“Cock up yuh bumpa, siddung pon it!” I knew the words, but they were coming from an unfamiliar voice. Drake’s quick interpolation of Popcaan’s 2014 hit “Love Yuh Bad” on Views’ “Too Good” felt stilted, an awkward attempt to reconcile the fact that Poppy was missing from the album’s cut of “Controlla.”

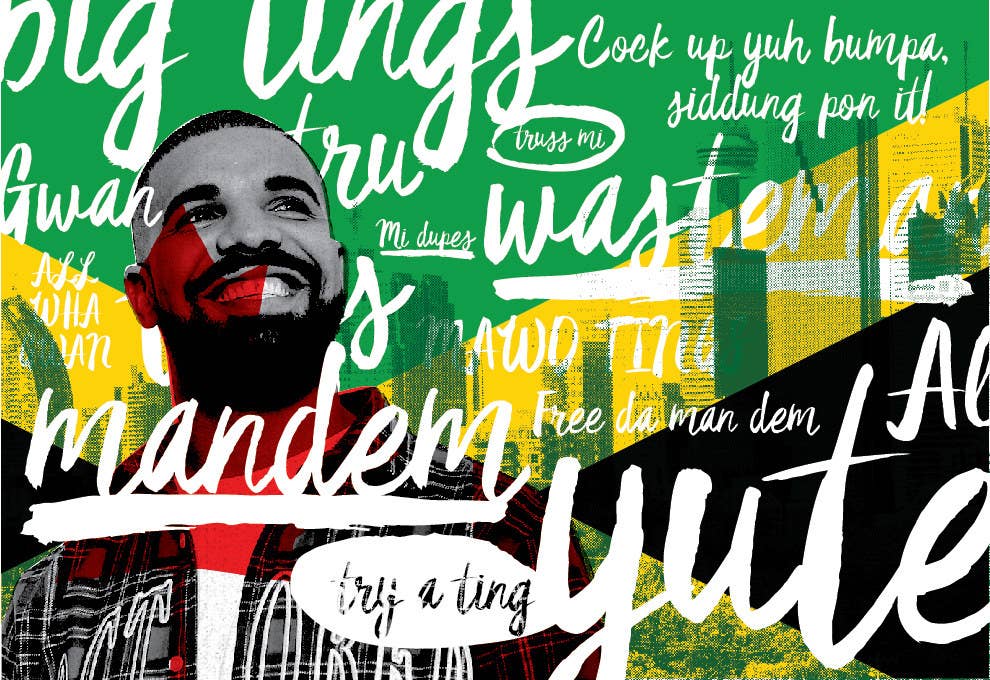

For many American listeners, Drake’s claim to Afro-Caribbean music and culture seems contrived and unexpected — another example of his tendency to “ride” a particular wave and then move on to something else. It begged the question: What could a half-black, half-Jewish Canadian know about Jamaica? “There are all these different sounds so far on Views,” some wondered, “but what does Toronto actually sound like?”

Connecting the dots between the frigid Canadian city and the sounds of the West Indies can be tricky for those who don’t understand Toronto’s cultural makeup. Just before the release of Drake’s 2015 mixtape If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late, the 14-minute film “Jungle” premiered on the official OVO website, following Drake as he waxed poetic about loyalty, loneliness, and the city he calls home. Many of his listeners were perplexed by his “new” accent: Flat, unfamiliar, and Caribbean-tinged, it would sometimes ramp up into full patois at various points of expression.

It was an accent I recognized immediately as distinctly us, though I knew it would be read as an odd hybrid of patois and “regular” English — which isn’t necessarily that far from the truth. As the Toronto-born child of a Jamaican mother and Trinidadian father, I grew up with Caribbean culture as a central part of my everyday life. To understand Drake’s proximity to reggae, and the islands in general, it’s important to understand what growing up in Toronto is like.

To understand Drake’s proximity to reggae, and the islands in general, it’s important to understand what growing up in Toronto is like.

Living in and around some of the city’s more highly concentrated pockets of West Indian immigrants, it was always clear to me that Afro-Caribbean culture was integral to the city’s makeup. In the 1960s and '70s, when revised immigration laws made it easier for people of color to come to Canada, large numbers of West Indians made their way over and settled primarily in Toronto and its surrounding areas. My own grandmother, mother, and aunts all came for this exact reason, gravitating toward the growing communities that were already present when they arrived.

Over the last few years, Drake has increasingly incorporated Jamaica and dancehall culture into his music and persona. Before his collaborations with artists like Popcaan, his social media feeds were peppered with patois phrases, dancehall lyrics, and homages to artists like Buju Banton and Vybz Kartel. Videos like 2010’s “Find Your Love” put Drake in Kingston, Jamaica, with dancehall artist Mavado as his archnemesis, while last year’s “Hotline Bling” found him bussing popular dancehall moves with the help of choreographer Tanisha Scott.

The release of Views opened up conversations about appropriation, and some pondered when Drake decided to start pulling from the islands as a reference point. For those of us who grew up in the city, it made perfect sense for him to gravitate to a sound that has been shaping it for decades. From Michie Mee’s and L.A. Luv's “Jamaican Funk Canadian Style” to Kardinal Offishall’s “Ol' Time Killin'” or “Bakardi Slang,” there are countless examples of Toronto-born artists putting reggae and dancehall sounds in the forefront of their creative sensibilities. But, unlike Drake, these artists were almost always of Caribbean descent themselves.

