There’s a scene in The Shawshank Redemption — that 1994 feel-good prison break classic — when after more than six years of effort, our scrappy inmate-hero, Andy (Tim Robbins), finally receives funding to begin building a prison library. Soon, bookcases are being assembled, boxes of dusty used novels are being unpacked, and Andy is rattling off where to file the works of authors like Robert Louis Stevenson and Alexandre Dumas (whose name is initially pronounced “dumbass” by the inmate doing the filing).

“By the spring, Andy had transformed a storage room smelling of rat turds and turpentine into the best prison library in New England,” a dulcet voiceover from Morgan Freeman tells us, as the camera pans to a bustling room filled with inmates plucking books from well-stocked shelves and crowded around hand-carved wooden reading tables.

Reality, though, isn’t so charmingly bespoke. Today, prison libraries are hit-or-miss, more often falling on the “miss” side: frequently barebones, stacked with outdated textbooks, or littered with battered romance novels. Some prisons are even attempting to do away with libraries entirely, instead placing the burden on inmates to pay for e-books. In Pennsylvania, inmates have to pay for a $147 tablet in order to read books.

“The quality of the libraries is very uneven. People don’t have access to the books they really want to read, particularly if they’re on a specific subject. Some prisons try to do interlibrary loan, but it’s a very delayed service and, again, limited,” explains Katy Ryan, a professor at West Virginia University and cofounder of the Appalachian Prison Book Project.

Ryan shows me a recent letter from an inmate in Tennessee describing the library at his correctional facility. “Our library here isn’t very big, and besides, getting to it takes an act of Congress,” he says in nimble, attentive handwriting. “I am an indigent inmate and have no T.V., radio, etc., so books are my life. A fellow inmate said you guys could help me get some new reading material.”

Fortunately, he’s written to the right place.

The Appalachian Prison Book Project (APBP) is a nonprofit organization based in Morgantown, West Virginia, that sends free books to incarcerated people across six states in Appalachia: Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia. Founded in 2004 by Ryan and fellow professor (and recently elected Morgantown deputy mayor) Mark Brazaitis, APBP was born out of a class Ryan taught on the literature of incarceration.

“While reading works from formerly incarcerated or currently incarcerated people, we learned how important books were to them,” Ryan explains. “I mentioned to the students that I didn’t know if a prison book project existed in West Virginia. It turns out, there wasn’t one in the entire region. So, we carved out those six states, and committed ourselves to sending books to people who wanted them.”

