Morgan Wallen is apparently sorry again. His sophomore album, Dangerous: The Double Album, has been the No. 1 album in America for three weeks in a row. He broke the country streaming records by a lot — the album was streamed 240 million times in just the first week, more than double the previous record held by Luke Combs. This was to be the album that cemented Wallen’s status as the genre’s top draw. But instead, he’s making news because he is sorry...again. This time, the apology comes after TMZ posted a video last Tuesday, filmed by a neighbor’s Ring camera, featuring Wallen drunkenly (and vigorously) using the n-word to refer to a person in his group.

It is startling to watch how easily the word came to Wallen. TMZ bleeped it, and yet I have no trouble imagining he said it with relish, pouncing on the hard R. I have no trouble imagining he said it like he’s familiar with it, like his mouth has been there before. This is an artist who has traded on his authenticity since he first came on the scene as a 2014 contestant on The Voice. Who sang in his 2018 single that “I live the way I talk.” Wallen has positioned himself as a mullet-and-blue-jeans, what-you-see-is-what-you-get kind of guy. And it’s impossible to watch the video without this in mind.

It’s Wallen’s second apology in four months. In October, Wallen apologized after his Saturday Night Live appearance was canceled. He was pulled off the show for violating SNL’s COVID-19 rules after a video surfaced of him partying. After the incident, Wallen released a video on Instagram saying, “I have some growing up to do.”

Wallen’s apology for the n-word video contains similar themes. “I’m embarrassed and sorry,” the statement reads. “I used an unacceptable and inappropriate racial slur that I wish I could take back. There are no excuses to use this type of language, ever. I want to sincerely apologize for using the word. I promise to do better.”

The country establishment moved quickly to distance itself from Wallen. His record label says his contract is “indefinitely suspended.” Country radio is dropping Wallen — a particularly big deal in a genre where radio is king. His booking agent parted ways with him and he’s been booted off curated lists on the major streaming services. The Academy of Country Music said he won’t be eligible for its 2021 awards. For all intents and purposes, at the time of publication, Wallen has been put on a very firm timeout.

That there is swift and serious action on the part of country music’s establishment to get itself away from Wallen’s racist behavior seems promising. But to take it as an indication that country music is ready for some kind of racial reckoning is to seriously underestimate how much the genre is in love with white men in search of redemption. Country music needs redeemed white men more than it wants its Black artists to be successful. This is not new — it’s baked into the DNA of country. This cycle of forgiveness serves as a stand-in for absolving the genre’s establishment, over and over again.

Charley Pride, the north star of Black artists in country music, recalled in his memoir the story of how singer George Jones once drunkenly painted “KKK” on his car, apparently as some sort of joke. It’s the kind of cruelty and degradation Pride often endured over the course of his career. It wasn’t always that straight forward and obvious — Pride also tells the story of when singer Webb Pierce said to Pride, “It’s good to have you in our music.” Pride wrote that the statement made him “bristle.” He told Pierce, “It’s my music, too.”

Pierce may have said that in the 1960s, but the notion that Black artists are mere visitors in country music hasn’t gone anywhere. This is not just about the genre’s popular mythology as “the white man’s blues.” It’s about the dearth of resources it dedicates to Black artists. Take, for example, Mickey Guyton, whose label was hesitant to position her as a country artist for so long that this year she became the first solo Black woman to be nominated for a country Grammy without ever putting out a country album. And who could forget when the Recording Academy's country committee rejected Beyoncé's “Daddy Lessons” from country Grammy award eligibility? Radio stations, meanwhile, insist on dedicating extraordinary airtime to white men in the genre, at the expense of women and Black artists.

When it comes to the death of a legend, even that could not be entirely divorced from a pattern of carelessness.

Black people are foundational to the creation and advancement of country music. But the genre bends over backward trying to keep race out of the conversation. And when the labels and radio stations and major institutions do wade in, it’s in a whitewashed, mild way. Last year, amid a colossal Black Lives Matter conversation, when country artists were finally willing to engage with an urgent moment about race, the Country Music Association advertised that its award show would have “no drama.” This is, of course, code for no discomfort.

And how do you produce an award show in the middle of a revolution but with “no drama?” You make safe choices. The show opened with Darius Rucker, perhaps the genre’s current biggest Black star at the moment, performing “In the Ghetto,” which is certainly, uh, a choice. It also used the night to give Pride the Willie Nelson Lifetime Achievement Award. Pride died of COVID-19 a few weeks after the “largely mask-free” award show, at 86.

