There are few things as thrilling as a 60% off sign, particularly when it's hanging above something you actually want to buy. But the tactics stores use to give you that heady “I just got a bargain!” rush are under siege.

Chains from Kohl’s to Nordstrom Rack have been fighting a massive wave of class-action lawsuits in the past few years questioning just how legitimate their discounts really are. Since 2012, consumers have filed at least 35 suits, mostly in California, saying they were duped into buying goods they wouldn’t have otherwise purchased based on phony discounts, BuzzFeed News has found. And they want their money back.

The suits claim there's a bait and switch going on: You walk into a store, see a jacket on sale for 40% off, and buy it based on what a great deal is it. But it turns out the jacket was never sold at that original price. In other cases, let's say you walk into an off-pricer or outlet mall and see a purse for 30% off its original price. Later, you find out it was never sold anywhere else. Is that fair?

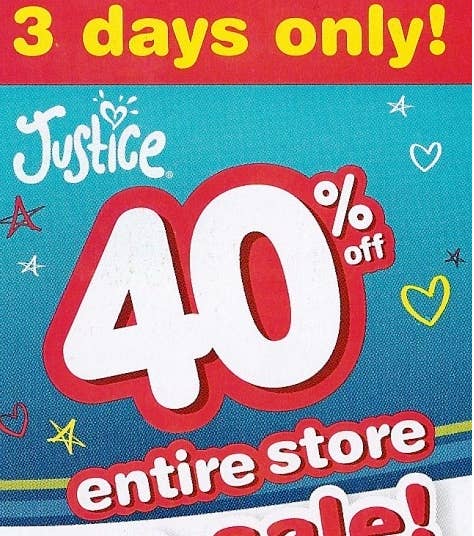

Last year showed some of these cases have teeth: J.C. Penney and tween chain Justice — the modern-day Limited Too — set aside about $50 million each to settle allegations that they were using 40% off prices as their regular prices. And Michael Kors paid $4.9 million to settle a lawsuit that alleged its made-for-outlet goods were misrepresented to consumers as discounted full-price merchandise. As part of that, it also agreed to change the labeling on outlet-only items. The retailers didn’t admit to any wrongdoing as part of the settlements.

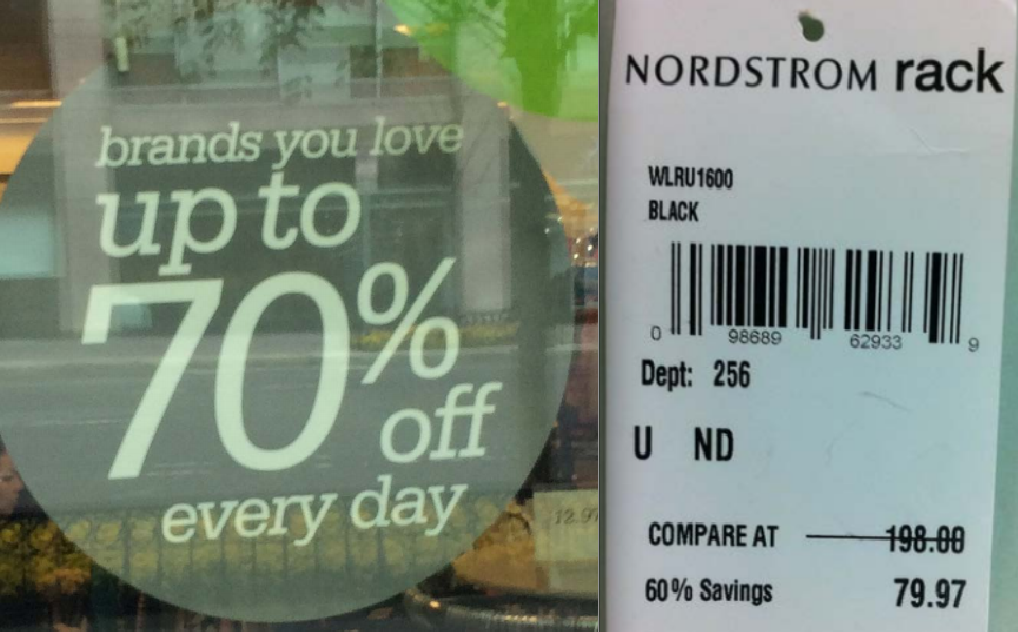

Together, the claims from consumers draw into focus America’s obsession with deals and the many ways retailers have fashioned their businesses around catering to that demand. Outside of rampant 40% off sales and coupons at the mall, recent years have seen the proliferation of outlet stores, where lower-quality clothes are often hawked at big purported discounts, as well as the rapid expansion of “off-price” chains like T.J. Maxx and Nordstrom Rack, which promise savings of up to 60% and 70% every day. Express is even bringing its outlet stores into some malls.