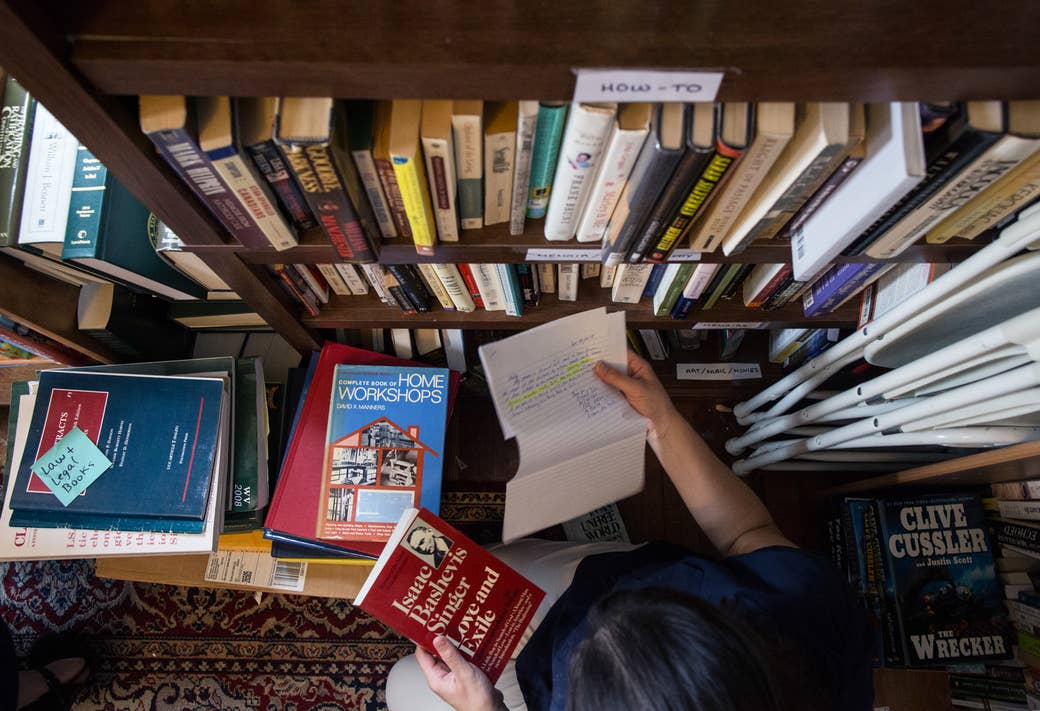

Ryan’s all-volunteer organization started its work from a church basement, then operated briefly out of a graduate student’s apartment, then finally found a home inside the Aull Center, a historic building in downtown Morgantown where the small, donated office space — which Ryan says has “an ineffable spirit” and volunteers frequently reference in magical terms — is stacked high with incoming letters and outgoing books. At any given time, there are up to a dozen volunteers, all of whom have been trained in the APBP system, matching inmate request letters with books on hand — or putting out feelers to rustle up a book on the topic (or by the author, or in the language) requested. The majority of books donated are from the local Morgantown community, but APBP also regularly receives packages filled with novels, how-to guides, and beyond from across the country. Soft-covered books are preferred to hardbacks (which are more difficult to get into prisons), and when it comes to anything small-press or handmade — comic books, zines — staples are a no-go. The entire process is powerful in its simplicity: Once a letter is paired up with a proper book, volunteers simply record it in a handwritten log as a “match,” then deliver it to the post office.

The incarcerated grapevine — and the need for books — is strong.

“The [APBP] office is open six days a week, so people can come in and respond [to letters] at their own convenience. It’s woven into people’s lives,” Ryan muses. “There really is something very modest about what we’re doing. We’re just trying to get books to people who want to read, and it can be difficult to get books into prisons other ways.”

Within prisons, information about APBP spreads primarily via word of mouth or letters between incarcerated individuals in different locations. Ryan says that even before the program was officially up and running, they received dozens of request letters from inmates all over the United States based solely on communication networks within facilities. The incarcerated grapevine — and the need for books — is strong.

The driving force behind APBP, undoubtedly, is Ryan, who powers APBP on the enthusiasm of her community, the help of students from West Virginia University, and modest nonprofit grants. Ryan is the daughter of a social worker, and working with youth in the juvenile system in the early ’90s set her up for a lifelong commitment to the social justice movement.

“I’ve always had this romantic belief that every person has value, but it’s easy to say that then forget about incarcerated people,” says Lydia Mae Welker, a volunteer social media coordinator for APBP. “Once I started working with APBP and reading the letters [from inmates], my worldview shifted, because I hadn’t included these people before. That’s something that was a big change for me.”

Ryan, who is remarkably modest when talking about her own role within APBP, is quick to point out the massive impact the program — and everyone involved in it — has had on incarcerated communities throughout Appalachia over the past 14 years.

