Chelsy knew something was seriously wrong with her health after she suddenly fell asleep while driving with her infant daughter in the backseat. It was her first major narcoleptic event — she was in her mid-twenties — and “it was absolutely the most terrifying moment in my whole life,” she said. By chance, she was at a stoplight, her foot stayed on the brake, and no one was hurt. She awoke to a cacophony of horns, and “I absolutely lost my mind.”

She underwent a long succession of tests. Chelsy was diagnosed with a number of conditions: episodic sleep disorder, insomnia, chronic fatigue, and fibromyalgia. She continued to feel terrible. It took more than a year before she was diagnosed with primary immunodeficiency disorder, a genetic condition that weakens the immune system. Her daughter, who also experienced some health challenges, had it as well. They both saw their conditions progress to common variable immune deficiency (CVID).

Her illness eventually made it impossible for Chelsy to work full time. She missed 70 of the 200 days she had been scheduled to work at a childcare center because she kept getting sick. Bronchitis would turn into pneumonia. One cold bled into the next. “That’s the thing about immune deficiencies. You almost never get just one infection,” she said. “You start out with something, some catalyzing event. It can be as simple as just having allergies. Then because your body is weakened … opportunistic infections take hold in other areas, or just kind of piggyback or bloom, and your body absolutely has nothing to fight it with.”

Chelsy confronted the difficult reality that at age 30, she was very sick, and it would impact her ability to work. And “I started realizing how incredibly the odds were stacked against me,” she said, “by no fault or choosing of my own.” Not only did she have to learn how to tackle life with these medical disorders, she also had to tackle America's benefits system, which would prove to be just as much of a battle.

“I really feel so strongly that if anybody who had to walk in my shoes — to be in my 20s with a child and imagine all of the great, amazing life I thought I had ahead of me, and then suddenly find out, no, I'm really sick, and I'm not ever getting better, ever; I'm going to progressively get worse, and my health will diminish little by little until I'm a shell of a person or dead, whichever comes first. If people had to go through that or if that were a reality that a lot of people had to witness, I don't think most people would be so crass,” she said in an interview with BuzzFeed News.

