The popular discussions on NeoGAF, the most influential fan forum in gaming, are largely what you would expect: speculation about the new consoles, arguments about the relative quality of new and old games, "what if" counterfactuals.

But then there was a thread started last February, which has in the past four months ballooned to 2,402 posts over 49 pages. It's not a discussion of screenshots from the forthcoming Grand Theft Auto V, or insider gossip about the connectivity of the new Xbox. It was an excerpt from the LinkedIn profile of a Microsoft Studios product manager. And the key sentence in the profile, the news nugget that has driven the thread to such wild proportions, is not the title of a new game or the suggestion of Xbox feature, but a piece of light legalese:

"I have been the primary producer on four unannounced new IP."

Gaming, like every industry, has its own vernacular, and this is perhaps its most peculiar case. For the uninitiated, almost every group in the game industry with a public face, from businessmen, to creatives, to journalists, to fans, uses "IP," or "Intellectual Property," to refer to game franchises or just individual games. A classic game IP is something like "Halo," which branches off into a fractal-like maze of sequels and comics and cartoons and fast-food tie-ins. But it can also refer to the creation of a single, new, original game with the goal of expansion. Game companies literally celebrate "new IP" — that's how Capcom described their new PS4 title Deep Down at the PlayStation 4 announcement event in February. The use of the term in gaming is as ubiquitous as it is, especially in the context of other popular art forms, bizarre.