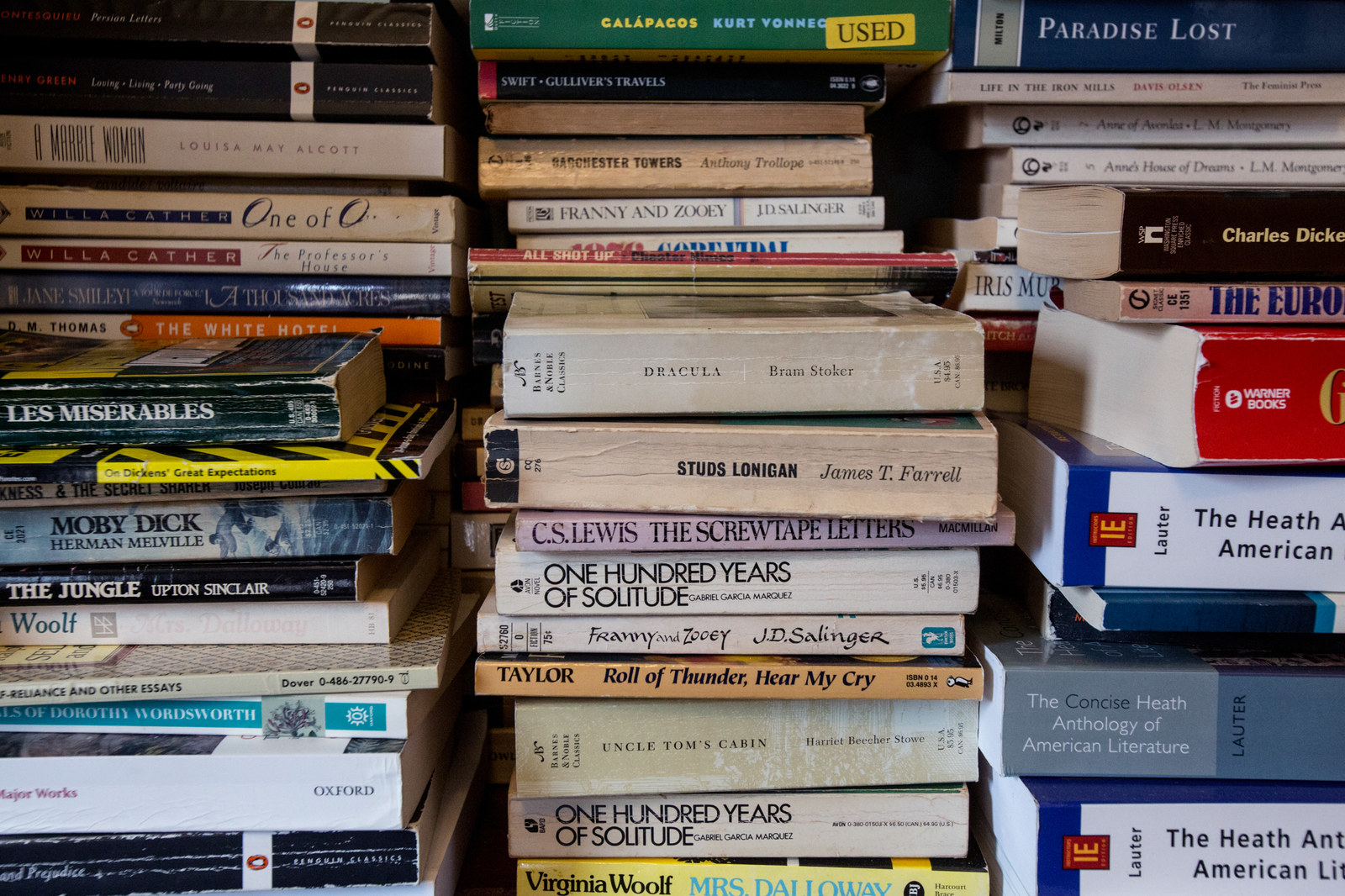

APBP is one of roughly 30 prison book projects across the United States, most of which focus on a specific state or geographic area. (One notable outlier is the LGBT Books to Prisoners program, which sends works to inmates looking for LGBT titles in every state.) APBP receives roughly 100 letters a week from inmates, and has distributed approximately 25,000 books total to date. Almanacs and encyclopedias are frequently requested, and an Amazon wish list outlines their latest needs: books about drawing, Westerns, sci-fi novels, books of Wiccan spells, how-to manuals for surviving off the grid, Spanish-English guides, and Chicken Soup for the Recovering Soul. The most requested book, by far, is a dictionary.

“Every third or fourth letter we get is a repeat, because they say thank you for the last book, and then tell us what they want to read next,” Ryan says. “People in the letters often speak of books like company — it has to do with imagination and creativity. That word ‘lifeline’ comes up a lot.”

Sometimes, APBP receives a letter asking for a book that’s so specific or unusual that it leaves volunteers scratching their heads. That’s where Dennis Allen — and the power of social media — comes in.

A retired professor from WVU, Allen is in charge of APBP’s “special requests” program: an effort to find asked-for books on obscure or hyperspecific topics (like, say, how to open a food truck) that don’t show up regularly in APBP’s donation rotation.

“This isn’t a bad guy, and if the books help him pass the time, then great!”

“Special requests are for those people in search of one very, very specific thing,” Allen says. “So, if an inmate is looking for a book on how to build a ‘battle-bot’ — which is a request we’ve gotten — we could go and get a novel and send it to him, but he’s not going to be happy with that. Instead, I get on Facebook and say, ‘This inmate wants a battle-bot book! Can anyone help us out?’ When I put up [the battle-bot] call, I didn’t know if that book even existed, but turns out, it does! Someone found a used copy and brought it in, and we sent it off to him.”

Allen estimates that 90% of special requests are fulfilled, usually in only two to three days, including everything from German language books to books on plumbing to a historical work about a singular 1974 coal mining dispute. APBP recently posted a general call for comic books — manga, Garfield, and everything in between — to which community members on Facebook (roughly 1,400 folks) enthusiastically responded.

“These special-request books feel like the good part of Christmas,” Allen laughs. “You can send them the book they requested and say, ‘Merry Christmas! This is exactly what you asked Santa for.’”

For members of the Morgantown community who might be hesitant about becoming involved, Allen is convinced that — like in most situations — understanding is the enemy of fear. Based in a thriving college town of roughly 30,000 residents, APBP is able to recruit the bulk of their new volunteers through both university connections and the passionate evangelizing of current APBP workers.