Such tactics, known as "high-low pricing" and "price anchoring," have become easy ways for retailers to attract value-conscious consumers, especially in a sluggish economy. But with everything on sale all the time, shoppers have started questioning where, precisely, that “percent off” is coming from.

“There are so many pricing models that are available right now that it’s truly difficult to identify what is ‘regular price.'"

“There are so many pricing models that are available right now that it’s truly difficult to identify what is ‘regular price,’” Priya Raghubir, the chair of the marketing department at New York University’s Stern School of Business, said in an interview.

Law firm Sedgwick LLP, which is handling many of these cases nationally, told BuzzFeed News that by its count, deceptive pricing lawsuits have been brought against 29 separate retailers in recent years.

While a number of the attempted class-action lawsuits have been quickly dismissed and the fairness of payouts hotly debated, retailers' defenses illustrate how convoluted the notion of a "regular price" has become.

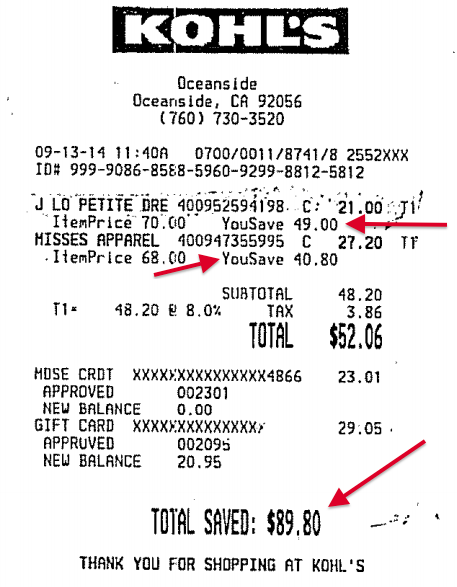

Kohl’s, facing two suits tied to discounts, said that when it shows a “regular” or “original” price, it's referring to the former or "future" price on any given item. And it might mean that item or it might mean a "comparable" one. And it could be at Kohl's, but could also be at another retailer. And after all that, sales may not have ever been made at the regular price, it notes.

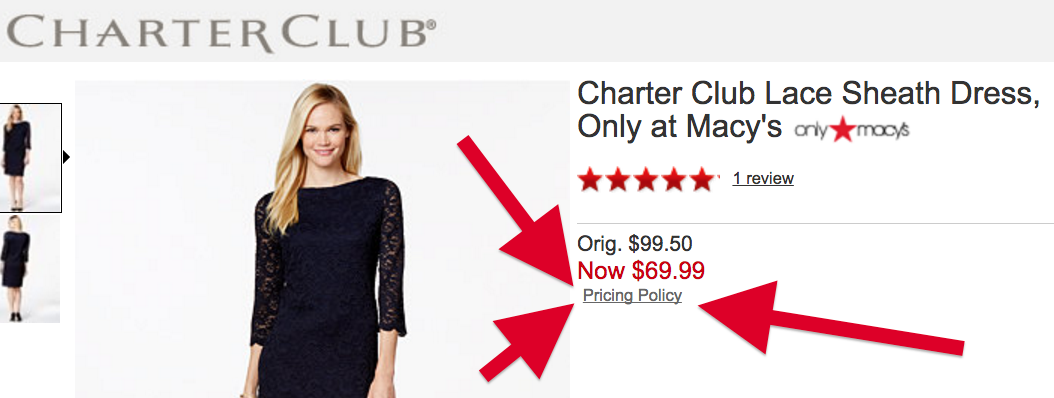

Macy's seems to be proceeding cautiously with a small "Pricing Policy" link on item pages, which opens a window that says: "'Regular' and 'Original' prices are offering prices that may not have resulted in actual sales, and some 'Original' prices may not have been in effect during the past 90 days."

Nordstrom, in another suit, defended the "compare at" prices on some of its tags at Nordstrom Rack, saying the label could mean one of four things. It could be a manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP), a price confirmed as the "pre-discount market retail price" by Nordstrom Rack's suppliers, the price that other retailers are charging, or the price of "like, non-identical goods in the relevant market," lawyers wrote.

When It All Began: J.C. Penney and the Outlet Letter

The lawsuits against retailers started proliferating around the time then–J.C. Penney CEO Ron Johnson tried and failed to kill off the chain's endless sales and coupons in 2012. In explaining his vision, the former Apple retail chief revealed that hardly anything at the store was sold at full price in 2011, a year in which the company ran 590 separate promotions. Even though its costs didn't change much in the previous decade, he explained during a January 2012 presentation, J.C. Penney kept raising its prices — allowing the company to offer customers bigger and bigger discounts.