There are questions as to whether he contracted the illness at the indoor event. There were no audience members in attendance, but the nominees and performers were present. After Pride’s death, the anger was palpable. Singer Maren Morris tweeted, then deleted, “I don't want to jump to conclusions because no family statement has been made, but if this was a result of the CMAs being indoors, we should all be outraged.” Guyton tweeted, “We need answers as to how Charley Pride got COVID.”

That questions about Pride’s death exist at all is a nod at something bigger: a recognition of a pattern of carelessness on the part of country music when it comes to treating its Black artists. They don’t get played on the radio. They don’t get the label support they deserve. And when it comes to the death of a legend, even that could not be entirely divorced from a pattern of carelessness.

There is a beautiful abundance of brilliant Black talent in the genre right now. Reyna Roberts has strong Carrie Underwood energy. Willie Jones is the kind of cheeky singer Country radio should love. Chapel Hart will brighten up your day. How is Brittney Spencer not being played by every station? And I doubt Breland cares if you think he’s “country enough,” but he undoubtedly is.

The charge is being led by Guyton, who has become both the face of the ascendant Black country renaissance and the singular distillation of country’s failures to promote and back its Black artists. Right now, there is an organic social media campaign to push her EP, Bridges, to the top of the iTunes charts. She currently sits at No. 8, while the top six spots are occupied by…Morgan Wallen.

Black people have always existed in, pushed, and celebrated country music. But the industry has not made much of an effort to love them back. By contrast, country loves giving white men a second chance. Its institutions do so on a regular basis. Few have even heard the story of George Jones painting “KKK” on Charley Pride’s car, and it will likely do little to dent his status on the Rushmore of country music. In 2015, Jason Aldean wore Blackface for Halloween and then four years later was crowned Artist of the Decade by the Academy of Country Music. Songwriter Dallas Davidson, who has written multiple No. 1 songs, drunkenly uttered the n-word and anti-LGBTQ slurs in 2014, and after a few quiet years, now he’s back: He has a song on Luke Bryan’s latest album, as well as — you guessed it — Morgan Wallen’s.

How country handles the fallout of Wallen’s disgrace will say a lot about country’s readiness to deal with its racism problem.

Wallen may be in a bad publicity moment, but he’s not exactly bad for business. Despite the scandal of the video, his streams did not suffer. In fact, digital sales for his album went up — by 1,220%. He is expected to close out a fourth week at the top of the US albums charts. It appears to be a counterreaction to the forceful response to his drunken video.

That he is still selling so well will surely test the resolve of a country establishment that says it wants to turn a corner on race. How long can they punish an artist who has so publicly told on himself, but who is also a reliable money-printing machine? Can they, as the saying goes, “stand in the way of a hit?”

