A rare "super blue blood moon" is coming early Wednesday morning, and will be visible across most of the US.

So what does this mean, exactly?

“This is actually a trifecta of lunar phenomena,” Renee Weber, a planetary scientist at NASA, told BuzzFeed News. “We get the supermoon, we get the blue moon, and on top of that we get a lunar eclipse, which is the blood moon.”

The last time these three things happened at once was on Dec. 30, 1982, and the next one will be on Jan. 31, 2027.

A supermoon is when a full moon occurs as close as possible to Earth.

The moon’s orbit around the Earth isn’t a perfect circle — it’s elliptical. This means the moon isn’t a fixed distance away from our planet. At its nearest point to Earth, the moon is 14% closer than at its farthest point.

In scientific terms, a full moon at its closest point is called its “perigee” and at its farthest point is called its “apogee.”

“I think it will look cool, but supermoon just means it’s fractionally closer than average,” Weber said. “If you didn’t have context, you wouldn’t notice it.”

If there are two full moons in the same month, that second one is called a “blue moon.”

There was a full moon on Jan. 1, 2018. The second one is on Tuesday night, Jan. 30, and will be visible into early Wednesday morning. It doesn’t happen very often that the human calendar and the lunar calendar sync up like this, leading to the phrase “once in a blue moon.”

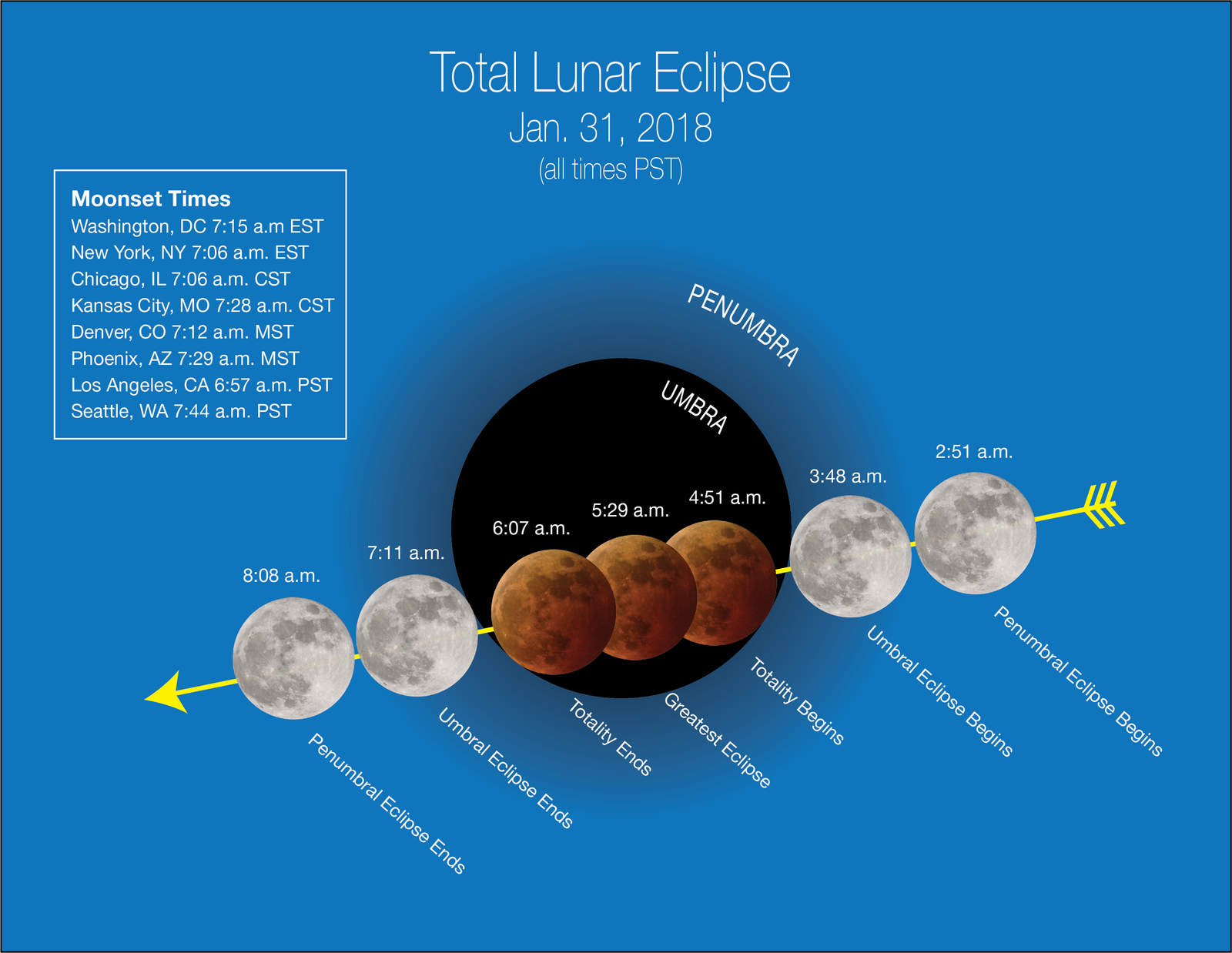

A “blood moon” — the main event — is when there’s a lunar eclipse. The western half of the US and Hawaii will have good views of the total lunar eclipse. The East Coast isn’t so lucky.