While Johnson's plan to remake department store prices flopped, his efforts cast a new and uncomfortable spotlight on bargain shopping and the authenticity of any given deal — and some consumers didn't like what they learned.

Most of the lawsuits are in California, which has strict consumer protection laws, including one that says any "former" price advertised on an item has to have been its "prevailing market price" in the previous 90 days.

The suits got an extra kick starting in January 2014, when four members of Congress asked the Federal Trade Commission to investigate "potentially misleading marketing practices by outlet stores." Since then, a slew of more complex complaints over comparable prices — which are perfectly legal when used correctly — have been brought against retailers like Last Call by Neiman Marcus, TJX, Kate Spade, Burlington Coat Factory, and Kenneth Cole Productions.

“Contrary to what corporate America would like you to believe, consumers don’t like being screwed constantly,” said Hassan Zavareei, a lawyer who worked on the Michael Kors case and is involved in deceptive pricing lawsuits against Nordstrom and Jos. A. Bank. “These corporations, a lot of them, don’t mind lying to consumers to get them to buy stuff — that’s what it’s all about."

It's also about money: The lawyers who brought the J.C. Penney case have asked for at least $13.5 million, or 27% of the company's $50 million settlement fund. Those in the Justice case, owned by Tween Brands, are asking for $15 million.

From $14.99 Blouses to a $50 Million Settlement

In the J.C. Penney case, filed in 2012, a consumer named Cynthia Spann allegedly believed she was saving 40% to 50% on a bunch of $14.99 and $17.99 blouses made for J.C. Penney with an "original" price of $30. Spann claimed she wouldn't have bought the blouses if she didn't believe she was getting a deal, and argued $30 wasn't their "prevailing market price" in the 90 days before her purchase. Her subsequent complaints cited comments made by Johnson, who was deposed as part of the case.

Last year, the judge's opinions in that case made a strong argument for certifying classes of consumers in such lawsuits, and, surprisingly, for offering restitution to consumers who paid more than they otherwise would have based on misleading marketing tactics. That's terrifying for retailers, who have argued that at the very least, consumers are still walking away with something valued at whatever they paid for it.