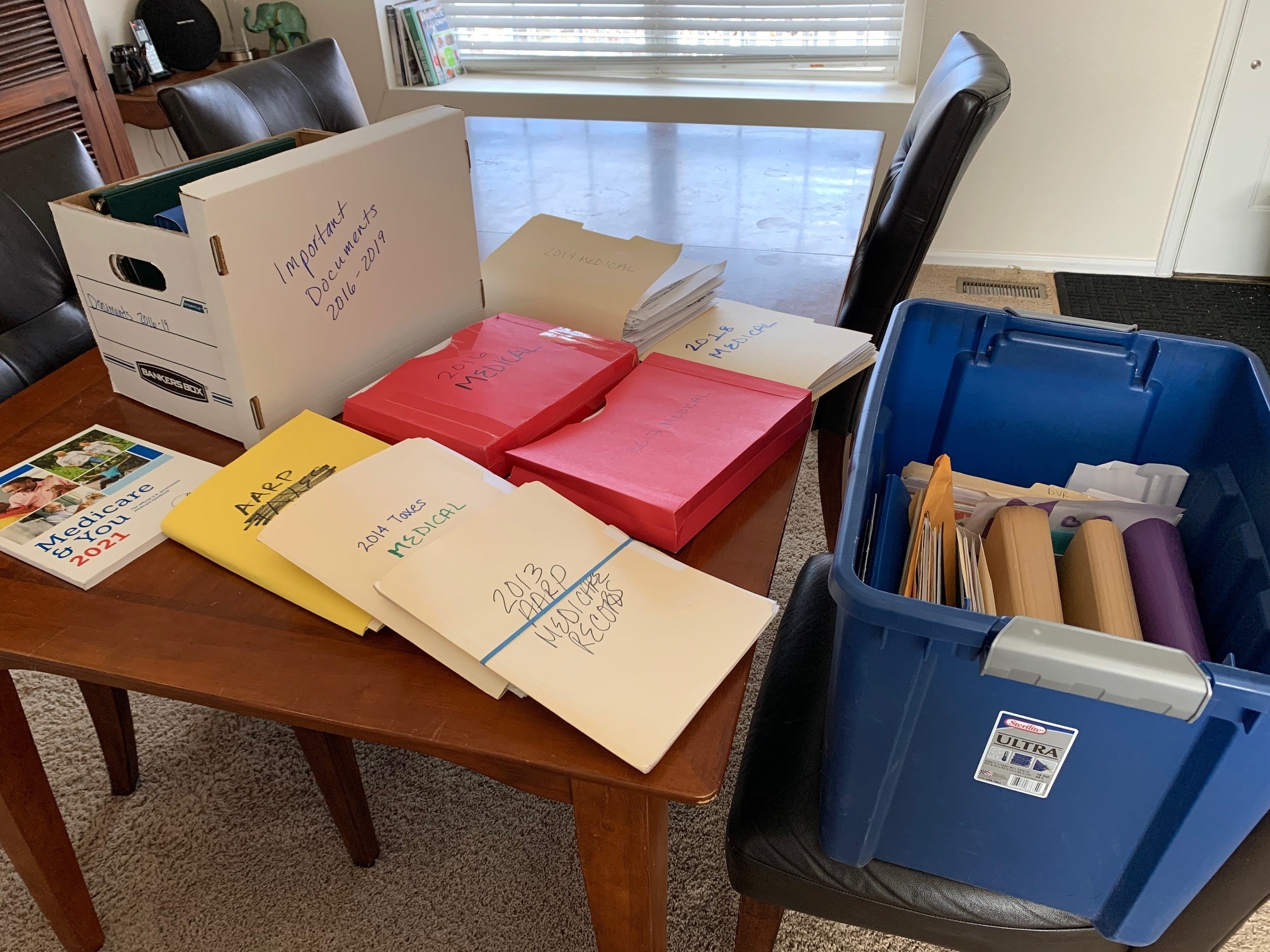

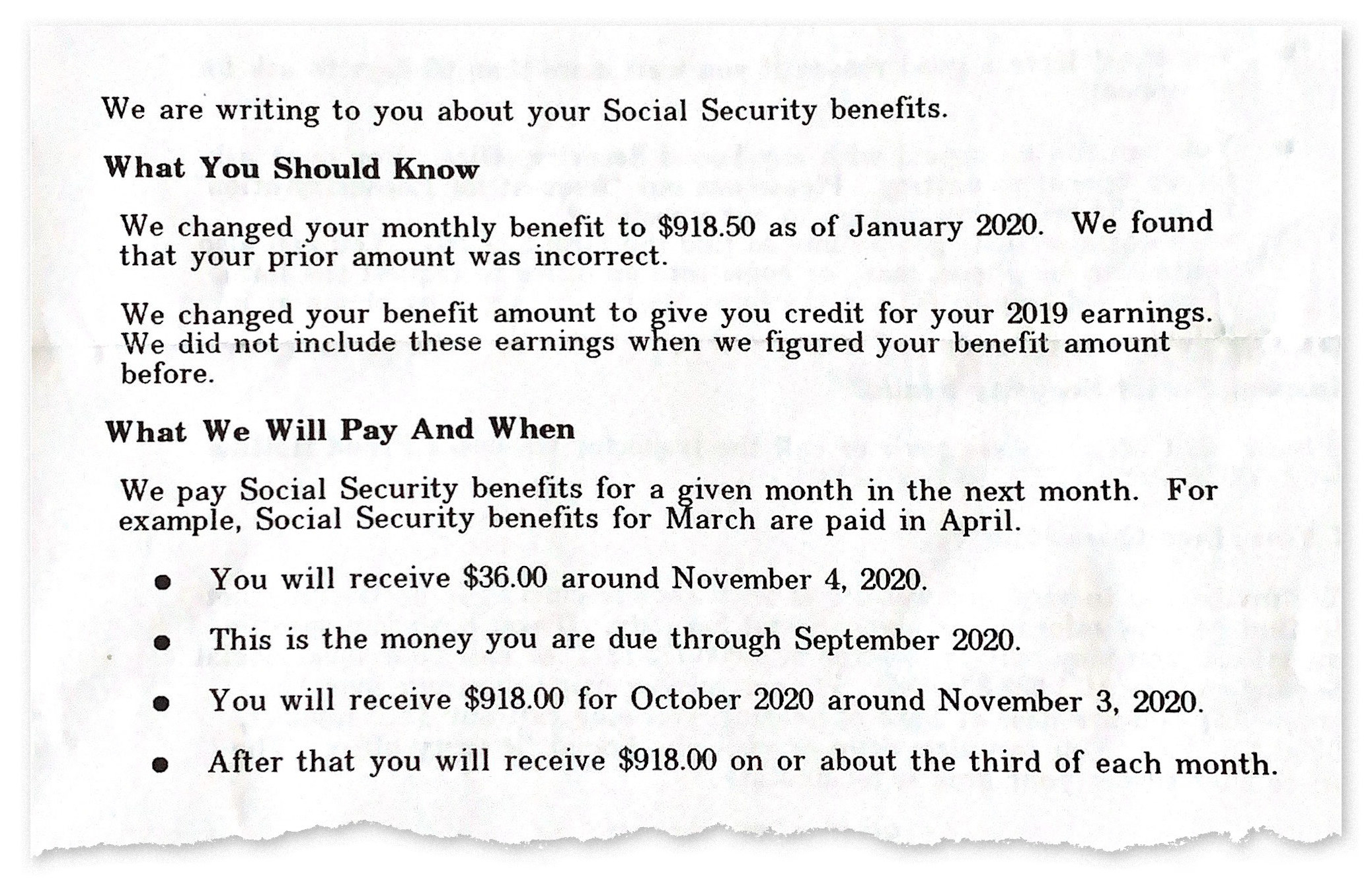

Getting help was a long fight, and when it finally came, it wasn’t enough. It took more than a year for her to win approval for disability benefits from the Social Security Administration, which manages the program. Even then, her and her daughter’s combined benefit each month was less than $1,000, so she needed to find a way to supplement her benefits with extra income, especially after she and her husband divorced.

She found part-time work at a contract post office run from a quiet hardware store outside of Denver and freelanced as a journalist. The post office paid close to minimum wage, offered no benefits, and she still got sick — a lot — but her boss understood her medical needs, and the job filled the gap where the disability checks fell short, allowing her to buy medicine, groceries, and gas. She got engaged again; they bought a house. “It’s not like I've ever drawn my disability check, and then just kicked my feet up,” she said. “But my body can only do so much, and it will only ever be able to do so much.” For the last seven years, Chelsy and her daughter got by this way, if barely.

Then the coronavirus arrived.

Chelsy, now 41, left her job at the post office for her family’s safety, but the result has been financially devastating. She is ineligible for unemployment benefits, despite losing her job, because she receives disability benefits, she learned from a local Social Security office near Denver. (The requirements for the two programs are at odds with each other: To collect disability benefits, a person must be unable to work; to collect unemployment benefits, a person must be ready and willing to work.) Her freelance work dried up. Her search for employment that would allow her to stay home, so far, has gone nowhere. By September, the $3,000 Chelsy had in savings at the start of the year was entirely gone. And in November, her ex-husband, who pays a “small, but helpful” amount of child support every month, lost his job.

The country’s disability safety net was never adequate to support many of the people who rely on it, and throughout the pandemic, it has failed those like Chelsy who are now unable to find ways to make up the shortfall. She still has medical expenses to pay. Chelsy said while the government’s Social Security Disability Insurance provides necessary aid, it was never possible to survive on it alone, making it hard for recipients like her to get by if they lose their supplementary earnings.

“I've done essentially everything, adjusted every knob and dial to try and maximize and make our finances work as best as possible, and trimmed every bit of fat. And as of last month, I am officially out of money,” she said. “I have nothing left for the rest of the year.”

Social Security offices have been closed since March, which disability experts say has caused applications from people who need help to plummet. Unemployment remains high. There’s little else Chelsy can do until the country’s crises are under control. “In the short term, I need money. But I can't go back to my job at the post office without risking not only my life, but my daughter's life. That's just 100% not a risk I'm willing to take.”

