What do you call a typewriter with no keys? Though it sounds like a riddle, Stanford historian Tom Mullaney told BuzzFeed News, it’s not. A Chinese typewriter has 2,500 characters but zero keys, and Mullaney owns more of them than anyone else in the world.

The Chinese language has over 75,000 characters — way too many to fit on a keyboard with a single key per character. The inventor of the original Chinese typewriter slimmed that number down to just the 2,500 most used characters, but even still, that’s too many to type out as you would on an English-alphabet typewriter.

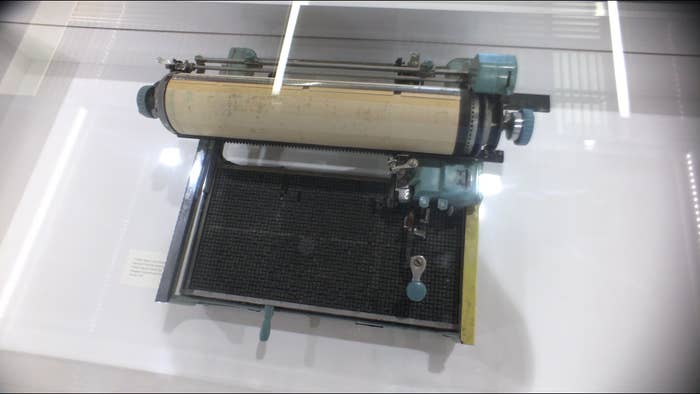

On a Chinese typewriter, those 2,500 characters correspond to 2,500 tiny metal squares, which lie side by side in a tray bed. Instead of pressing individual keys with individual fingers, the typist uses a knob in each hand to move a scroll of paper up and down, left and right over the keys. When the machine is on top of the character you want, you press down on a lever. Then, Mullaney explained, the metal piece gets pushed (or sucked up) into the type chamber, inked, and struck the surface of the paper, before being ejected and spit back out into the spot in the grid where it was.

Here's what that process looks like:

View this video on YouTube

That’s a lot of steps for just one character. Each stroke of the lever takes just a second, but the thing that slows Chinese typists down, and for years made them much slower than Western typists, is the distance between characters — especially because the typewriter's characters were organized according to what Mullaney called “dictionary order.”

“The problem is, just like a dictionary, words don’t necessarily go together,” he said. “'Aardvark' and 'apple' don’t show up in sentences together, despite being in the same part of the dictionary.”

So in the '50s, typists started dumping out all of the characters and building their own custom tray beds from scratch, using tweezers to array characters based on how commonly they were used together.

The thinking was, “If I have to write the name Mao Zedong, which is three characters, over and over, why would I move across the tray bed?” Mullaney said. “Let’s put them right next to each other.” The result was “completely personalized, completely individualized, completely idiosyncratic” tray beds.

This innovation made typing much faster, according to Mullaney. “If the top speeds in the 1930s and '40s was 20 characters per minute, and that was for a very fast typist, after the 1950s ... you had top speeds of 55, 60 characters per minute,” he said. “That’s a three-time increase in the speed of the machine just by rearranging the characters in the tray bed.”

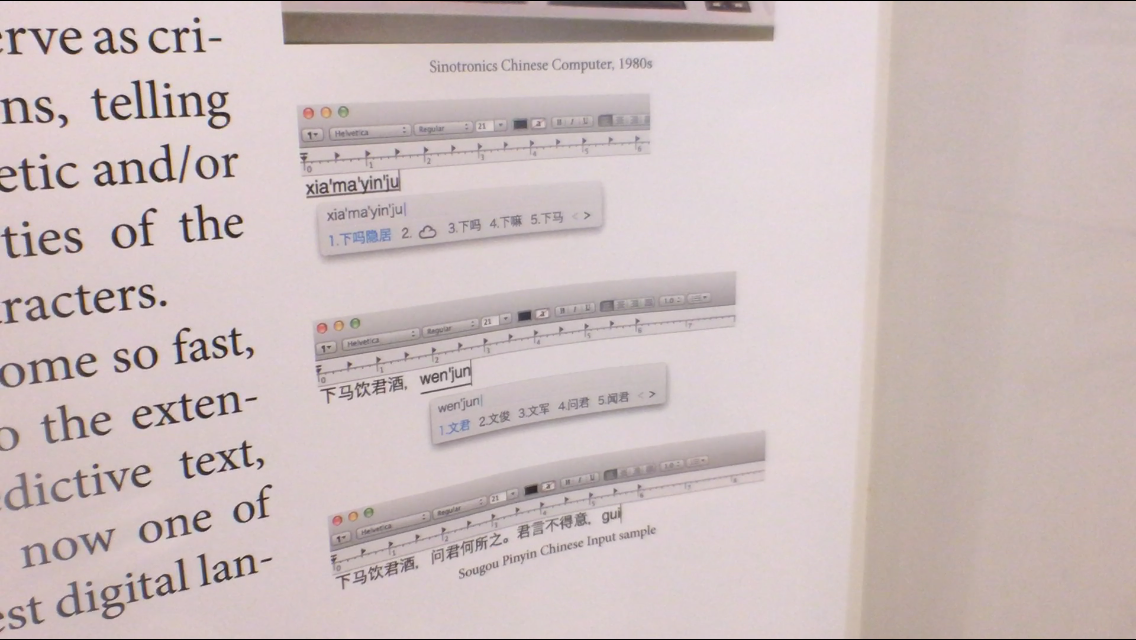

But he also sees it as an early, handcrafted, analog version of the kind of predictive text we now find in Google autocompletes and advanced smartphone keyboards. "Predictive text of that sort was already baked into Chinese typewriters in the mechanical realm, and then gets brought into the realm of Chinese computing in the '60s and '70s.” Nowadays, he said, in China, pretty much every interaction a person has with a computer interface — from word processors to search bars — has predictive text built in.

These days, the QWERTY keyboard is standard in China — but instead of each key corresponding to a single letter in the alphabet, each key corresponds to a sound, and predictive text suggests a character that goes with those sounds. As a result, he said, after decades of relying on slower technologies, "the fastest Chinese computer inputter using a QWERTY keyboard input ... is faster than the fastest alphabetic typist.”

Both alphabetic and Chinese typewriters had an indelible impact on the way we communicate today, but only the Chinese typewriter has been almost entirely forgotten. Only a few institutions in the United States, including the Huntington Library and the Museum of Chinese in America, have Chinese typewriters, and three Chinese speakers I spoke with about this article weren’t aware they had ever existed.

So Mullaney, who amassed one of the largest collections in the world more or less by accident, is trying to “Save the Chinese Typewriter," starting with a (successful) Kickstarter campaign. His first Chinese typewriter, which is seafoam green and was the leading model in China throughout the 1970s, was given to him by a man who worked at a church in San Francisco. The typewriter had been used to print Chinese-language bulletins, but its services were no longer needed, and the man didn’t know what to do with it.

“If these were Western typewriters, you’d have the pick of the litter in terms of where to donate a machine like this or sell it on the antique market,” Mullaney told BuzzFeed News on a hot afternoon outside on Stanford’s campus, where he is a history professor. “There’s no such thing for East Asian information technology and Chinese typewriters.”

In the end, Mullaney's Kickstarter campaign raised more than $13,491, and his traveling exhibition will — “outside of maybe the National Library of China and the National Diet Library in Japan” — feature more Chinese typewriters than any other collection in the world. The tour kicks off with an exhibition in the San Francisco Airport in 2017.