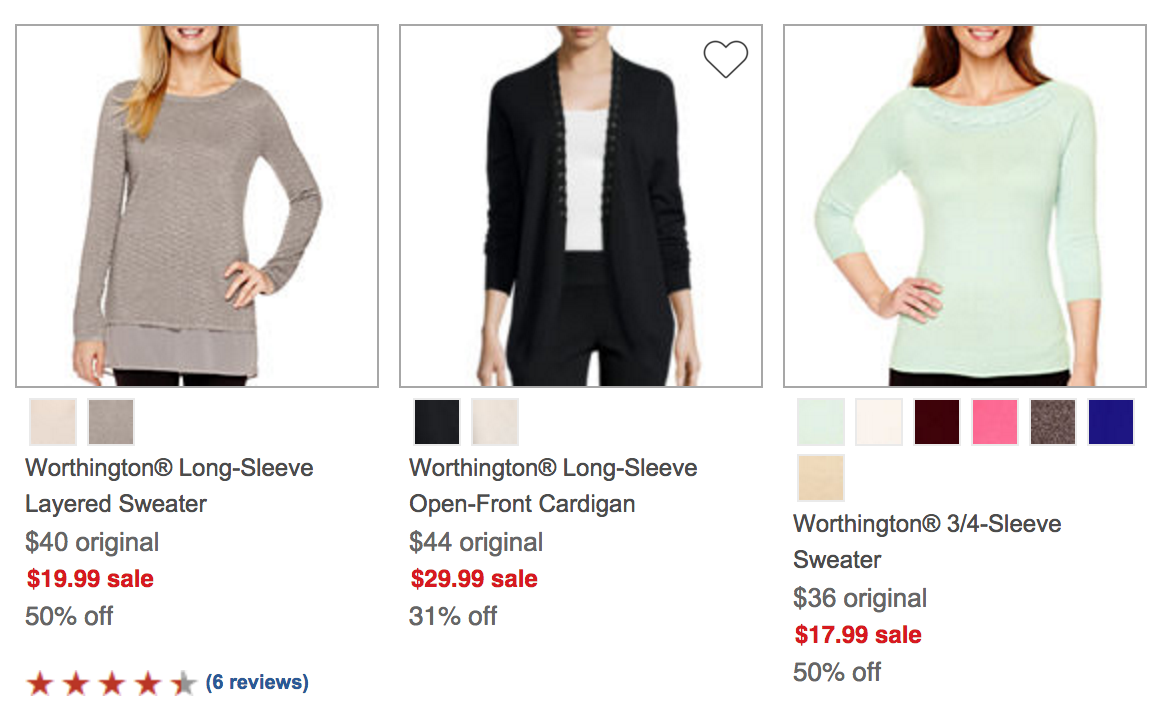

"Let's say I see a sweater that I really like and it says it’s $40 and it has a ‘compare at’ price — or ‘former’ price or ‘previously listed at,’ or whatever language you want to pick — saying it was $75,” said Stephanie Sheridan, a partner at Sedgwick and the head of its retail practice group. “At the end of the day, the consumer is making a voluntary decision to part with $40 of their money for the purpose of buying that sweater. There is an argument, too, that to you, you’ve decided that sweater is worth that amount.”

J.C. Penney chose to settle the case to avoid further risk, and, pending court approval, will likely make payouts of cash or store credit to most California consumers who bought exclusive branded goods from J.C. Penney at discounts of at least 30% in the past five years. In the Tween Brands case, compensation includes $20 cash payouts and $30 Justice vouchers.

Kohl's Defense: Some of Our Shoppers Don't Even Believe Our "Regular" Prices

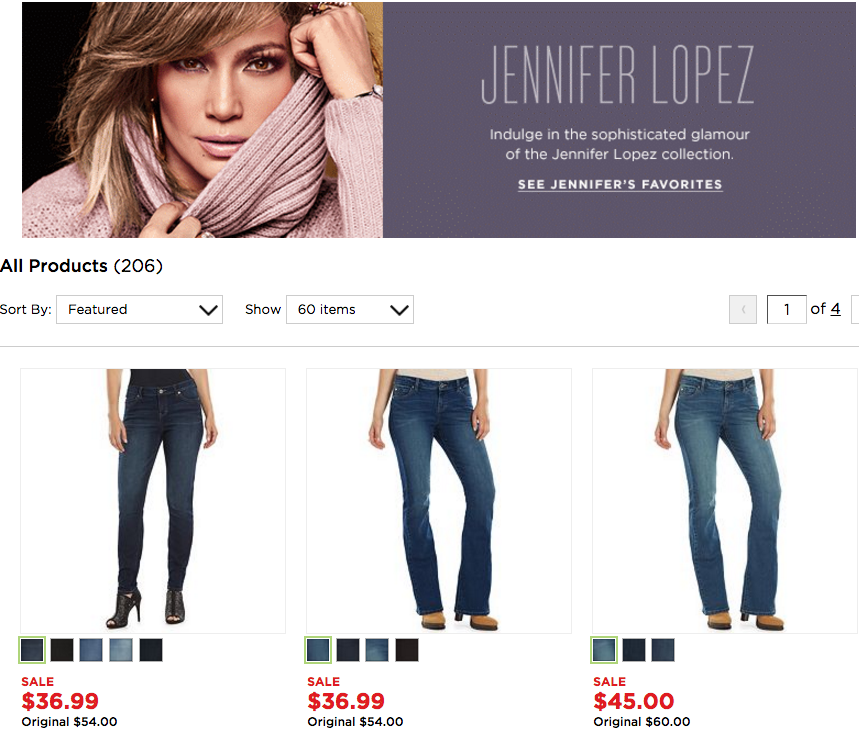

Kohl’s, with $19 billion in annual sales, has been accused of running perpetual sales, with a particular eye to the private and exclusive brands that make up half of its sales. Legally, it’s easier to make a case for deceptive pricing on brands sold by a single retailer, said Matthew Zevin, a lawyer who is representing consumers in one case against Kohl’s and who worked on the J.C. Penney case. In the Kohl’s case, such labels include Jennifer Lopez, Food Network, Apt. 9, and Sonoma Life + Style.

In one of the cases, which was recently dismissed, Kohl's retained a professor of marketing at Loyola Marymount University to research how Kohl's shoppers view prices.

David Stewart, the professor, conducted focus groups of Kohl's shoppers to "confirm that there is no uniform response to comparative price advertising," lawyers for Kohl's wrote in November. "Some Kohl’s shoppers pay little to no attention to 'regular' or 'original' prices in making their buying decisions; others do not necessarily believe the price comparisons."

The lawyers went on to cite research presented by the shoppers' side, saying it supported Kohl's position because "it shows that consumers often do not believe the 'regular' price and therefore would not be deceived by a false 'regular' price."