“If people are concerned [about getting involved], I’d tell them to come in and read some of the letters. They’re mostly in there for drug convictions, and are often quite touching. I read one letter from an older guy who said, ‘My wife died, and I started getting into trouble.’ And I’m thinking, This isn’t a bad guy, and if the books help him pass the time, then great! They’ll say things like, ‘You’re locked in your cell 23 hours a day; send me the longest thing you have!’ That’s because you get through short things in only a couple of days. They are very grateful.”

While the written contents of the letters themselves are deeply moving, there’s a more surprising element that often strikes a chord with volunteers: the complexity and beauty of the art that often appears both within the letters themselves and on the envelopes. One envelope sent from Virginia has a school of dolphins etched in pencil floating gracefully across the front, bubbles trickling upward to the paper’s edge. A stylized, folksy ink drawing out of West Virginia places a radiant sun rising out of the corner of the envelope with the words, “Country roads, take me home!” written in a curlicue font.

“Part of what happens is that the letters themselves are so personal and idiosyncratic that they do a lot of the work undoing the [prison] stigma,” Ryan says. “Any stereotype you might have will be eroded by reading the letters, particularly when drawing a beautiful rose on the envelope doesn’t really fit with what you might think about a person in prison.”

Humanity is a frequent point of discussion when it comes to the prison system: the general lack of it, and the difficulty in supporting programs to bring it back on the “inside.” Almost a decade after APBP launched, Ryan started the nonprofit’s first in-person book club within a women’s federal correctional facility in West Virginia as a means of taking the educational component of APBP to the next level — to strengthen the human connection. The reading list for the group ranged from Jhumpa Lahiri’s Unaccustomed Earth to Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, with a large percentage of the books focusing on issues of social justice and prison reform, and first-person works from those who had been in positions similar to the book club members. Kirsten Wilkinson of Washington, DC, points to Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse as a work that helped to push her outside her comfort zone, and Americanah for sparking an interest in author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. (She went on to read Adichie’s We Should All Be Feminists after her release.)

“If you don’t know what it’s like inside, it’s hard to explain, but the inner sanctum of the book club was everything for me.”

“When I saw the flyer [in my unit] for the book club, I knew I had to be a part of it,” explains Jean Michel Cross, who was a part of the women’s book club until her release last year. “It was a limited group, and we had to ask our supervisors to participate. I was a literature major in undergrad, so I just scratched and clawed to make sure I was selected to be a part of the program.”

Others, though, were more skeptical of the book club at first. “I just wanted something to read and to occupy my Sunday, and that’s how it was going to be,” says Wilkinson, who was also a member of the book club until her release in January 2017. “But before you knew it, I couldn’t shut up about my opinion on the books during our discussions.”

The group, which met on alternating Sundays, was composed of roughly 15 members who were serving sentences for sweepingly different offenses — from embezzlement to second-degree murder.

“I was so grateful to find the book club, I just wanted to cry,” Cross says. “If you don’t know what it’s like inside, it’s hard to explain, but the inner sanctum of the book club was everything for me. Everyone was very respectful and well-behaved, and they appreciated and respected what was going on around them. Plus, Katy treated us with dignity.”

But setting up — and maintaining — educational programming inside prisons isn’t so simple. “The system keeps cutting back on programs, but they don’t realize what an impact something like [the book club] makes on a life,” Wilkinson says. “It helps more people than they think, and not all of them talk about it. If you lose hope in people and don’t give them a chance with these programs, they’re just going to come right back through like a revolving door.”

For Cross, one of the most compelling parts of the book club discussions was hearing from individuals serving life sentences.

“There were lifers in our group, and when you’re a lifer, your perspective on everything changes. They had so much to offer. They were not pity-partying; they weren’t blaming. They simply wanted to think, and wanted to process, and wanted to express themselves.”

Soon, book club members weren’t just taking notes on their readings and scribbling discussion points in their book margins — they were creating stories of their own.

“They’d have these letters that they’d written to their children about the book they’d been reading,” Ryan says. “We started alternating our sessions between a book and sharing writing.”

“A lot of people didn’t want to do [the writing] part at first, but we all broke out of our comfort zone and expressed ourselves,” Wilkinson adds. “I remember one girl who wrote about being abused, but if you had met her, you wouldn’t have known it — she had this kind of upbeat energy. You can’t help but cry thinking about how that could happen. But you saw that a lot in the group: It was a nice, calm place to talk about your feelings and be you and tell someone, ‘I’m really hurting inside.’”

