Sometimes you gotta risk your life to survive, Jack says, and shrugs. He means we need to keep taking the subway: hope for the best, take precautions. We’re no car owners, and with the market skyrocketing like it has, that’s not changing anytime soon. We can’t afford cabs, either, which have gotten much pricier these last few weeks. He’s not wrong, my husband. I touch the bone at the top of his shoulder, then slide my fingers halfway to his neck. It’s a beautiful manbone, one that exudes power. It’s got a name, that bone. I stayed in school long enough to know what I don’t know.

My husband flexes his muscles at the touch of my hand. It’s what men do: You touch their shoulder bone, they show you strength. There’s plenty of ways to manipulate the man you love, and most of them you learn by watching. Overall you could say watching is the sort of thing I’ve done too much of in my life. I started early, too. First time I saw a man’s chest harden at judgment I don’t think I was twelve, even. And then I saw that same man’s chest buckle at the soft sound of a compliment, and I learned that all can happen in the span of a moment if the woman’s a good twister of words, a good singer of their music. Jacks, I say, baby. I sigh, a whisper of air. I’m not brave like you.

My husband feels guilty when I say these words; I can see the color of blame in his eyes. He wishes his schedule allowed him to walk me to the subway whenever I left our apartment. And in his wishing he imagines me a more powerful woman than I am. Your spine is made of little eyes and ears, baby, he tells me. Whenever I open the fridge for a beer, you yell from the bedroom. “Easy on the fizz, Jacks.” A Pusher try to make a move on you on the platform? Next thing, we’re at his funeral, offering condolences to his mama.

I say this to Betty Boop the next day on the phone, I say maybe Jack’s right, maybe I’ve been more scared than I need to be. I say, It’s true that I got better instincts than most. Betty says it ain’t right.

Betty and I have been friends since the first nursing home we both worked at, and the thing about spending your days with old people is you get in the habit of saying exactly what you think. As your man he should make sure you buddy up when he’s not around, she says. Buddying up is what’s considered safe now, ever since Pushers started popping up, shoving or kicking people in front of trains. They believe they’re saving the planet, according to most rumors, but I don’t see how that can be right. I buddy up with you, I tell Betty Boop. When you do it’s no thanks to him, she says. She exhales with agitation. Maybe he mean well, she says, but telling you a Pusher’s got nothing on you can get in your head, make you less alert. People die that way all the time, she says. About a hundred people a day, to be exact: across boroughs and stations, men, women, and children. Don’t worry about me, I say.

Betty Boop is what Jack calls Betty, and I guess it got in my head. Sometimes I almost slip and call her that to her face. She’d slap you if she heard, I say to Jack. What? he says. It’s a compliment.

The next day after our shift, Betty and I walk down the subway stairs and hit a storm of people. Betty looks at me. This ain’t right, she says. She wants us to U-turn. What, and walk? I say. I want to get home in time to cook dinner for Jack. He’s been having a hard time: work stress, subway stress. Last night he woke me up shaking. I dreamt you died, he said, I dreamt they pushed you. Oh, baby, I said. I rocked him like a child until we both fell back asleep. Fine, Betty says, fine. She shakes her head at me. She keeps looking around, keeps looking everywhere. I do the same to show her we got this.

I reach for Betty’s hand and clench air. I yell her name and the sound is swallowed in the echo. Squeals pierce the air as bones meet gravel.

The thing about a crowded platform, you’re not guaranteed to stay far enough from the tracks to be safe. A wave of bodies rises and falls; I reach for Betty’s hand and clench air. I yell her name and the sound is swallowed in the echo. Squeals pierce the air as bones meet gravel. Wheels roll over, then screech to a halt as they do, as they always do, as if in surprise. Trains will be out of commission now for a few hours, until the bodies are removed. I tell myself it’s fine. This has happened before — we’ve lost each other in the crowd. I imagine that I see Jack in the distance; my mind plays this trick on me sometimes when I need comfort. As I climb back up the stairs, my body knows something bad just happened. I call Betty again and again when I get home, text her a million question marks. My breath aligns itself to the Web page: inhale on every refresh, exhale on every new list of names that doesn’t include Betty’s. And then her name is there, staring at me, daring me to stare back. I look away. I turn my back on that screen and go curl up into myself in bed, where I stay for days.