Kohl's lawyers also disclosed that each "regular," "original," and "sale" price is set by one of more than 200 people in Kohl's buying office, "each of whom applies his or her individual discretion, expertise and experience to the task."

"I believe in buyer beware, but I also believe in tell the truth.”

“What we’re saying is if the products come on the shelf with a sale price — how is that a sale if it was never offered at the regular price?” Zevin said. "I believe in 'buyer beware,' but I also believe in 'tell the truth.'”

Kohl's didn't respond to a request for comment from BuzzFeed News.

The Scrutiny on Nordstrom Rack

The lawsuit involving Nordstrom Rack reflects some confusion around what consumers are buying at the off-price version of Nordstrom. It's notable for a few reasons. First, Rack has said that less than 20% of its merchandise comes from regular Nordstrom stores. Second, Rack stores also now way outnumber full-price Nordstrom locations. And third, Rack's success has spawned a host of competitors including Macy's Backstage and Find @ Lord & Taylor.

A California shopper named Kevin Branca claims he bought two pairs of pants and a pair of cargo shorts from a Nordstrom Rack, believing he was getting full-line merchandise because the tags included "compare at" prices, which aren't included on all of Rack's goods. As part of his argument, he cited an online survey conducted for the case by a Towson University professor, which showed most consumers who saw the "compare at" tag in question believed the item once sold at that price in a Nordstrom store.

One point of tension in the case is Nordstrom's tagline on its website, which promises "the brands you love for 30-70% off original prices—each and every day."

Branca contended this mention of "original prices" suggested Rack goods were once offered for sale at Nordstrom stores — a claim lawyers for Nordstrom called unreasonable. The line makes "no reference to main line stores" and "no direct or even indirect statement that all Nordstrom Rack products were first offered at main line stores," they wrote.

"We are strongly committed to pricing integrity at Nordstrom Rack," a spokesperson for the company told BuzzFeed News. "Our practice is to put customers first and ensure that our customers are always satisfied with their cost savings."

So what does the "compare at" tag mean? Nordstrom said it shows the item was "previously offered for sale at that price either by another retailer (in-store or online), in a Nordstrom store or on a Nordstrom website," or it has "the same manufacturer and has the same quality as the item that was offered for sale at its 'compare at' price."

"If our buyer can’t verify that the item was offered for sale at the 'compare at' price, we simply don’t list a 'compare at' price on the tag," the spokesperson said.

Are These Lawsuits Legitimate?

That's for the judges to decide.

Plenty of the lawsuits have been dismissed or abandoned after judges decide against big economic damages, even if they agree that pricing is deceptive. Some consumers are lead plaintiffs in several of the cases. In one brought against Kate Spade over outlet pricing, shoppers argued they were "personally victimized" by the labeling.

"What some of the plaintiffs' lawyers' theories are as to what retailers should be expected to do to put a ‘compare at’ price on an item is so ridiculously impossible, it would never happen," said Sheridan, the lawyer at Sedgwick.

She continued: “Let’s say, for example, that a retailer has a dress that it’s selling for $80 and it knows that other stores or other places have sold this dress, or are selling this dress for double, for $160. So it puts that ‘compare at’ price on the tag. Some of the plaintiffs’ lawyers say before the retailer can put $160 on that tag, that retailer should be required to obtain and assess all of the sales records of all of their competitors to be able to establish that a substantial number of sales of that dress have taken place at the higher figure. It would be price fixing and no competitor is going to share that information.”

Still, others say there's a value in taking a closer look at sale prices and compare-at pricing.

“I don’t think that the lawsuits are frivolous at all,” Raghubir of NYU said. “I believe they really put companies on watch. To say, ‘When you are advertising a regular sale price, we are watching. So be careful before you try, for lack of a better word, to trick us.’”

What You Can Do as a Consumer

Some retailers are starting to add information to their websites on what prices mean or changing the way they label at full-price stores or outlets. Michael Kors used to mark some made-for-outlet goods with both "MSRP" and "Our Price." As part of its settlement last year, it said it would replace the "MSRP" with "value" and provide an in-store explanation of what that means. Or it will remove the reference point on those products altogether.

T.J. Maxx stresses online that its "compare at" prices don't necessarily refer to goods for sale elsewhere at any given moment. "We encourage you to do your own comparison shopping as another way to see what great value we offer," its website says. "We stand for bringing you and your family exceptional value every day – it’s the foundation of our business."

Research what you're buying at full price or outlet stores, and ask associates. Take the amount of a discount and "compare at" prices with a grain of salt, unless you're absolutely positive about a product's typical cost. Pay $40 if you believe a sweater is actually worth $40.