The SSDI program “doesn’t provide the kind of protection or opportunities that we would hope,” said Pennsylvania Sen. Bob Casey in an interview with BuzzFeed News. Casey has proposed various legislation to increase support for people with disabilities. “There's no question that there are a mountain of people that, in many cases, are and could fall through the cracks because of the economic impact of the pandemic.”

Chelsy’s fiancé is picking up more of the bills now, but without her extra earnings from work or unemployment benefits, the numbers aren’t working out. They’ve listed their possessions for sale online. They’re talking about selling the house now.

When Chelsy thinks of America’s disability system, she said, “In my mind, I imagine it like being on a trapeze. We’re all on a trapeze and we believe that disability or unemployment or things like that are a safety net that’s just underneath us. We all pay into it, and we can access it when we need. But the net is not as high as we think; it’s not going to cushion us well before we hit the ground. It’s situated just 6 inches off of the ground. So when you land in that, you’re pretty much already there. And it is going to hurt when you fall into it.”

In 2019, disability benefits were paid to almost 10 million people, according to the Social Security Administration. About 38% of recipients earned less than $1,000 per month and about 1 in 4 were living in poverty. Many are very sick: The leading reason recipients exit the program within the first few years of getting their benefits is not that they return to work; it is, sadly, death.

Disability benefits in the US are hard to get and hard to live on — unlike prevailing stereotypes about the program — and they have been at risk of being further tightened.

Overall, only about one-third of all disability applicants are approved. With the average monthly benefit at $1,258, recipients quickly find that the program is really designed to only provide “partial wage replacement,” said Kathleen Romig, a senior policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and a former policy analyst at the SSA.

If an applicant appeals an initial denial (3 out of 4 initial applications are denied), the wait for a final decision from the court is long — for many, too long. From 2008 through 2019, nearly 110,000 people died before receiving a decision about their appeal, according to the Government Accountability Office. From 2014 to 2019, 48,000 people filed for bankruptcy awaiting a decision. The waiting doesn’t end there. After an application is approved, there is a five-month “waiting period” starting from when the SSA determines the disability began, for which a person does not collect any benefits. There is also a 24-month waiting period from the start of SSDI payments to get Medicare.

A survey by Allsup, a company that helps people navigate the SSDI system, found that during this long process, people’s “disability gets worse; they lose their health care coverage from their employer; they deplete their 401(k) and retirement funds; they borrow money from their family; and their incidence of depression and anxiety increases, which complicates their disability,” said Mary Dale Walters, a senior vice president for Allsup.

The pandemic has created an urgent need to reevaluate these wait times, said Casey, who is trying to eliminate this requirement. “When they put in waiting periods, they were designed to save on costs. But when you’re in the middle of this kind of public health emergency, and all the economic trauma that comes from it, it doesn’t make a lot of sense,” he said.

Chelsy knows all too well what it’s like to wait. In 2009, she applied for disability immediately after leaving her job at the childcare center. Her initial application was denied. She appealed, and it took a year and a half and the help of a lawyer before an administrative law judge granted her approval during a roughly 15-minute hearing.

“This was after hours of me calling and dealing with Social Security. This is after years of my health crisis unfolding, and then I get 15 minutes in front of a judge — I cried the entire time. The judge asked me, ‘Why are you crying?’ And I couldn’t even articulate how desperate I was, how scared I was that he was going to deny me, and how much was riding on it,” Chelsy said. “Fifteen minutes changed my whole life. And it felt like the most arbitrary and ridiculous process ever once it was done.”

She’s come to the conclusion that the rules for disability “aren’t written to really help anyone” in normal times, let alone during a pandemic, she said. About 44% of younger disability recipients are near or below poverty, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. One factor is a person’s monthly payment is calculated based on their earnings before receiving disability. People like Chelsy who began collecting at a relatively young age, when their earnings were low, may only be entitled to a small and unlivable benefit amount.

Chelsy’s monthly disability check was roughly $700 per month after paying for Medicare, and her daughter received about $100. Even with Medicare, she was paying $80 per month for just one of the eight medications she takes every day, she said.