Jack makes pots and pots of tea, leaves full trays on the nightstand even though the food goes to the trash every morning. I keep the blinds shut to keep the darkness in. Jack knows to let me grieve. But on the third or maybe fourth or maybe fifth day, he enters the room with intention. You gotta eat, he says. I want to ignore him and go back to sleep, but his shoulders are big and I know he has something important to say. I’m not hungry, I tell him. See, the thing is, baby, he says, a body gets weak without food, and we need you strong for Friday. In the dark of the room I can barely make out his face but I squint at him like we’re in the sun. What’s Friday? I ask. Your initiation, he says.

I’ve heard rumors about Pushers’ initiation ceremonies but that can’t be what Jack is talking about. I sit up and reach for the light switch, but Jack’s hand is faster. There’s nothing to see right now, he says. He leans over and puts his other hand over my heart. Listen to what you already know, he says. He’s standing over me in an awkward position that would be funny any other time. And maybe it’s the shock, or maybe I don’t believe Jack’s saying what I think he’s saying, but whatever the reason: What I do is tickle his armpit. Jack collapses on the bed in surprise. He looks at me. Is that a yes? he whispers. You’ll join the underground? I see terror in his eyes, or maybe the terror is inside me. Why do I feel like I don’t have a choice? I whisper back. I want Jack to say, Don’t be crazy, baby. What he says instead is, None of us have a choice; our home is on fire. I know he means the planet but I’ve never heard Jack worry about the state of the Earth; we don’t even recycle. And pushing people is going to . . . kill the fire? I ask. They have data, baby, he says, real data, not the bullshit in the news. We’re on the express line to nonviability, and mass death is the only means of disruption. If anyone asked me yesterday, I would have bet my life on Jack not knowing what any of these words meant. Guess if I did that, I’d be dead now.

It is almost dawn when I wake up. Jack is sitting on his side of the bed staring at me. I don’t remember how we fell asleep. I don’t remember anything at first, but then I do, and the memory hits like the kick of a foot to a soft part. Who are you? I ask. Don’t be crazy, Jack says. What happens to me if I say no? I ask. You won’t, Jack says. Were you there that day, I ask, when Betty . . . ? Jack closes his eyes. I want you to know something, he says. The feeling you get from pushing a body? You haven’t been alive until you’ve known that rush. The inside of my mouth is turning to cement. Jack offers his hand to me. Let me show you, he says. Let me take you to the tracks. ●

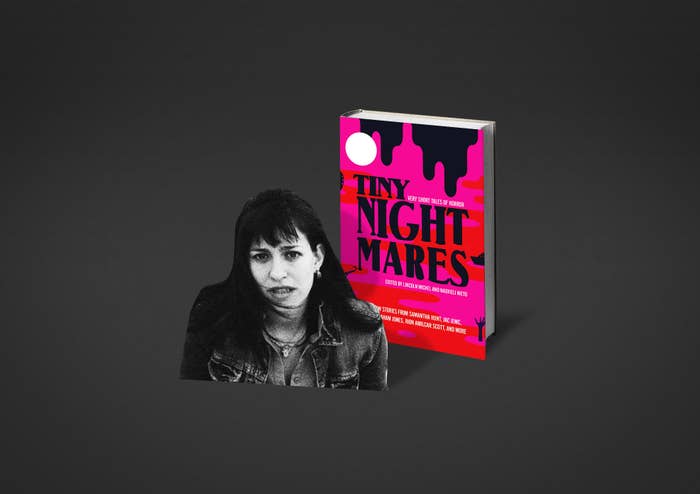

Shelly Oria is the author of New York 1, Tel Aviv 0; the co-author, with Alice Sola Kim, of the digital novella CLEAN; and the editor of Indelible in the Hippocampus: Writings from the Me Too Movement. Her fiction has appeared in The Paris Review and elsewhere, has been translated into other languages, and has won a number of awards. Oria lives in Brooklyn, New York, where she has a private practice as a life and creativity coach.