The men of Magic Mike get off on getting women off. That was a narrative strain of the first film, Magic Mike, but in the sequel, Magic Mike XXL, the sublimated becomes the sublime. If Magic Mike is a film about the business of stripping, with masculine, capitalistic struggles at its center, then XXL is a story about the strippers themselves, and how they’ve come to understand their place in the world. It's a place in which consent is hot, erotics are fluid, and nothing is as powerful as fulfilling a woman’s desires: physical and emotional.

Magic Mike XXL thus conceives of pleasure, and eroticism, as a force with many vectors. Most media represents desire almost exclusively as something that occurs between traditionally attractive, straight, appropriately sculpted white people under the age of 37, yet XXL shows it passing between races, between body sizes, between ages. Black women, middle-aged women, plus-size women, young women: We see all of them aroused. Sometimes they’re frenzied; other times they’re bashful. But in the spaces of the film, just like the space of the cinema in which the film is screened, that appetite isn’t just normalized, but encouraged.

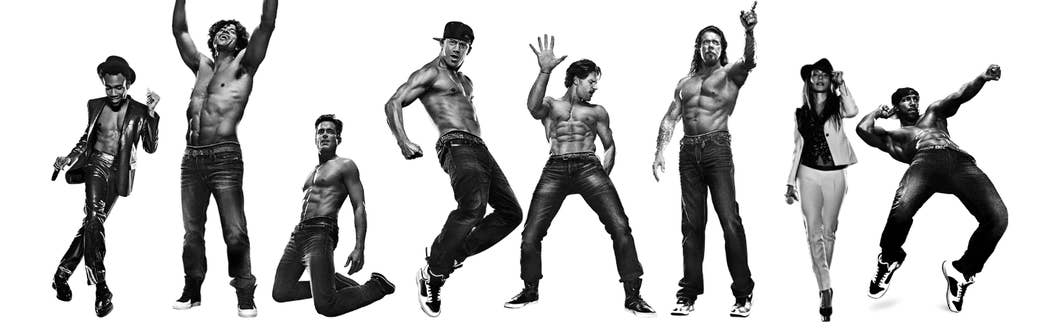

It’s difficult to tell if the men of Magic Mike XXL are likable because they strip, or if the particular type of stripping displayed in the film — with attention and joy and delight in the movement of the body and the way that women react to it — attracts a certain type of man. Either way, these men — Mike (Channing Tatum), Richie (Joe Manganiello), Tarzan (Kevin Nash), Ken (Matt Bomer), and Tito (Adam Rodriguez) — aren’t homophobes, racists, misogynists, or assholes.

The one moment of one-upmanship happens when the men attempt to display their prowess at non-stripper jobs, which are limited, unoriginal, or struggling.

They’re bad at business; their muscles are for looks, not labor. All the costumes they used to wear — the fireman, the Navy sailor, the Ken doll — were for an old-fashioned mode of masculinity with which they’ve never identified. When Channing Tatum points out that Joe Manganiello, whose old act was rooted in the performance of a fireman, is terrified of fire, it takes a hit of Molly for Manganiello to get honest enough with himself to let it go. But when he does, he articulates the crux of this particular group of men’s identity: “I’m not a fireman!” he joyfully exclaims. “I’m a fucking male entertainer!”

The men’s peace with their place in the post-industrial world is what makes them so incredibly, irresistibly watchable. Instead of acting out against the supposed decline of the American male — the theme of basically every show on extended cable for the last decade — they embrace a new definition, one that doesn’t resort to violence, sexual or otherwise, or homophobia, in order to fortify an old-fashioned sense of manhood.

Instead, they create new, fluid forms of masculinity — the type of masculinity that likes to attend a drag show not as a joke, but for actual pleasure, that feels no need to undercut homoerotic tension with declarative displays of heterosexuality. Unlike the boys of Entourage, who sit as far apart as possible in their convertible, gazing out at possible conquests, the men of Magic Mike XXL squeeze in close, reveling in one another’s company. They don’t have big dick contests because everyone knows their dicks are big enough.

This point is beautifully underlined by each stop on the crew’s picaresque journey through the South. At each stop, they learn and/or demonstrate a new understanding of female desire. In Savannah, Georgia, they show up at the door of a strip club called Domina, where Mike reunites with Rome (Jada Pinkett Smith), the most formidable — and fascinating — presence in the film. Rome owns her own mansion-like club, employs her own dancers, and limits access to the club via a members-only list: a list that, if looks are to believed, is made up exclusively of black women. It's a locus of black female desire and satisfaction unlike any I’ve witnessed in mainstream film.

