, expect crypto-ransomware to continue spreading. "When you infect a computer you know you are going to get cash," Pontiroli said. "It's a numbers game."