The body of writing produced by the women’s book club grew so vast that Ryan, along with her colleagues at WVU, gathered over two dozen of the pieces and crafted them into a self-published book entitled Women of Wisdom (WoW, for short). Named by the book club members, the collection of short stories, narratives, poetry, and illustrations is an emotionally raw, deeply personal meditation on weaving together a complicated past with the challenges of incarceration and, in many cases, hopes for the future. (WoW contributor Melissa “MJazz” Hicks, for example, writes in the collection: “Prisons overpopulated, politicians break laws like me, / Judge sentences us to life, yet set his own colleagues free… / This epidemic of injustice sickens me, / What happened? What went wrong in the land of the free?”) In what is nothing short of a cathartic full circle, the occasionally reluctant readers had become authors themselves.

In what is nothing short of a cathartic full circle, the occasionally reluctant readers had become authors themselves.

For those who have never been impacted by incarceration, WoW is a document that should be required reading. Too often, there’s the tendency to draw a finite line between those on the outside and those on the inside in an attempt to morph those incarcerated into an “other.” This all-too-common practice plants the seed (or stokes the fire) of discrimination against those both currently and formerly incarcerated. The immense strength, earnestness, and, often, self-reflection found within the pages of WoW demolishes any notion of an “us” versus “them.” Rather, WoW speaks to how we’re all just in various phases and stages, trying to do our best to be at peace with ourselves.

For Alex Kessler — who helped to found APBP’s men’s prison book club — the importance of placing the writing of incarcerated individuals alongside the works of nonincarcerated artists has become something of a moral creative calling.

“There is another America running parallel to our own, and people’s walls need to come down about it,” he says. “It’s an issue of visibility. It’s easy to turn away from incarcerated people or publications that just focus on people writing about their time on the inside. It all needs to be presented together, because publications need to have representation from incarcerated voices.”

Kessler excitedly mentions the writings of a member of the men’s book club named Antoine, whom he grew to consider not only an exceptional talent, but a friend.

“Antoine is a very funny guy, and his humor was a big part of the book club,” Kessler laughs. “But when I started reading his work, I told him, ‘You need to be a writer.’ He has a knack with words and can phrase things in a way I’ve never heard. When you see a one-of-a-kind mind, you have to encourage it.”

Kessler eventually worked to have Antoine published in the WVU literary journal, Calliope, where for the first time, an incarcerated man’s vision sat prominently alongside those of creative writing majors and budding literary scholars. It was, undoubtedly, a moment that felt victorious.

“Getting Antoine published in Calliope was one of the few moments when I’ve been 100% sure that literature matters and is worth it,” Kessler, who is entering a PhD program this fall, explains. “When something like the book club — and everything that comes from it — works, it’s completely different than the feeling on a college campus. You’re giving access to a world that wasn’t there before.”

Ryan mentioned that one of the first books the women’s prison book club read was Kindred by trailblazing African American science fiction writer Octavia Butler. The story of a black woman in the 1970s who travels back in time to a plantation in antebellum Maryland, it is a tale about, among other things, how suffering and injustice that happens away from public scrutiny — whether in the past or sequestered behind barbed-wire fences — can all too easily be forgotten or ignored.

In Kindred, Butler describes slavery as “a long slow process of dulling,” and it’s not difficult to see prison in a similar light. Prisons have been machines of systemic racism and classism for centuries, so the fact that being treated like a human — much less a human with mental and emotional needs — is such a rarity in prison comes as little surprise.

“My biggest fear and concern [while inside] was not being allowed to go to book club. Schedules don’t always go according to plan, and there are lockdowns after lockdowns,” says Cross. “Book club was freedom of thought and freedom of expression, no games being played like there were in the units. It was a moment of exhaling and cognitive exercise: People really cared about what we thought and listened to what we said.”

Books are a balm: a means of traveling time and space from a concrete cell; a link to those in similar situations or from completely different worlds; a vehicle for planning a future — and a hope for something different — on the outside.

And while APBP would never say such a thing (Ryan notes that APBP has found little public resistance because “no one wants this level of incarceration”), it’s hard not to view APBP as an activist organization: one that’s doggedly committed to using the lone arrow in its quiver — books — to send messages over the tall fortress of metal and rock that keeps prisoners from receiving almost all other communications from the outside.

These books become messengers of persistence, messengers of peace, messengers of growth, to be sure. But perhaps most importantly, they become messengers of survival and, ultimately, liberation — at least until the end of the chapter. ●

Sarah Baird is an award-winning writer whose work has appeared in the Washington Post, GQ, the Guardian, the Atlantic, and more. She divides her time between New Orleans and Kentucky, where she was born and raised.

This article is part of a series of stories celebrating libraries and free access to information.