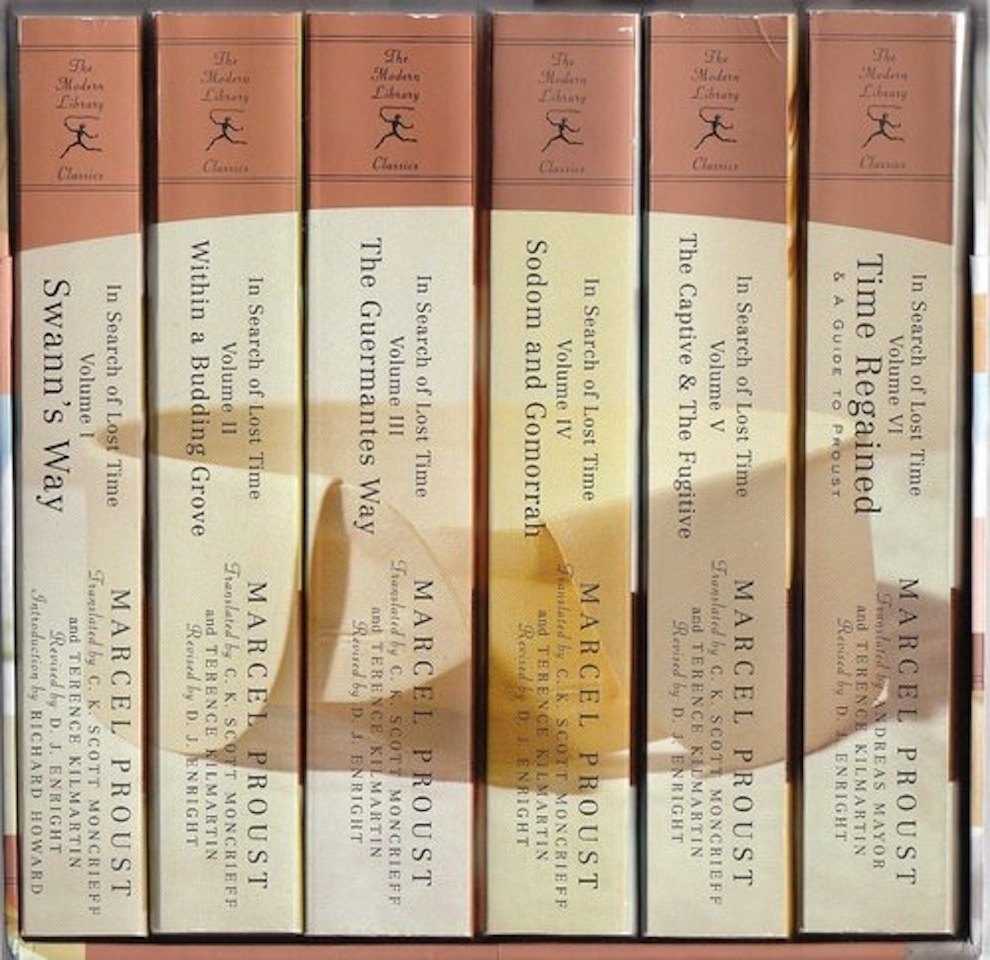

Imagine, for a moment, a book critic or book publicist publicly, celebratorily referring to "Four unannounced IP" (or for that matter, the "Harry Potter IP"). And then imagine book fans the world over losing their shit at the potential existence of four unique and new books (about which nothing is known) and their potential future monetization. To be sure, every creative industry has its own vernacular that would be potentially off-putting to fans — book editors are known to refer to their forthcoming titles as "horses" in a "stable" — but in no other industry has such a nakedly commercial term become a universally accepted way of speaking about creative products. About, well, art.

First, and most obviously, the NeoGAF thread is a testament to how starved core gamers are for new kinds of gaming. New "IPs," at the very least, mean new trappings for old play types, and at the most, experiments in both style and form. The fact that the very possibility of new and possibly forward-thinking games can send gamers into this kind of tizzy is a sad statement about the state of AAA gaming.

And the corollary to that statement is the fact that big gaming may simply be more openly corporate than big music or big book publishing or Hollywood (AAA games obviously share many characteristics with AAA Hollywood — the endless iteration on a handful of endlessly profitable franchises, with the occasional prestige project. And while Hollywood executives may publicly refer to "franchises," they almost never talk about "IP," unless it is in a legal context.) Before you dismiss this idea outright, consider the idea that we use the same language to describe a big game (AAA) as the language we use to describe a sure-thing bond issue — a near certain investment. Game designer and researcher Ian Bogost told me, "In the AAA sector, everything is completely driven by corporate concerns, and you can see how this style of thinking and speaking would trickle down into the rank-and-file. The tight control of publicity and PR is also a contributing factor — games are treated more like products than they are like creative efforts that happen also to be products." In other words, the profits-über-alles mind-set of big gaming companies sets the tone for the whole industry.

The downside to such a state of affairs is obvious: When corporate goals take total precedence over artistic ones, the quality of creative products often suffers (and we saw what I thought was a historically bad crop of sequels and retreads this past fall, during game's traditional AAA release season). But there's another way of looking at it: Gamers and game producers may simply have a more realistic view of creative production in 2013. The production and distribution of art has always been a negotiation between creativity and commerce (a fact visual art has been coming to tortured terms with for 50 years), and games may simply be the art form that most honestly admits this. Says Bogost, "You could see it as a virtue, a willingness among creators and players to see games as a weird intertwining of creativity and business concerns."

And gamers exert more influence over creative and business concerns in their chosen medium than perhaps any group of artistic consumers. Gamers protest narratives, sue companies that they feel have failed to deliver on their promises, are consulted by game companies to make sure their products meet expectations. (Not to mention the enormous backlash against the proliferation of downloadable add-on content.) Can you imagine a collector suing Damien Hirst because he didn't feel there were enough diamonds on For the Love of God?

The only part of the game world that is likely to find this interpretation galling is the auteurist segment of the indie games scene, and while Jon Blow or Team Meat would never in their lives refer to their games as "IP," IP is very much a part of their lives. As the story of Radical Fishing (which was re-imagined this year as Ridiculous Fishing in response to the 2011 ripoff Ninja Fishing) made manifest, game mechanics are uniquely vulnerable to what amounts to legally protected theft. As Bogost told me, "This talk about IP in games may also represent the anxiety our medium feels about its own relationship to IP." IP may be a way of claiming the uniqueness of games as units of culture worth protecting, not just endless clones in the app store.

That makes good sense. But I'm still left with the niggling sense that the ubiquitous use of the term, which inevitably connotes the business end of games (and is, frankly, a piece of jargon that makes no sense to anyone outside games), hurts the medium in the broader popular culture. If nothing else, it may be one of those powerful phrases that represents the way that gamers and game creators constrain their own thinking about what the medium can be. It's sort of like giving up before we even try. And for that reason alone, it's enough to wonder if we should be saying it as often as we do. What if we substituted "intellectual property" for something like, "universe" or "game," or "series," or just, oh, "original idea"?

Microsoft creating four original ideas in gaming? That would be something worth celebrating.