As ephemeral, encrypted messaging apps have grown in popularity, it’s become increasingly common to see them used in the workplace, whether to discuss sensitive information or to complain about colleagues. But a new ruling in the ongoing trade secrets lawsuit between Google’s Waymo and Uber, which is set to go to trial next week, could impact how free employees feel to use these apps at work.

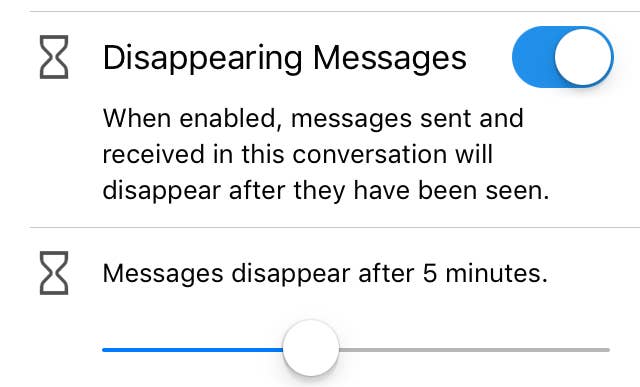

Ordinarily, most companies are under no legal obligation to keep records of digital communications. (The federal government and the heavily regulated financial services sector are exceptions.) But if a company is being sued, or has reason to think it will be soon, it’s required to keep records of written communications. This is when the use of technology that doesn’t automatically retain message histories becomes a problem.

During the discovery process ahead of the Waymo v. Uber trial, Waymo discovered that Uber instructed its employees to use Wickr, an ephemeral chat client intended for use in the workplace, to discuss its self-driving technology efforts. Uber employees were using Wickr after the date that the judge presiding over the case, William Alsup, later ruled the company could have reasonably expected Google would file suit. Waymo has argued that this proves Uber preemptively covered its tracks, and in so doing, inappropriately interfered with legal proceedings by deleting evidence, also called spoliation.

“The judge could have come out and said that the use of ephemeral messaging … constitutes spoliation and he didn't do that,” said Wynter Deagle, a trial attorney who coauthored a paper on ephemeral messaging and legal discovery.

The Waymo v. Uber suit has led some tech companies to question whether using ephemeral messaging at work is a good idea.

Alsup could have sanctioned Uber for using ephemeral messaging. But instead, he ruled on Wednesday that while Waymo can mention in court that Uber used Wickr “as a possible explanation for why Waymo has failed to turn up more evidence of misappropriation in this case,” it can’t use that evidence to “invite improper speculation [or] vilify Uber without proving much else.”

University of Toledo law professor Agnieszka McPeak is working on a book about the legal implications of ephemeral messaging. She said that, while the judge took a moderate approach in his decision, employers should nonetheless take the order as a warning when it comes to using ephemeral messaging apps at work.

“It should signal that there's a risk. It's going to be looked at poorly in litigation by a judge. It will be looked at with suspicion,” she said. “It's positive in the sense that it's not a ruling that tells the jury to presume something nefarious, but at this point, it's something that companies and individuals need to pay attention to.”

Alsup also wrote that Uber should be allowed to defend itself by referencing Waymo’s use of similar technologies. An Uber spokesperson reached for comment pointed to an earlier filing by Uber’s lawyers, which says, “in addition to developing and using multiple ephemeral messaging systems, for a decade, Google has been deleting all of its employees’ chat messages on Google Hangouts, unless the user takes affirmative steps to save them. Waymo has followed this policy since its inception.”

A spokesperson for Waymo’s legal team told BuzzFeed News that the company’s issue is not with ephemeral messaging in general, but with Uber’s particular use of Wickr to conceal bad acts.

The judge’s ruling in Waymo v. Uber is preliminary. Alsup could issue additional orders after the case goes to trial, but the final decision as to whether Uber used ephemeral messaging in bad faith or as a standard business practice rests with the jury.

“I wouldn't be surprised if, when they pick the jury, they don't ask ‘Do you use Snapchat? Or Whisper? Or Slack? Or Signal?’” McPeak said. “That might be part of what they want to ask the jurors just to understand if they're fluent with that part of new technology.” Jury selection for the trial began earlier this week.

The arguments over ephemeral messaging in the Waymo v. Uber suit have led some tech companies to question whether using these technologies at work is a good idea. Joel Wallenstrom, Wickr CEO, said as the case against Uber has unfolded, lots of companies have reached out to him, asking how they can continue to use ephemeral and encrypted technologies without creating the impression that they’re trying to cover something up.

“These are startups — close-to-IPO-type startups — saying, ‘We have no policies for this,’” Wallenstrom said. “I know a lot of people who are saying, ‘Hey, we’re reading about this and it strikes me that our employees are probably using these tools, so can you help us understand how to put policy in place?’”

Even if a company isn’t using encrypted chat to discuss sensitive matters at work, lawyers say it’s a good idea to have an information retention policy in writing. This is something most Fortune 500 companies with giant legal teams already have, allowing them to delete unneeded files on a regular basis without creating the impression they have something to hide. But smaller companies often miss this essential step, putting themselves at risk.

“With startups, sometimes the company moves faster than the legal does,” said Deagle. “So they do things sometimes without documenting the way that you see in a larger, more well-established company. From an employee perspective, you’re always safest when your directives are in writing because there’s no question of who told you to do what and when.”

Typically, if you’re not sure whether or not to put something in writing, the easiest thing to do is make a phone call. A phone conversation, by default, is not recorded, and so failing to record it doesn’t count as erasing it. McPeak argues that ephemeral messaging works the same way, and that it has the potential to replace phone calls, giving a younger generation of workers who are more comfortable talking with thumbs the same privacy expectations — without having to talk out loud.

"It's OK for a lawyer to tell a client to pick up a phone and have an unrecorded phone call,” said McPeak. “That's what I think using Signal and Slack and Telegram and all these apps is, essentially: the new voice conversation."