O’NEILL, Nebraska — On the day her life changed and the small town where she lives was divided, Angelica crouched inside a cramped compartment on the back of a truck used to transport pigs to the pork processing plant where she worked in rural Nebraska. It was a muggy August day and her job was thankless: hose down the cells and clean the feces left from the previous haul.

It was a long way from her native Guatemala, but Angelica, 30, and her husband, Walter, 31, liked the sleepiness of northern Nebraska, a place where all one sees for long stretches on the highway are pockets of yellow and purple wildflowers, acres of thick cornfields, and the occasional gigantic bale of hay. Everything had been hard in Guatemala — to be safe, to find work, merely to live — but here, in the tiny town of O’Neill, where they'd lived since 2016, they’d found some refuge. Their 7-year-old daughter went to elementary school here and they’d had another baby girl, four months earlier. Hundreds of other Latino workers had also settled here over the past decade.

Though they both had no legal immigration status, the couple had jobs on farms in northeast Nebraska, which is in a part of the country that is more reliant on the farming industry than anywhere else in the United States. They worked long days, in hopes they could find stability and put down roots. Only two years in, Nebraska had started to feel like home.

But on this day, she heard the voices of Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents.

“Stay where you are! Don’t move!” a male voice shouted from outside the garage as Angelica washed the trucks. The men in dark vests that read “POLICE Homeland Security Investigations” surrounded the garage, telling her and her fellow workers to come out with their hands up.

The agents loaded them onto a stuffy bus, headed almost two hours away to the nearest ICE processing center. Angelica stared blankly out the windows, trying to reassure herself that Walter would be there for their kids when the babysitter dropped them off that afternoon. He might not know where she was, she thought, but at least the kids would have their father.

When they got to the processing center, agents led her inside a large white tent that they’d set up in anticipation of the raid. Angelica saw practically all the Latinos from O’Neill — eating warm soup and crackers as ICE agents fingerprinted them and got information.

Her eyes scanned the tent for people she knew. Then, she saw him: Walter, sitting by himself in clothes that were dirty from working at a local cattle ranch, his hands cuffed and chains around his waist. Her heart dropped.

Their 4-month-old girl and 7-year-old daughter would not have their parents that day — and their future in O’Neill, and America, was now uncertain.

The ICE operation on Aug. 8 resulted in the arrests of 118 suspected undocumented workers — mostly in Nebraska — at multiple worksites, including a hydroponic tomato greenhouse, a pork producing plant, a potato factory, and a cattle company. Some laborers were placed in ICE detention, while many were released and told to go to immigration court for their deportation proceedings.

It was one of the largest worksite raids in years and part of a major push by the Trump administration to increase enforcement efforts at workplaces across the country.

For more than two days after the raid, two dozen migrants across the town slept on the carpets and in between the pews of O'Neill's Spanish-language Pentecostal Church, fearful that ICE would go door to door looking for people to arrest. Some who came were congregants, many were not. The pastor of the church said the panic and trauma was worse than when a family member dies.

“We were the happiest before this, but now? We’re a sad community.”

And in the weeks since, the raid has reverberated throughout the once thriving immigrant population in O’Neill, a town of just over 3,600 people, so isolated that it’s the largest town in a 60-mile radius. Fear has gripped the community of Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Mexicans. Many now rarely leave their homes, worried that ICE may be around the corner or that long-time residents will call the authorities on them.

According to locals, more than a dozen immigrants have left O’Neill. Families have split up. And many workers caught up in the raid can no longer find jobs, subsisting on donations that at some point will end.

“In this town, I don’t think there’s anything — it’s finished,” said Rosa, a 65-year-old woman from Mexico who was arrested working at the massive hydroponic tomato plant on the edge of town, where many of the laborers were picked up. “A lot of people have moved away. We were the happiest before this, but now? We’re a sad community.”

The raid also shook long-time residents of O’Neill, a deeply religious, conservative town that voted overwhelmingly for President Trump, exposing fault lines that divided friends who rarely, if ever, spoke about immigration. While a spirited group of teachers and advocates rallied in support of the workers arrested in the raid, others were less sympathetic. Many of these arguments took place on Facebook, others happened in public.