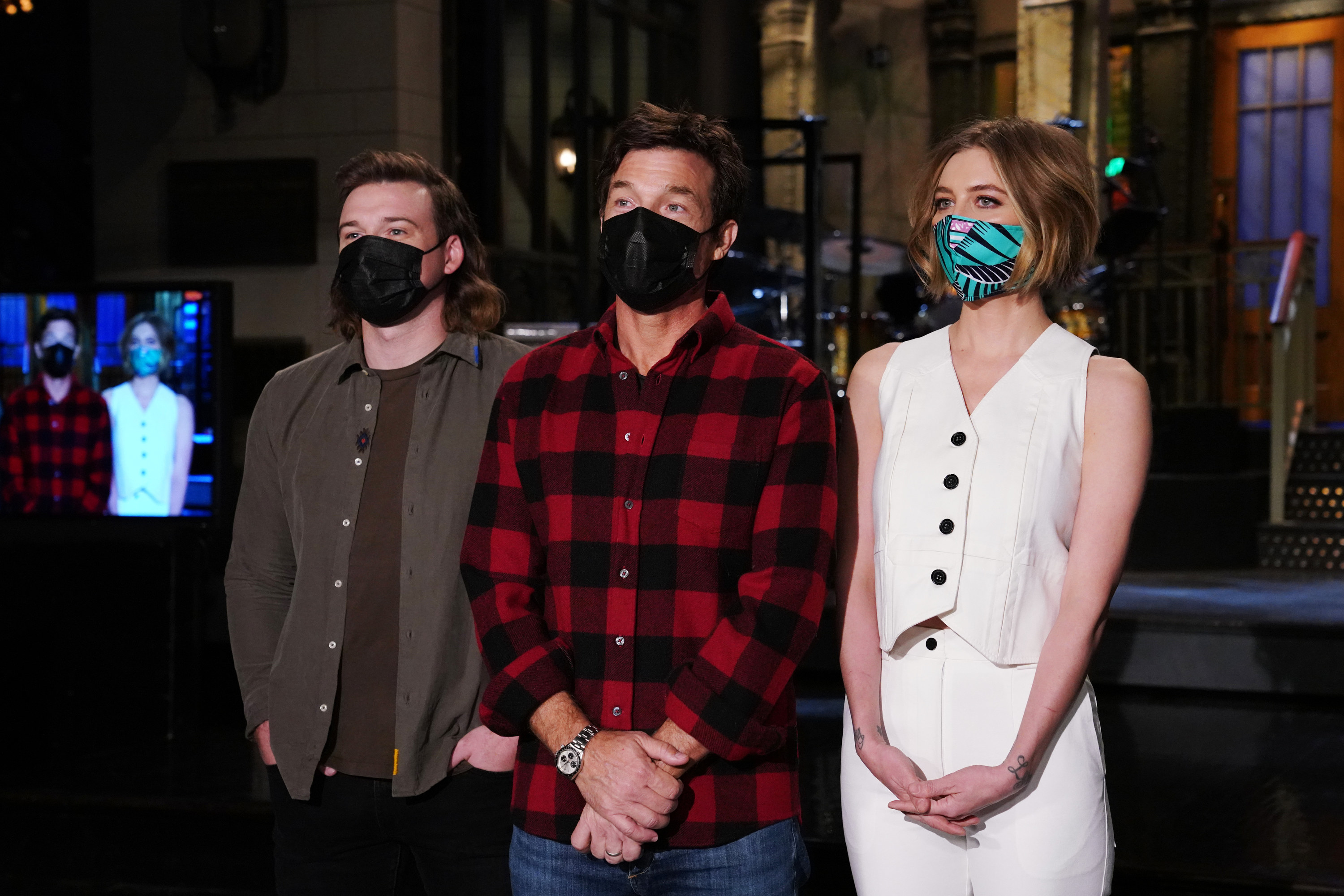

A lot of energy has gone into creating and maintaining the Wallen arc. After his 2018 album If I Know Me proved he can be a force on the charts, Wallen’s star was ascendant. He won New Artist of the Year in 2020. And just two months after he was pulled off SNL, the big marketing machine kicked into gear and he returned to the coveted musical guest spot in December. The show even made a skit out of the incident that got him in trouble, when Wallen and host Jason Bateman raised a bottle “to no consequences!” The Washington Post noted that, yes, the incident gave him publicity, but he is still poised to be the future of country music.

This is now true in more ways than one. How country handles the fallout of Wallen’s disgrace will say a lot about country’s readiness to deal with its racism problem. It will signal its desire to either explicitly acknowledge it, or vow to go further down the “no drama” road. Country needs a deep excavation of its own history of sidelining Black artists and redeeming white men. Its institutions need to confront why, at a time of blossoming Black talent, those artists still find themselves not being supported.

I want to believe that Wallen’s story is the inflection point some believe it is. But based on repeated patterns, we can assume the inevitability of Wallen’s redemption looms in the distance. Perhaps a crew of marketing executives are already huddled in Zoom calls right now, planning it.

When the moment arrives, the debate will likely center on whether he deserves a second chance or not. It’s exactly the wrong question. The right questions are: On what basis should we judge him? What signs of change should we look for? What work will Wallen do to show he is sorry? And what can the system that enabled him do to promote the artists it has left behind?

A country executive recently told the LA Times that they are “fully expecting” a Wallen comeback, perhaps him “performing a tearful acoustic comeback single on the 2022 CMA Awards. There won’t be a dry eye in the house, and everyone will pat themselves on the back for steering his redemption.”

That sounds about right. And if this comes to pass without the country industry seriously engaging in its overdue reckoning, the tears won’t be just for Wallen’s redemption. They’ll be for country music doing what it always does: making a mistake, then forgiving itself. ●