The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

When she doesn't take two small tablets of hydroxychloroquine every day, the pain and fatigue of Sharon Greenstein's autoimmune disease become too much to do even the basic things of daily life.

"I can't function," she told BuzzFeed News. "I can't work. I can't do daily activities. I feel pretty sick."

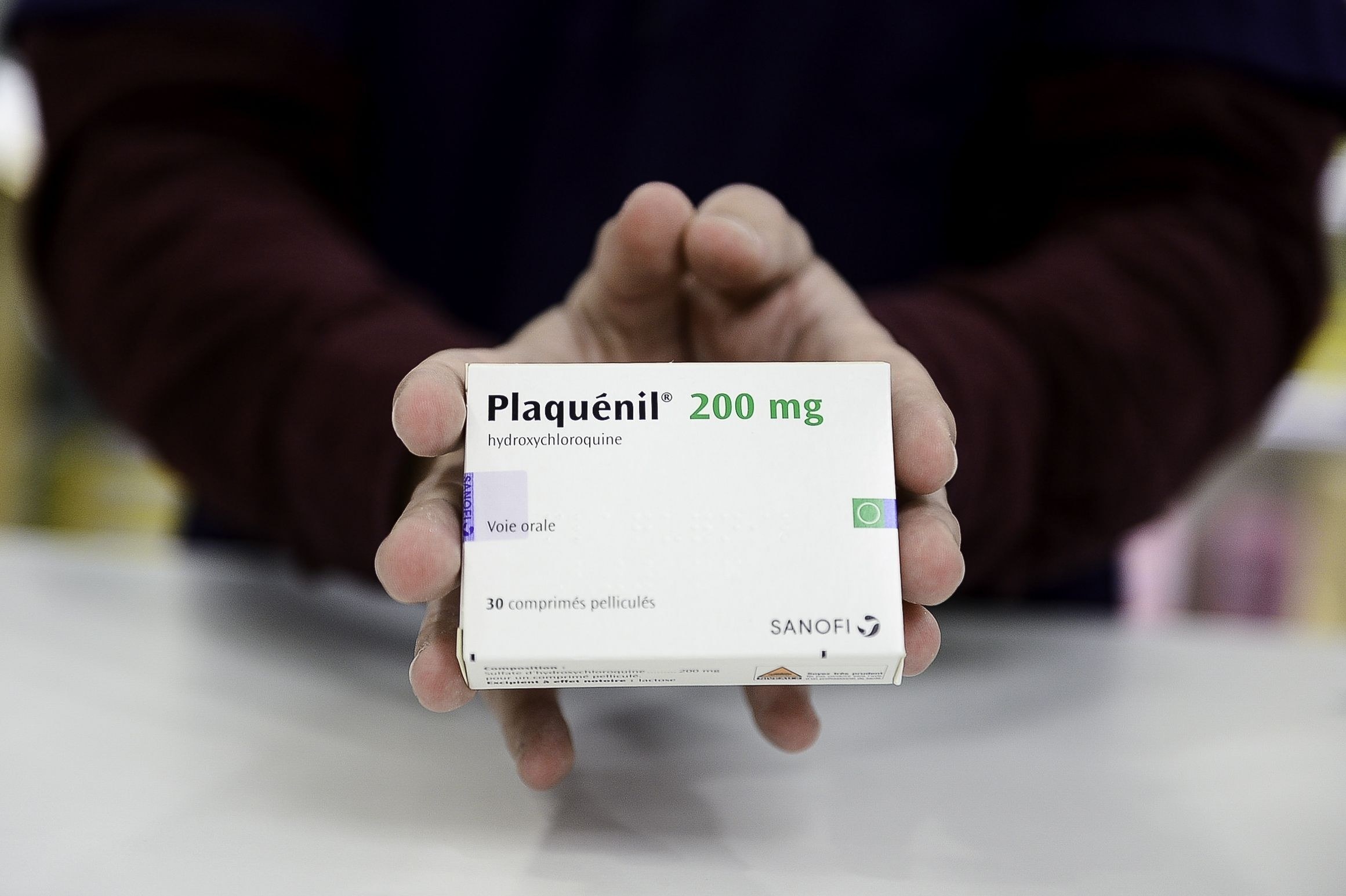

About 25 years ago, Greenstein was diagnosed with Sjögren's syndrome, a disease where the immune system attacks its own body. Since then, she's been prescribed hydroxychloroquine, a drug that's also been used to treat malaria, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis.

But after President Donald Trump announced last week that the drug could be a "game-changer" as a treatment for COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, a surge of demand hit pharmacies and manufacturers. Reports of people purchasing the drug and other products containing chloroquine to self-medicate began to surface, including a Phoenix man who died after he took a version used for fish tanks. (The use of chloroquine to treat COVID-19 continues to be studied, and doctors are recommending no one use it in any form to self-medicate.)

When Greenstein, who lives in California's Bay Area, went to her local pharmacy Friday to renew her prescription, she was told she wouldn't be able to get her refill until Monday. When she called Monday, she was told they wouldn't be able to fill her prescription at all.

"I was told that not only was there none available anywhere, but they didn't know when they were going to get any more," she said.

On Monday, the FDA told BuzzFeed News it was working with manufacturers to look at their supplies of the drug and the demand from patients who rely on it. It's still unclear when more of the drug will become available for patients like Greenstein.

After speaking with her pharmacy on Monday, she said the only option she had was to purchase a bottle of Plaquenil, the brand-name version of her prescription, which was priced at about $2,000 and not covered by her insurance. With the help of a relative, Greenstein found a manufacturer's coupon that brought the price down to $664.

She paid the price — 44 times her typical copay of $15 — and expects the bottle will last her about a month.

"I could do that one time, but there will be people who will be bankrupted by this," she said. "They can't do it at all."

If she were to run out of her medication under normal circumstances, Greenstein said her quality of life would be severely affected, but she wouldn't worry for her health. But now, as someone with an autoimmune disease, she's also dealing with the fear that comes from being at higher risk for serious complications if she contracts COVID-19.

For the past week, she's had a cough and fatigue. At first, she chalked it up as symptoms of Sjögren's syndrome. When she got a fever Saturday, she contacted her doctor, who said she qualified to get tested for the coronavirus.

On Monday, she drove through a testing site and is waiting for results.

In the meantime, she's isolated herself in her home with her husband and two adult children. Her bedroom has become a makeshift quarantine while they wait for answers.

She's talked to her doctor about not being able to get her usual prescription, and her doctor told her other patients are having similar problems.

The drug has faced such an increase in demand that pharmacies in Mexico have reported Americans coming across the border for boxes of it, with some who "arrive with a slightly bossy attitude," the Dallas Morning News reported.

In the meantime, Greenstein said her doctor has suggested she could take one daily tablet, instead of the usual two, to stretch her supply.

She said she's tried that before, and her symptoms returned. For now, she hopes the supply will be replenished by the time she runs low in several weeks, but she doesn't know what she'll do after that.

Paying more than $600 a month, she said, is not an option.