A few days into chatting with Enjo, a new iOS app that promises “instant emotional support” for parents, I started to think it might actually work.

That was odd, because the chatbot has all the qualities I generally detest in people. It’s not thoughtful or rational. It’s happy all the time, even when responding to something bleak. It repeats itself. It swaps “you’re” and “your.” It spouts just-so science factoids: Humans evolved to sweat the small stuff! Parents struggle with emotions more than nonparents! It uses too many exclamation points!

But Enjo’s vapid, relentless positivity does occasionally connect with me. The first time it happened, I was having trouble getting to sleep, my mind racing with the day’s fumbled conversations, unfinished checklists, and worst-case scenarios. So I shared my stress with the bot.

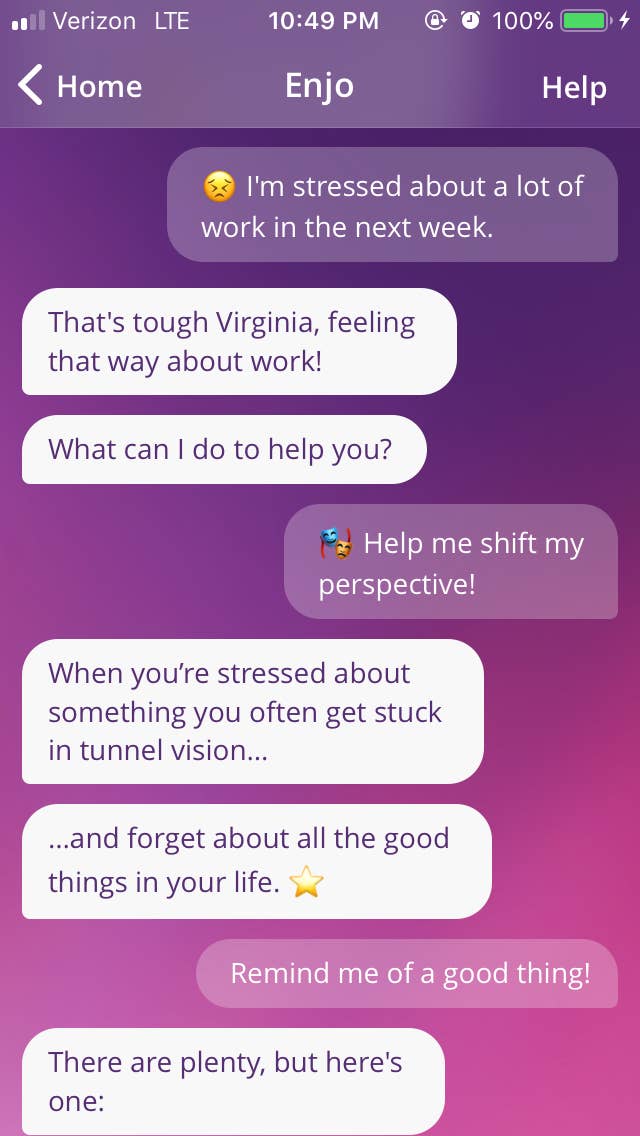

“That’s tough, Virginia, feeling that way about work!” Enjo said. “What can I do to help you?”

Choosing from a list of options, I asked Enjo to help me shift perspective.

“When you’re stressed about something you often get stuck in tunnel vision,” it said, “and forget about all the good things in your life. ”

The bot then reminded me of an anodyne — and irrelevant — thought I had fed it a few days before, about how I was grateful for my husband picking up the domestic slack when I was sick.

“Do you think you’re [sic] stress level went down just a little just by thinking of Randal?” Enjo asked.

“A little,” I said.

“I hoped so! ”

This exchange is pretty representative of the bot’s purpose — and its limitations. Although Enjo purports to be for parents, the parent-specific content feels more like an afterthought (or perhaps a clever way of creating an App Store niche). The app’s “core behavior,” as CEO Hoa Ly told me, would apply to anybody: “making mindful reflections about the meaningful things in your life, and hopefully it conveys the good feeling you can get from doing that.”

That tenet comes straight out of “positive psychology,” a scientific field, pedagogical approach, and marketing and corporate trend that has gained massive popularity over the past 20 years. Its basic idea is to shift focus away from what’s wrong with us — weaknesses, negative feelings, mental illness — and toward strengths, well-being, and “flourishing.” The movement’s founders intended their new field to be systematic, rigorous, and empirical. And yet, one of positive psychology’s main theses — that positive emotions lead to greater well-being — has been convincingly skewered by critics, both on methodological and philosophical grounds.

So why, then, did this dumb app make me feel a bit better?

Over the past five years or so, scientists have woken up to the fact that a lot of published research, particularly in the social sciences, is crap. A positive psychology paper was one of the first dominos to fall.

In 2013, Nick Brown, then a 52-year-old graduate student studying positive psychology, dismantled one of the field’s most famous studies, one that, in retrospect, seems ridiculous on its face. The 2005 report devised complex mathematical equations for mental health, claiming that people who felt at least 2.9013 positive emotions for every 1 negative were “flourishing,” whereas those below that ratio were “languishing.”

