When Bernie Sanders came to Washington Square Park in 2016, marijuana smoke filled the air. The rock band Vampire Weekend took the stage and sang a cappella. And actor Tim Robbins recalled coming to this same spot “as a young'un” to protest the Vietnam War.

If Sanders’ rally for a “political revolution” had echoes of the 1960s, then Elizabeth Warren’s gathering here for her own presidential campaign three years later felt like a different kind of movement.

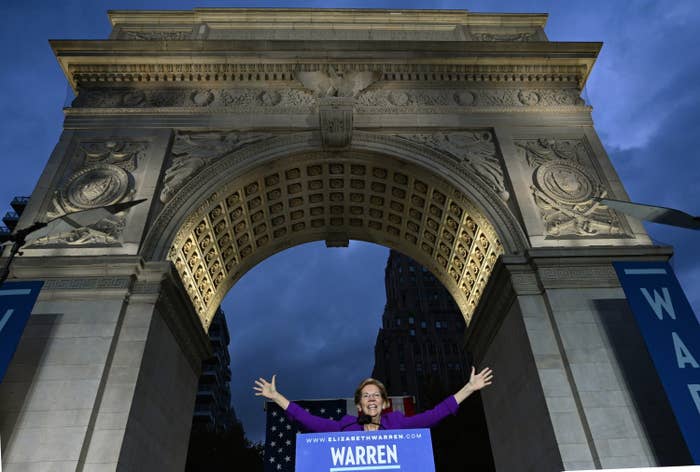

At the marble arches that stand atop this lower Manhattan landmark, a crowd of an estimated 20,000 people on Monday night wielded signs about “big structural change.” Introductory speakers told the crowd that Democrats didn’t just need the energy of a “blue wave” — but “a plan.” And Warren, invoking the story of the nearby factory fire that set off a wave of feminist activism in 1911 and helped lead to the New Deal, outlined a theory of change that combines movement-driven pressure “from the outside” with the tactical power of a leader working the system “from the inside.”

At her campaign events, the 70-year-old Massachusetts senator usually builds a case for her plan to fix a “corrupt Washington” around her on story: She talks about watching her family fall from the middle class in Oklahoma, learning words like “mortgage” as a kid, or about her career studying the root cause of bankruptcies, or fighting companies like Wells Fargo as a senator.

On Monday, Warren presented another woman’s story as the model for her movement for “big structural change.” Frances Perkins, the suffragist who would go on to serve as Franklin Roosevelt’s labor secretary and help advance the New Deal, witnessed the 1911 fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory just east of the park that killed nearly 150 garment workers locked inside, the vast majority of them women.

Amid an already growing movement over low wages and “dangerous and squalid conditions,” Warren told the crowd in Manhattan, Perkins went to Albany to lobby the government.

“Frances had a plan,” she said. “With Frances working the system from the inside, the women workers organizing and applying pressure from the outside, they rewrote New York state’s labor laws from top to bottom to protect workers.”

Sarah Peskin, the chair of the nonpartisan Frances Perkins Center in Maine, said Perkins was a notable political figure because she could both “build coalitions and serve as a brilliant tactician.” Warren supporters talk in similar terms about her work in Washington, where she has learned on grassroots organizations like MoveOn.org and the Progressive Change Campaign Committee to amplify her aims behind the scenes.

That combination — described by Warren on Monday as working the “political system relentlessly from the inside” while a “sustained movement applied pressure from the outside” — isn’t easy to sum up in a bumper sticker or on the debate stage. And Warren isn’t always as explicit about her aims as she was on Monday.

But it does separate her pitch from the other top two candidates in the race for the Democratic nomination.

Sanders, who launched a new wave of progressive activism with his primary challenge against Hillary Clinton in 2016, talks about himself as one of many people in a larger political revolution: No one politician, he says at nearly every event in his second presidential campaign, “can do it alone.” Joe Biden, the former vice president and US senator, is not selling a movement so much as his ability to work across the aisle and restore “normalcy” in the White House. Warren, in her speech, countered that idea.

“As bad as things are, we have to recognize that our problems didn’t start with Donald Trump,” she said. “He made them worse, but we need to take a deep breath and recognize that a country that elects Donald Trump is already in serious trouble.”

There were two signals of Warren’s strategy the morning before the speech: a new plan and a new endorsement.

The plan, a series of proposals to fight corruption, spelled out new rules that would dramatically change how lobbyists operate, how campaigns are funded, and how politicians disclose their own financial interests.

The endorsement came from the Working Families Party — the progressive activist group that backed Sanders in 2016 and could boost a Warren White House’s inside/outside approach. Maurice Mitchell, the group’s national director, introduced Warren Monday night.

Warren’s comparison between herself and Perkins was nearly explicit. (At one point, she referred to Perkins as “one very persistent woman,” a callback to an early tagline for Warren’s campaign). Her campaign reached out to Perkins’ grandson, Tomlin Perkins Coggeshall, who gave them barn boards from the Perkins’ homestead. Aides said they used the boards to construct the podium Warren used on Monday.

“We’re not here today because of famous arches or famous men. In fact, we’re not here because of men at all,” she said near the start of the speech. “We’re here because of some hard-working women.”

Monday’s speech — held four days after the last Democratic debate, at a time when Warren has solidified her status as a central force in the primary contest — marked a departure from Warren’s typical slate of smaller town halls. It was the first and only time she’s used a teleprompter at a campaign-hosted event since her official launch speech early this spring.

After concluding her remarks, as the crowd pushed in toward the Washington Square Arch, Warren still stuck around for her usual “selfie line.” She started her speech saying Monday night would be a little different than her usual town hall or speech. But the selfies would stay.

“Some things we just don’t mess with!”