In his Beats 1 interview with Zane Lowe following the release of Views, Drake casually dropped plenty of patois — more than usual, perhaps. Admittedly, I cringed a little in the same way I did when he took the stage in Jamaica to show off his chops in 2011. Not even years of growing up around the culture could save that shaky patois. Still, it was his assertion that ting belonged exclusively to Toronto, and that the mainstream audience had him to thank for bringing it to the masses, that created the most problems. As a fan and fellow Torontonian, I rushed to defend what he could have meant, trying to provide context without sounding like a superfan, but I fell short each time.

In a 2015 interview with The Fader, Drake explained the controversy surrounding the song “Hotline Bling” sounding similar to D.R.A.M.’s “Cha Cha” by comparing it to the use of riddims, a single production used by multiple artists who then release their own singles. “You know, like in Jamaica, you’ll have a riddim, and it’s like, everyone has to do a song on that,” he told them.

That explanation doesn’t exactly stick, since riddims are a part of an entire system and culture of borrowing and battling to see which dancehall artists ends up with the most popular song from the same production. Credit is almost always given to the producer of the riddim, and it’s used largely as is, instead of being made into a derivative work. Though collecting royalties might be tricky, in dancehall the creative ownership cards are always on the table.

Even the very name of Drake’s imprint, OVO Sound, is a nod to Jamaica’s lasting sound-system culture, with his OVO Sound Radio stream on Apple Music regularly featuring mixes by reggae outfits likes Black Chiney and a healthy rotation of artists like Kartel and Chi Ching Ching. But Drake’s Jewish and American roots place him on the outside of that proverbial circle, which is where we find a slight disconnect.

Drake’s music may be a product of his environment, but he doesn’t have the best track record of giving credit where it’s due.

Drake’s music may be a product of his environment, but he doesn’t have the best track record of giving credit where it’s due. When dancehall legend Mr. Vegas made a seven-minute video expressing his frustrations with the use of dancehall on Views, I nodded in silent agreement. “You have Beenie Man as a intro man. You know what a intro man is?” he asked, referencing the talking cameo at the end of “Controlla” after sampling Beenie’s “Tear Off Mi Garment.” This criticism rang especially true when you consider that by the time the album version of “Controlla” was released, Popcaan’s verses had been removed. Recently, the announcement that soca star Machel Montano would be headlining the second day of OVO Fest alongside Beenie Man seemed to be a good place to start in terms of paying respects to his Caribbean influences.

Many cities in North America have a large West Indian population, but there’s something distinctive about how the community manifests itself in Toronto. Black American culture (with roots in the southern US) is still the undisputed default in most of the American cities where large numbers of Caribbean people live, like New York, Atlanta, or Miami. Even in the earlier stages of his career, Drake pointed to his summers spent in Memphis as an explanation for the slight Southern lilt in his rapping and speaking voice, something rappers in Toronto have had to do for years in a bid to gain larger global success. But in Canada, notions of blackness tend to be inherently linked to Afro-Caribbean roots, with 30% of the black population tied to Jamaican ancestry alone (alongside the rest of the West Indies and continental African identities). Jamaican culture has, in many ways, become part of Toronto’s mainstream culture.

Much of the city’s slang is steeped in patois. Words like ting, wasteman, and yute are unequivocally Jamaican but have also become important mainstays in Toronto vernacular. This doesn’t automatically give Drake, or anyone, the green light to make use of another culture at his convenience — particularly a culture that has been historically abused and vilified, even in a space where we have so much influence. The use of patois toes a precarious line between appropriation and appreciation, but in Toronto, culture is currency.

When mainstream artists borrow from reggae and dancehall without the proper attribution or paid dues, it’s reminiscent of the ways Jamaican labour has been used for centuries with little reward.

It’s not enough to simply say “Toronto has a lot of West Indians” as a way to rationalize the use of its cultural exports for profit by non-Caribbeans. And it’s still important to consider how the original creators of the works Drake samples or quotes are being erased in the mainstream. Jamaican culture is one of the most imitated on the planet, trailing closely behind American hip-hop in terms of global influence. Take reggae legend Junior Reid, whose single "One Blood" with rapper The Game dominated the charts in 2006. While Reid backed The Game on the promo trail in the United States, The Game was a no show when it came time to take to Jamaica. When mainstream artists borrow from reggae and dancehall without the proper attribution or paid dues, it’s reminiscent of the ways Jamaican labour has been used for centuries with little reward, lining the pockets of entities from corporations to entire empires. That might seem like a stretch for some, but the use of our culture is personal, and delicate, no matter how much “sense” it makes.

Aside from well-meaning donations that pale in comparison to the hundreds of millions of dollars these borrowing artists and their labels see, most of the revenue never touches Jamaican soil. Most of dancehall’s most popular artists, from Sean Paul to Aidonia, make the majority of their income touring abroad, where promoters are willing to shell out thousands of dollars more than they would ever make at home. The kind of infrastructure the dancehall music industry would need to keep the flow of dollars on the island is stalled by the lack of government support of the genre, and flat-out classism. So in those foreign spaces, these artists are the main attractions and, as such, are much more in control of their own value.

With Rolling Stone referring to songs like Rihanna’s “Work” as “tropical house” and attributing a dancehall resurgence to Justin Bieber’s “Sorry,” it’s time for West Indians to take better care in protecting the narrative around our music, in the same way that’s happening for other aspects of our culture. It’s also up to those shaping mainstream ideas and conversations to make space for those voice to be heard, and for non–West Indian artists to engage the full scope of our complex cultures instead of just painting something red, gold, and green and calling it a day.

Not everyone can try a ting on our watch.