The immigration status of workers, their effect on the economy, and their place in the community were always assumed but never spoken about. The raid changed that.

“We’re a divisive community right now. The immigration system has got us split right down the middle,” said Pastor Brian Loy, 56, who runs the First United Methodist Church in town and helps run a food bank for the affected families every week.

Loy has lost friends over his support of the laborers, has been “shunned” downtown, and has had congregants confront him, he said. Most people, he believes, are ignorant of the immigration system, like he was, assuming that undocumented workers had unlimited access to government welfare. “I didn’t understand that until I got in the middle of this.”

The food bank he helped set up for those affected by the raid gets its donations mostly from outside cities, not O’Neill. As the weeks went by, more laborers came out of hiding to visit the pantry — Loy doesn’t know how they ate before then. Some waited outside the church for hours before Loy and his crew begin serving lunch and handing out supplies — so they started providing breakfast.

The crisis gave his church a sense of purpose, a mission to help those in need.

While residents never expected such a raid, the town was in fact on the front lines of a major shift in immigration policy under the Trump administration, which has emphasized investigations and operations at worksites that employ undocumented workers. Arrests of undocumented immigrants at workplaces have skyrocketed — up more than five times from the previous fiscal year as of July, from 172 to 984, excluding the raid in O’Neill and a later major operation in Texas — as the administration cracks down on what they believe are businesses taking an unfair, illegal advantage.

In this case, agents arrested Juan Pablo Sanchez Delgado on multiple federal criminal charges, alleging that he was a ringleader of a scheme that provided undocumented workers with fake documents, funneled them to the businesses ICE eventually raided, and eventually skimmed money from their paychecks. Sanchez Delgado has admitted in court that he came to the country on top of an inflatable swimming pool over the Rio Grande and did not have legal status.

During the course of their search warrants at the worksites allegedly involved, the agents came across the laborers and arrested them on immigration violations, a change from the Obama administration which during its latter years avoided mass arrests of workers.

O’Neill is a community with deep roots tied to its own immigrant history. An Irish-born general who fought in the civil war, John O’Neill, founded the town in 1875, bringing with him three groups of fellow Irish immigrants. Nowadays, O’Neill, like the rest of the Great Plains, is predominantly white and economically dependent upon agriculture. The last census estimate in 2016 found that just over 250 Latinos lived in O'Neill.

“Without immigrants, who would process potatoes, pick tomatoes and chiles? We do all of the work.”

The industries of specialty crops, livestock operations, and processing in the area “are dependent on hired labor in a very tight labor market,” said Brad Lubben, a professor of agricultural economics at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. The unemployment rate in the county is just over 2%, half the country's overall rate. “Historically, immigrant labor has been a very important part of that labor force.”

But immigrant workers caught up in the sweep don’t think they’re acknowledged for the labor they provide. While many residents in town work in the local hospital, the migrant laborers toiled in, at times, difficult conditions at the local farms and processing plants.

One worker who picked tomatoes at the hydroponic plant said on summer days it was so hot that he felt as if he were burning in hell.

“The government doesn’t appreciate the work we do,” said Rosa, the 65-year-old who worked at the tomato greenhouse and was arrested. “Without immigrants, who would process potatoes, pick tomatoes and chiles? We do all of the work. They don’t appreciate it.”