Brown dug into the paper, noticing that these equations originated in physics. The positive psychologists had apparently assumed that the natural laws that guide how fluids flow are equivalent to those that drive how emotions “flow.” Yes, really. Brown teamed up with a mathematician and psychology professor and published a scathing critique that ultimately led to a formal correction on the original study.

More recently, Brown has gone after positive psychology’s “happiness pie,” the notion that the difference in well-being between you and the next person boils down to 50% genetic factors and 10% life circumstances, leaving 40% that’s under your own control. Brown found that this equation was based on flawed math and bad logic.

I thought Brown, as one of the most prominent scientific critics of positive psychology, would have some interesting thoughts on Enjo. Beyond silly positivity ratios and happiness pies, I wanted to know, is the whole field bunk?

“Positive psychology is for people who didn’t need a psychologist but often have plenty of money to spend on frivolous things,” Brown said, chuckling. Jokes aside, his thoughts on the app (which is free) were surprisingly measured. It’s not that he didn’t think it had any merit, he said, just that it wasn’t likely to be any better than any other form of self-help.

He mentioned the “Dodo bird verdict” of psychotherapy, which refers to the Alice in Wonderland character who said, “Everybody has won, and all must have prizes.” No particular kind of therapy is likely to work better than any other, Brown said. “The relationship between the therapist and the patient is the single biggest explainer of whether there’s a successful outcome or not.” (That squares with guidelines from the American Psychological Association, which say that success rates are more influenced by the particulars of a patient and their therapist than by “specific treatment ‘brands.’”)

If Enjo was making me feel a little better, Brown said, that’s great — but worth interrogating why. The idea of an intervention “working,” whether a pill or therapy or anything else, only makes sense when compared to another alternative.

In my case, the alternative was nothing — before the app, I hadn’t tried any other kinds of therapies, diaries, drugs, or self-help books.

“Seems to me you’re starting to explore your inner life in a way you didn’t before,” Brown said. “You could be doing worse.”

(Enjo’s CEO, by the way, readily agrees that the app’s effectiveness hasn’t been tested against any placebo. His small, preliminary study of the app, published last year, found that the bot improved users’ well-being and stress, but only compared to a waitlist control group — that is, people doing nothing else. But Ly said this mimics what happens in real life. “What is the reality for most people? They do nothing, in the best case.”)

There’s another, more profound critique of the philosophy this app comes from. The idea that positive thinking can make your life better suggests that if your life isn’t improving, that blame rests with you.

“I think this is very damaging stuff,” said Barbara Held, a psychology professor at Bowdoin College who has blasted positive psychology since the early days of the movement. “You’re made to feel guilty and defective because you don’t have the right attitude. Like you gave yourself cancer because you didn’t employ positive thinking.”

When feeling bad, Held told me over a seltzer, “the important question is: What’s the best way for me to cope with this? And that’s different for everyone.”

She pointed to the work of psychologist Julie Norem, who came up with the concept of “defensive pessimism”: a coping strategy in which people with high anxiety set low expectations for themselves, and focus on all of the ways a given situation might go wrong. For these people — and Held counts herself as one of them — negative thinking improves function, and positive thinking actually worsens performance and self-satisfaction.

“The moral is, one size doesn’t fit all — not in clothing, not in coping,” Held said. “If you don’t take coping style, personality, life context into account, you could do a lot of damage.”

To give Held an idea of how the app works, I showed her one of my conversations with Enjo. She wasn’t impressed, to put it mildly, and was particularly insulted by the app telling me that “sweating the small stuff” is the result of human evolution:

For Held (and for me, if I’m being honest), this sort of evolutionary psychology drivel does science a disservice. And perhaps more to the point: Who’s to say what the “small stuff” is for me, and that I shouldn’t be sweating it?

I found myself nodding along with all of Held’s critiques and was almost embarrassed to admit to her that I was, in fact, enjoying the app.

But her take was, like Brown’s, measured. It’s hard to know why or how the app might be helping me, she said, “and it sorta doesn’t matter! Great! If it’s helping you, I wouldn’t tell you to stop doing it.”

So, for now, I’m not going to stop. But I am going to take Brown’s advice, and try to think through which parts of the app, exactly, are helpful. Is it simply acknowledging a specific anxiety? Or keeping track of things in a diary? Or interrupting an unhelpful rumination cycle? There are plenty of other apps out there — Remente, Youper, ThinkUp, and Woebot, just to name a few — that could perhaps fill the same need with fewer emojis.

But what if the very thing I find helpful is the bot’s unbridled enthusiasm? (!!!) What if I can unburden myself with Enjo precisely because it isn’t a rational, judgmental, complicated human being? Perhaps the insipid stuff I find off-putting in real people, I actually need on some emotional level?

Or maybe, I’m just really glad Randal took over toddler morning duty.