In 2007, Andrew Norman Wilson worked as a contractor producing video for Google, where he noticed a strange thing: In the building adjacent to his office, workers would stream out every morning, as he arrived. They had worked a long night shift. He also discovered that these workers had a different classification than other contract workers such as himself. They weren't allowed to touch any of the standard Google amenities that you hear about in every fawning business profile: the free food, bicycles, etc.

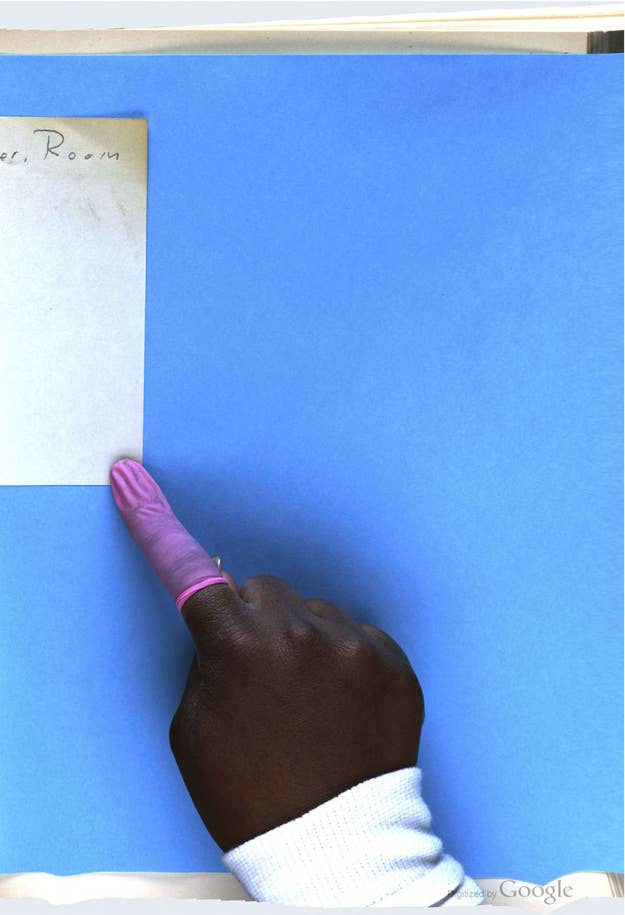

Wilson turned his video camera on the workers, who turned out to be Google Books digitizers. When Google found out, it fired Wilson and tried to destroy all of his footage. Despite fear of a lawsuit, Wilson put out a video (titled “Workers Leaving the Googleplex,” referencing early cinema’s “Workers Leaving the Factory” by the Lumiere Brothers) and it went viral.

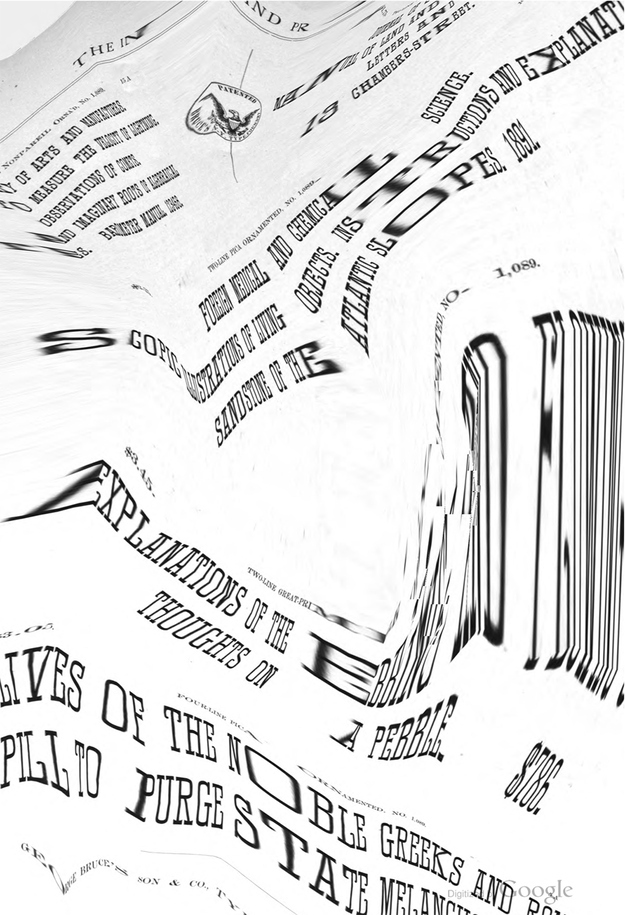

The Chicago-based artist has continued to explore the mostly-unseen labor behind Google Books, the eight-year-old digitalization effort that has resulted in 20 million-plus scanned pieces of text. For his latest project, ScanOps, Wilson collected hundreds of examples of Google Books misfires, focusing on instances of scrambled up pages, the inevitable consequences of the fact that workers are photographing thousands of pages a day — and it's those mistakes that mark what they're doing as human labor.

Wilson does not want to simply collect examples of Google flubs. “I’m not really interested in putting this project online,” he told me, “I want to re-materialize them as prints and a book.” By that, he means taking the digital image and putting it on paper, with a frame, to be shown as a photograph. Besides adding colored frames, he has not altered the images. He is showing some of the prints in art galleries and his book, to be published this summer, will contain hundreds of misfires.

“They have an aesthetic experience that exceeds the raw information, and evokes feeling," Wilson says of the pages, which occasionally turn out fluorescent, or with a worker's hand still visible, wrapped in pink finger condoms.

And how do you find examples of Google’s fuckups? Wilson recommends looking for old or scholarly texts — those are the ones that get far less scrutiny by readers and Google overseers. Sometimes, he said, he would find examples of Google Books mistakes on blogs, most notably, The Art of Google Books, a Tumblr devoted to marginalia and other flaws.

What is the point of all this? For Wilson, it’s the second of three projects focused on the human labor that has gone into Google’s dream of putting the world’s libraries online. (And it’s not just Google’s dream: a Carnegie Mellon professor’s Million Book Project was churning out 100,000 pages a day at 20 scanning stations in China and India according to the New York Times.

For his third act, Wilson said that he has been in touch with some Google Books workers and wants to tell their stories more directly. “I felt like I was in close proximity while working next to them, but that got cut off, obviously, when I got fired,” he said, “With ‘ScanOps,’ I was getting close to them again, but they remained anonymous. This will be appropriate closure, now that I have made contact.”

The larger issues swirling around his work though, remain. From the debates around the ethics of Apple’s supply chain to the outsourced drones at call centers abroad (and at home), the digital factory floor remains largely unseen.

Of course, this is nothing new. When I was on the phone with Wilson, I tried to look up one of the publications in which he found a finger, mostly because I was having trouble believing that the vivid colors were not added post facto. Scrolling down the pages of a 1912 issue of The Inland Printer, I found an ad featuring a giant pair of hands. “Human Hands,” it said, “should never be employed at a task which a machine can do as well or better…” The Google Books digitization logo rested at the bottom of the page. Seems that human hands have not been rendered obsolete yet.

Rhizome has a longer interview with Wilson as well, if you're interested.