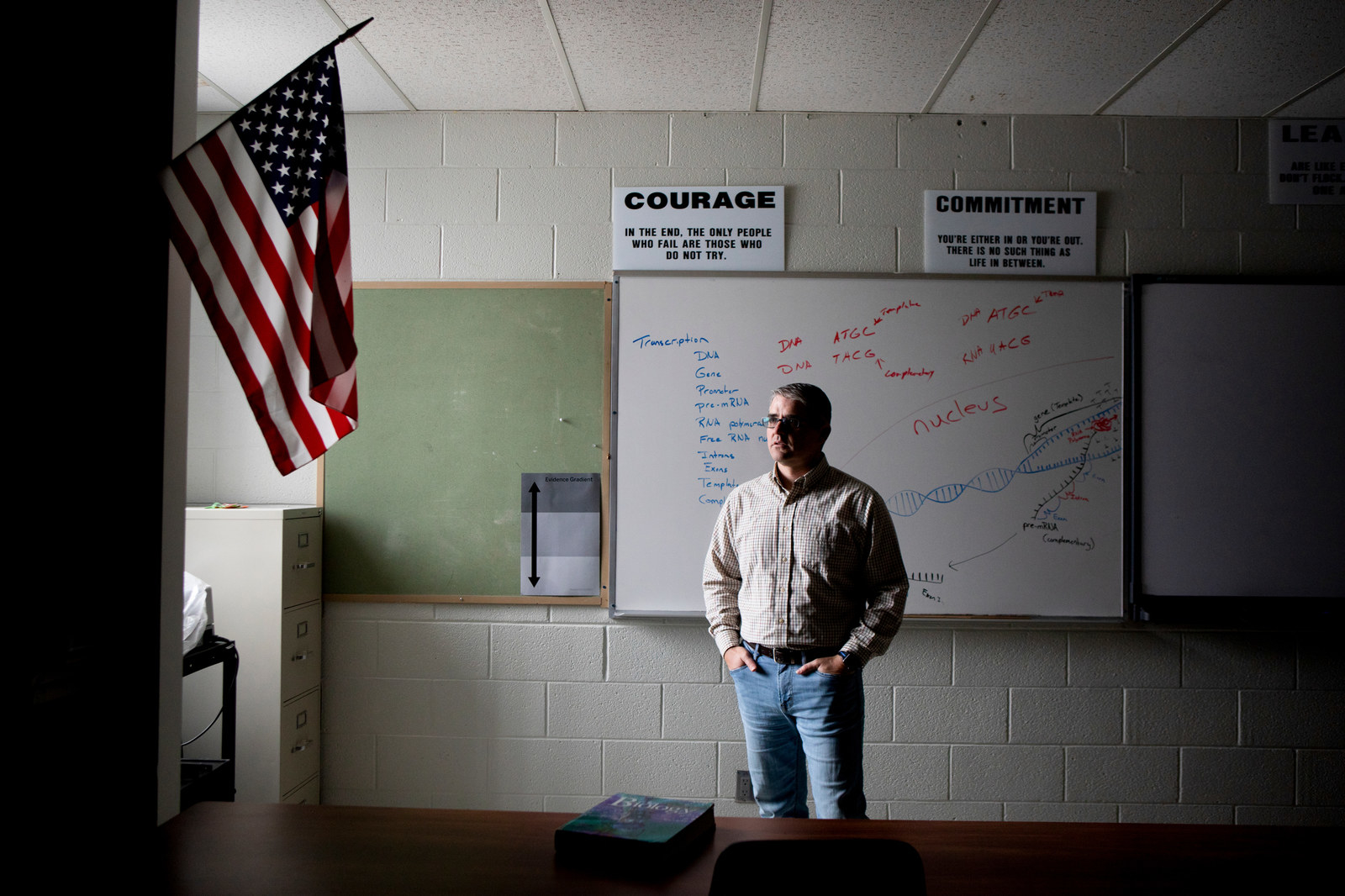

There were many in O’Neill who wanted it known that they did support the migrants and brought up the town’s own immigrant history. Bryan Corkle, a high school science teacher and wrestling coach, helped organize a rally outside the local courthouse in support of the arrested workers, telling local media that these people’s lives had been upended.

More than anything, he thought of one of his students, Stephanie Gonzalez, a 17-year-old senior honors student on the cheerleading team whose mother was arrested at the tomato plant. Since the raid, ICE has kept Gonzalez’s mother, who had previously been deported, in detention. Gonzalez and her two brothers, ages 1 and 7, moved to another town more than an hour away to live with relatives. She was gone for a month but has since returned to O’Neill to live with her best friend’s family.

“It’s a very hard thing to talk about, even for me, because it still doesn’t feel right for a mother to be away from her kids when she has raised all three of us by herself,” she said. “Family separation is not the solution to ending illegal immigration.”

