Cecil Clayton was executed by lethal injection at 9:13 p.m. and pronounced dead at 9:21 p.m., the Missouri Department of Corrections said.

Missouri Attorney General Chris Koster, in a statement, said Clayton "paid the ultimate price" for killing a police officer in 1996.

“As one who has carried a badge for most of my adult life, I share the outrage of every Missourian at the murder of law enforcement officer, Deputy Christopher Castetter," Koster said. "Cecil Clayton tonight has paid the ultimate price for his terrible crime.”

Cecil Clayton's lawyer: "The world will not be a safer place because Mr. Clayton has been executed."

Missouri is set to execute Cecil Clayton on Tuesday for the 1996 murder of a police officer.

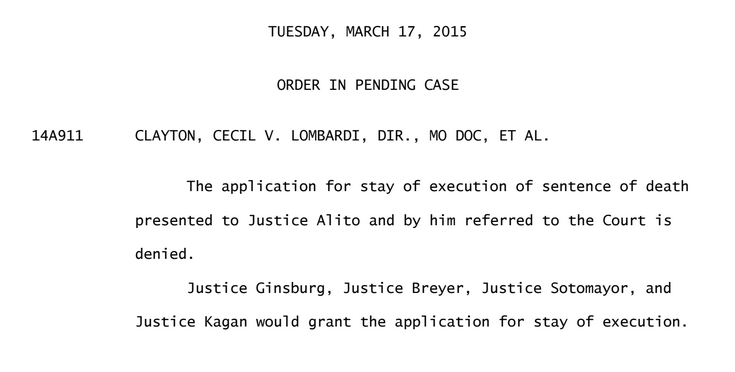

The Supreme Court denied a stay of execution to Cecil Clayton in all three requests. Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan would have granted the stay of execution in the request related to ongoing litigation over the state's lethal injection process.

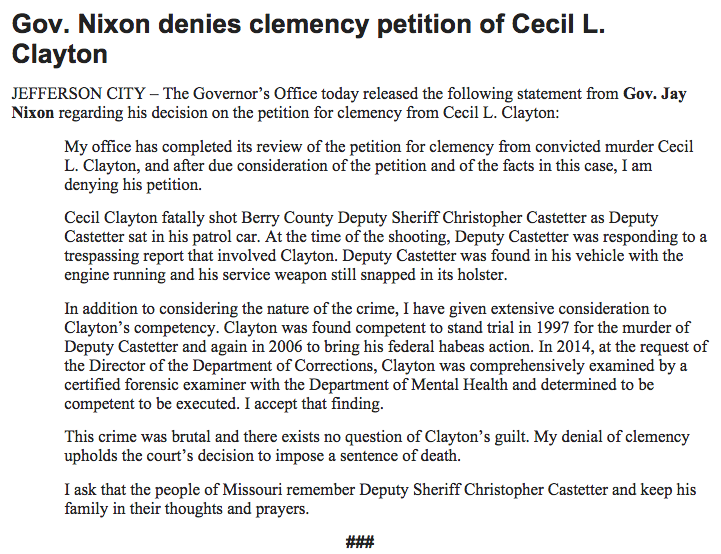

Update at 9:50 p.m.: Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon has denied Clayton's clemency request as well.