Ostensibly, Rome is a replacement for Matthew McConaughey's Dallas — and the role was originally written for a man. But look at those names: Rome is infused with the knowledge of its centrality in the history of mankind; Dallas is central to, well, Texas. Rome wears menswear; she calls Mike on his shit; she has a castle filled with royalty — “my queens.” She makes Dallas look like a broken-down joke of a man.

When Rome shows Mike’s team what Domina has to offer, they witness performances that rival, if not entirely eclipse, their own. In any other film, the two groups of men would become enemies, yet in Magic Mike XXL, we watch Mike’s crew watch the dancing in wonder and appreciation. Rome eventually compels Mike to take the dance floor, but it’s not intended as a dance-off so much as a reintroduction. Afterward, the camera pans the two groups as they pair off and chat. They’re learning from one another. It’s fucking beautiful.

Scenes from Domina

Competing with one another matters less, after all, than pleasing women. The first film showed that these men knew how to please women through physical suggestion, but XXL shows them incorporating the mental component as well — most of which they learn from Rome and the men she’s helped train. Rome understands, for example, that a shy, meek looking woman in the corner of the room might need something different than dry-humping, and brings her to Andre (Donald Glover), who creates a song that makes her feel worthy and lovable. That might not be orgasmworthy, but it’s fulfilling one of the myriad purposes for which women seek out these experiences.

Same for their next stop, at a plantation filled with middle-aged Southern belles. At first, the scene threatens to devolve into a joke with a bunch of over-the-hill cougars, led by Nancy (Andie MacDowell), as the punchline. But it’s saved by a truly moving interaction between one of Nancy’s friends, Mae, and Ken. When Mae admits that her husband has never had sex with her with the lights on, Ken’s reaction is immediate and sincere: “Tell him what your fantasy is, and then tell him to do it with the lights on.” He asks for a memory that she loves from their relationship, and when she mentions a song, he sings it to her. And when Nancy bemoans that she’s only had “one penis my entire fucking life," Richie fulfills that lack — only instead of watching MacDowell, post-coitus, amazed that a hot young man would want her, we see Richie, giddy as a schoolboy, exclaim that he’s finally found “his glass slipper." The entire mansion interlude suggests that listening — and then fulfilling the fantasy that your partner envisions — is incredibly hot.

When the crew’s journey culminates at the stripper convention in Myrtle Beach, they’re joined by Rome, Andre, and her top male dancer, Malik (Stephen Boss). Their performance works as palimpsest of their accumulated knowledge about female desire. The hokey group choreography, like the clichéd costumes, and Dallas’s über-masculine narration, are gone; in their place, a series of performances that turn on basically every component of the straight female body. Tarzan plays an artist who can show a woman just how beautiful she looks in his eyes; Tito does demonstrative things with sweet treats. Ken sings D’Angelo’s “How Does It Feel,” whose lyrics plaintively declare “Girl it’s only you / Have it your way” before asking, repeatedly, to know exactly how does it feel. Richie enacts a scenario of storybook romance paired with a performance of 50 Shades–level fucking. Mike and Malik offer something akin to highly choreographed group sex.

Various scenarios of female satisfaction, fulfilled

And all of it is guided by Rome’s commentary: “What is a ‘good woman'?” she asks her crowd. “Sometimes you just want a guy to ask what you want and give it to you just. like. that.” Some women love the emotional tension and release that comes with an elaborate scenario and its fulfillment; those same women can also appreciate a good ravaging. Their performance doesn’t attempt to entertain one way for good girls and another for bad, one way for virgins and another for sluts. They don’t delineate or judge women by their level of desire. They just try to fulfill it.

How did a sequel become both simpler and smarter than the film that came before it? I want to attribute it to Channing Tatum, the star and executive producer who’s not only demonstrated his own fluid conception of sexuality, desire, and masculinity, but refuses to take himself seriously. He’s People’s "Sexiest Man Alive," but he also laughs, riotously, at the scaffolding of his own celebrity, and his images consolidates all of the joy, confidence, and endearingness that lives in the heart of Magic Mike XXL. He’s a total nouveau bro. And if he has anything to do with the future of Hollywood, there’s hope, however tentative, for a genre of blockbuster filmmaking that doesn’t conceive of women simply as objects of desire, but capable of it themselves. It’s crucial for female filmmakers, producers, and stars of various sexualities to continue to shape these depictions. But how beautiful, and surprising, that a man like Tatum would help lead the way.