One man who supported the raid said he believed it would send a much-needed message to the industry — hire authorized workers or get caught.

Like many in town, Corkle has had long, “passionate” conversations about the raid with a friend. In this case, it’s Dwaine Marcellus, who owns his own farm a few miles outside of O’Neill. Following the sweep, and their spirited debates, Corkle and Marcellus realized they’d never agree with one another.

Marcellus, who grows soybeans, dry beans, and corn on his farm, believes that greed, not necessity, is the reason behind farms hiring undocumented workers. His four employees are Americans, and he pays them a fair wage. He supported the raid and believed it would send a much-needed message to the industry — hire authorized workers or get caught.

“This,” he predicted, “could be the best thing that ever happened.”

As for the workers, they knew the risks when they came to the country, he said. The demonstrators outside of the courthouse made fools of themselves and were being too selective — why don’t they help long-time residents of O’Neill or protest for them?

Down at the local bar and grill, Chesterfield West, which is tucked at the end of O’Neill’s two-block downtown, near the faded green shamrock painted in the intersection and across from a western wear store, many agreed with Marcellus. Over beer, steaks, and burgers that “have never been frozen,” local residents, most of whom voted for President Trump, said ICE was simply doing its job. After all, they said, the US would not be a country without its immigration laws.

There were others, however, who said the raid opened their eyes to the personal impact of the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrants. One woman, who refused to provide her name for fear of the reaction in town, said she’d voted for Trump but that the operation had altered how she thought of immigration enforcement. The agents should have arrested the alleged criminals and helped the workers who were just trying to get by, instead of picking them up.

“When it hits close to home, it makes you think more about what’s happened,” she said.

For those caught in the raid, survival is dependent on food banks and landlords forgiving rent for a month or two. One group, O’Neill Cares Coalition, helped some laborers pay for a month of expenses, and the ACLU of Nebraska and the Immigrant Legal Center have provided immigration attorneys.

Many workers now gather at a small hall at Loy’s church every Thursday, sitting beside one another at small white tables and waiting for volunteers to hand out boxes of goods like cheese, bread, and meat. Nachos were served for lunch one afternoon in September.

Laborers still replay what happened that day and where they were when the ICE agents came to their place of work. Some say they’ll attempt to get visas designated for victims of crime while others without lawyers don’t know what to do. It’s mostly quiet except for the children running circles around the tables playing tag.

One woman who’d voted for Trump said the operation made her rethink immigration enforcement. The agents should have arrested the criminals and helped the workers, instead of picking them up.

Rosa, the worker at the tomato greenhouse who worked 12-hour shifts, six days a week, says she, like many, came to the town on the advice of a friend more than a decade ago. She cried when she started to think about how she’ll pay for food, electricity, or rent in the upcoming months as her deportation proceedings ramp up.

She pointed to a young couple at another table holding a baby girl. It was Angelica and Walter.

“Can you imagine how they feel?” she asked. “I can have a tortilla with beans but they have a baby and another little girl to feed and take care of.”

On the day of the raid, Angelica and Walter pleaded with the ICE agents to let them call their babysitter. They were never allowed to, they said. Instead, the babysitter, scared of ICE coming for her too, dropped off the children at the local elementary school, where teachers cared for them. That night, the girls went to stay with the school’s assistant principal, Jill Brodersen. The 7-year-old asked for her mother’s whereabouts, and all Brodersen could tell her was that she was safe and that people were looking after her.

“My heart went out to their mom, not knowing where her kids were. I just hoped she had a sense that they were loved and taken care of,” Brodersen said in August.

In the middle of the night, Angelica and Walter were finally released. To this day, their 7-year-old daughter asks them why the two never leave the house. Are they on vacation? she wonders. But she’s starting to pick up on what happened that day, imploring her mother to never go to work “if you don’t have papers.” She doesn’t want to be separated again.

As for their future, Angelica has a pending asylum case she hopes to fight in court, and they’ve drawn up a plan for what happens to their girls should they get swept up and arrested again.

They have not found jobs.

“We don’t know,” she said, crying, “what will happen now.” ●