A lunar eclipse is when the moon, Earth, and sun are aligned. Once the partial eclipse starts, the full moon will look as if it is getting eaten by a dark shadow. You’ll be able to see this part all across the country.

As totality approaches, the remaining sliver of the moon will turn red. And at totality, the full moon, now red, will come back into view. Even though there’s no sunlight directly hitting the moon, the moon will brighten because some light that’s traveled through the Earth’s atmosphere is reflected by the moon.

If you’re in New York City, Washington, DC, or anywhere else on Eastern Standard Time, you might catch the start of the eclipse in the early morning when the moon is still above the horizon and the sky is dark. But as the eclipse progresses, the moon will dip below the horizon, out of view, and the sun will rise.

From western Kentucky over to Hawaii, the total eclipse will be visible (assuming the skies are clear of clouds or fog). To find out if and when the partial and total eclipse will be visible where you live, check out this website. BuzzFeed News will also be livestreaming the event Wednesday morning, 7:30 to 9:30 a.m. ET, on its Science Facebook page.

How red the moon looks is partly influenced by recent volcanic activity.

The fully eclipsed moon is lit up entirely by sunlight passing through the Earth’s atmosphere and getting scattered. The more gas molecules and particles in the atmosphere, including volcanic ash, the more light scatters. The blue end of the spectrum scatters first, leaving behind only red.

Due to lower-than-average volcanic activity last year, this eclipsed moon may look brighter and less red than in past years.

The total lunar eclipse will last up to 1 hour and 16 minutes, depending on where you are.

That’s much longer than a solar eclipse. During the "Great American Eclipse," which occurred in August 2017, totality lasted up to 2 minutes and 40 seconds.

Unlike the solar eclipse, it’s totally safe to look at the lunar eclipse without any special glasses or tools.

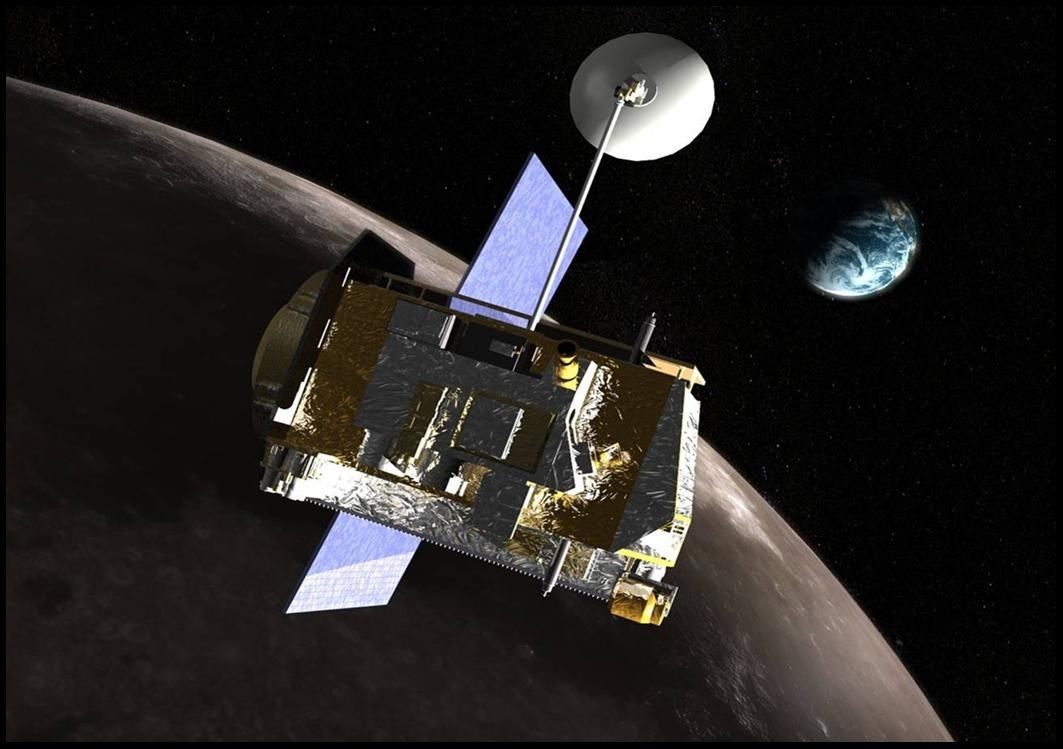

The “Lunar Reconnaissance” satellite will be tracking the moon’s heat during the eclipse.

On the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, a satellite circling the moon, there is equipment monitoring the thermal signature of rocks and other surface features. During the solar eclipse, the section of the Earth that was in the path of totality cooled down by a few degrees.

“Same thing happens on the moon,” NASA’s Weber said. “Instead of a couple degrees cooler, it feels a couple hundred of degrees cooler.” This means that rocky features — such as certain impact craters “that may normally get washed out” when the moon warms or cools during its normal cycle — may show up more clearly during this event, Weber explained.