Chelsy needed to earn extra income, but she couldn’t make too much. There is a cap on how much a recipient can earn from work if they want to continue collecting disability benefits — in 2020, benefits stop if a recipient earns more than $1,260 a month from work, and the limit can be lower based on a person’s benefit amount. So “even if they’re working, they’re really economically vulnerable,” Romig said.

This is the paradox of SSDI: Applicants must prove they are unable to work in order to get disability benefits, but once they are approved, the system is set up to try to get them back to work again. In this way, it functions as more of a “short-term safety net,” said Allsup’s Walters.

Yet the majority of applicants, who are denied, never even land in this safety net, and “the fact is, most of them are pretty sick,” said Romig. “They might not meet the criteria, but they're not doing that great and they're not able to work very much and they really suffer. They have a hard time financially and medically.”

In 2020, nearly a decade after first being approved for SSDI, Chelsy and her daughter’s combined monthly disability benefits are about $975. The cost-of-living adjustment to her benefit over the years has been infinitesimal. Her fiancé added her to his health insurance so she would no longer have to buy Medicare.

Chelsy dreams of things she can do to get out of the disability system, to make enough money to support herself: land a book deal, secure lots of freelance work. “I would give anything to not be part of the Social Security disability program. Anything,” she said. But for her, every day feels like having a flu that won’t end: body aches, weakness, headaches. Her body can’t work full time, not for long. Chelsy grew quiet. “I can’t physically do more. That was a really hard and very bitter pill to swallow because this whole situation happened when I was so young. I didn't really have the opportunity to go and try. I had just graduated from college when I started getting sick. And so, I get emotional because I want to be hopeful that yes, someday, I will not need [disability benefits]. But with each passing year that my body struggles more and more, I feel like it becomes less and less of a possibility. I have to ask myself, I'm 41 years old, what is it going to look like in 10 years or 20 years? That’s the hardest thing for me to face: What does my future look like? I don’t really see a lot of of hope. There's no cure.”

As the third wave of the coronavirus spreads across the country and skyrockets in her home state of Colorado, Chelsy is keeping busy at home with the many responsibilities of parenthood and applying for jobs. She is trying to learn audiobook narration and podcasting as another potential source of income that would allow her to work from home. The recent wildfires in Colorado triggered her allergies, which led to a sinus and ear infection, and then developed into strep throat, which she treated with antibiotics.

Her teenage daughter has been out of school and largely stayed home during the pandemic, aside from a six- to eight-hour visit to the immunologist office every three weeks for immunoglobulin infusions, which cost $15,000 per treatment, paid for by insurance. They recently learned she will need these treatments for the rest of her life. “She and I were devastated,” Chelsy said. “I felt guilt and shame for cursing her with this broken immune system, and fear, because how will she function independently as an adult with this burden hanging over her head?”

The coronavirus precludes most aspects of their former life. Last May, her daughter was hospitalized with pneumonia, strep throat, and an upper respiratory infection. “She very nearly died,” Chelsy said. She survived but, like her mother, she is always at risk, and mitigating that risk is hard. She cannot, for example, have certain vaccinations for things like meningitis or HPV, which may cause infection. It’s not clear how risky it will be for them to get vaccinated whenever a product for COVID-19 might become available.

When the coronavirus first started spreading, Chelsy’s daughter “had a total breakdown. She’s like, I’ve never had a boyfriend. I’ve never had sex. I never got to graduate high school, or go to college, or get married, or have a job, or drive by myself. It really felt to her like the world was ending,” Chelsy recalled. “She had that break of spirit of, like, ‘Well, do I even care? I feel like I’m living on borrowed time anyway.’”

All Chelsy could do was try to pass onto her young daughter a sense of hope and strength, despite the unstoppable decline of her health, despite knowing there is no cure for their condition. “You just have to survive this in order to get to those things,” Chelsy told her. “Life happens all around us and there is beauty, even in the awful, even in the chaotic … There’s always the other side of it, and nothing is going to last forever. We just have to survive long enough to see that. What that takes is just continuing to have dreams, and have goals, and have aspirations, and not allow ourselves to be stripped of those things because things are hard, and because we're scared.” ●