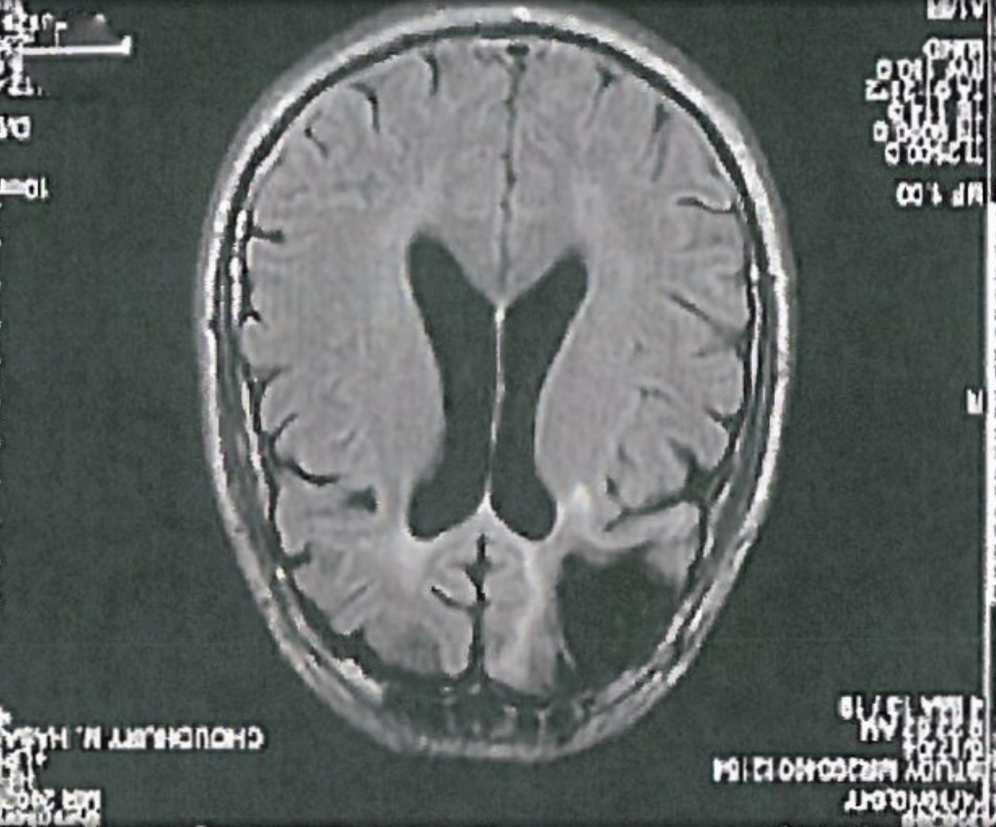

Clayton's lawyers asked the U.S. Supreme Court on Monday to stop his execution on the grounds that he is mentally incompetent to be executed because of a 1972 sawmill accident causing him to lose 20% of his frontal lobe in surgery.

The appeal said that Clayton, 74, suffers from severe mental illness, including dementia and the aftereffects of brain damage, and is intellectually disabled with an IQ of 71.

His lawyers argued that he has never had a hearing on his competency to be executed.

By a 4-3 vote on Saturday, the Missouri Supreme Court ruled that Clayton had not met "the substantial threshold" showing of incompetence required for a competency hearing.

In her dissent, Judge Laura Stith wrote that the court's decision to proceed with the execution violated the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment and that there were reasonable grounds to believe Clayton was intellectually disabled and entitled to a competency hearing.

[Update on Tuesday at 6:30 p.m. ET: Clayton's lawyers also filed a second stay request regarding ongoing litigation about the state's lethal injection procedures.]

[Update at 6:45 p.m. ET Tuesday: Missouri opposed both requests, first, the brain damage-related request and, second, the lethal injection process-related request.]

Clayton suffered from a traumatic brain injury at the age of 32 when a piece of wood shot out from the saw blade he was using and pierced his skull, embedding itself inside.

Doctors had to remove the embedded piece surgically causing Clayton to lose 7.7% of his brain, equaling 20% of his frontal lobe — which governs memory, judgement, impulse control, and social behavior, among others.

According to his lawyers, multiple medical evaluations over the decades have concluded that Clayton is constitutionally incompetent to be executed.

Clayton was "happily married" in Purdy, Mo., and had been sober for several years before the accident, his lawyers said. The brain injury "dramatically changed" his personality causing him to suffer from memory loss, hallucinations, and suicidal thoughts. He and his wife separated, after which Clayton abused alcohol, became depressed, and was prone to violent outbursts, according to his attorneys.

In 1978, a doctor determined that Clayton suffered from paranoid delusions and he was prescribed antipsychotic medications. In 1983, he was diagnosed with chronic brain syndrome, paranoia, schizophrenia, depression, and began receiving disability benefits. His lawyers said that his mental illness has deteriorated without treatment in prison.

Last month, a psychiatrist concluded that Clayton was incompetent to be executed due to his inability to understand the purpose of his pending execution. According to the report, Clayton was convinced he was "the victim of a conspiracy" and was engaged in "delusional denial that his execution will not take place relying on divine intervention in some form so he can pursue a gospel ministry as a preacher and sing with the best pianist in Missouri with whom he will tour the nation."

Missouri's statute says that a person sentenced to death cannot be executed if "as a result of mental disease or defect he lacks capacity to understand the nature and purpose of the punishment about to be imposed upon him ...."

Clayton's lawyers argued that Missouri lacked a constitutional method for determining competence to be executed.

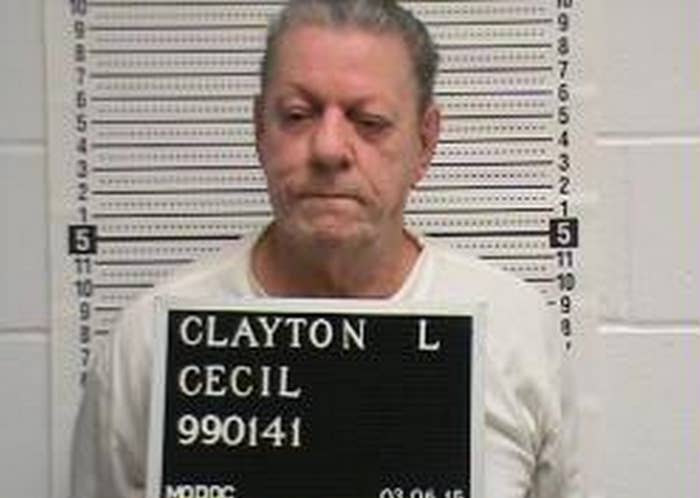

Clayton was sentenced to death for the 1996 murder of Missouri police officer Christopher Castetter.

After a fight with his girlfriend, Clayton was waiting outside her mother's house in November 1996, according to court documents. His girlfriend's sister called the police to report the suspicious vehicle she believed belonged to Clayton.

When Deputy Castetter drove up to the house, Clayton shot him in the head at point-blank range while the officer was still seat-belted in his patrol car with his gun holstered. Castetter, 29, who was married with three children, later died of a single gunshot wound to his head.

When asked if Castetter had done something to provoke him, Clayton told authorities, "He probably should have just stayed home. He shouldn't have smarted off to me."

Clayton was sentenced to death in 1997 after a jury convicted him of first degree murder.