Twenty-nine is a weird age. A hospice for youth. It’s the last guest to leave the party. Thirty gets all the attention — the big, round number feted with ritual debauchery and performative solemnity. We think of 30 as the closing of one door and the opening of another, an unambiguous transition into adulthood, for better or for worse. But this transition doesn’t actually happen at 30, which, like a memorial service or Valentine’s Day, signifies something it can’t encapsulate. The transition happens earlier, at 29, when the lights of childhood experience have gone too dim to guide you; when your wildest friends from college have been replaced by lookalikes in committed partnerships, posing in photos with baby bumps.

When I spoke to him in 2013 for Billboard magazine, Drake was 26 and still feeling his way toward the summit of his career. This was a month before the release of his last proper solo album, Nothing Was the Same, and he had recently turned that feeling — the sensation of being on a roller coaster lurching toward its peak — into massive chart and viral success with the album’s lead single, “Started From the Bottom.” As a narrative trope, “the come-up” is almost as old as hip-hop itself, undergirding both early ‘90s mafioso rap and the late-‘90s bling era. But no one has mined it more consistently or to greater effect than Drake, who sung of his own rise to power not only as a selfish enterprise but as if he were speaking on behalf of an entire generation of young people who happened to be coming of age on the same timetable. As a songwriter, this was his core value proposition. And he knew it.

“I do spend a lot of time when I'm writing, especially lately, trying to make something for people to live by,” he told me in 2013. “I'm trying to make anthems that are empowering to people … Some people fall into routines in life and stay stagnant. That just wasn’t the case in my life. My life’s been an uphill climb, and I just want to encourage people to make that climb."

Views turns a decisive corner into late-twenties ennui, when the giddy expansiveness of youth suddenly hardens into something more fixed.

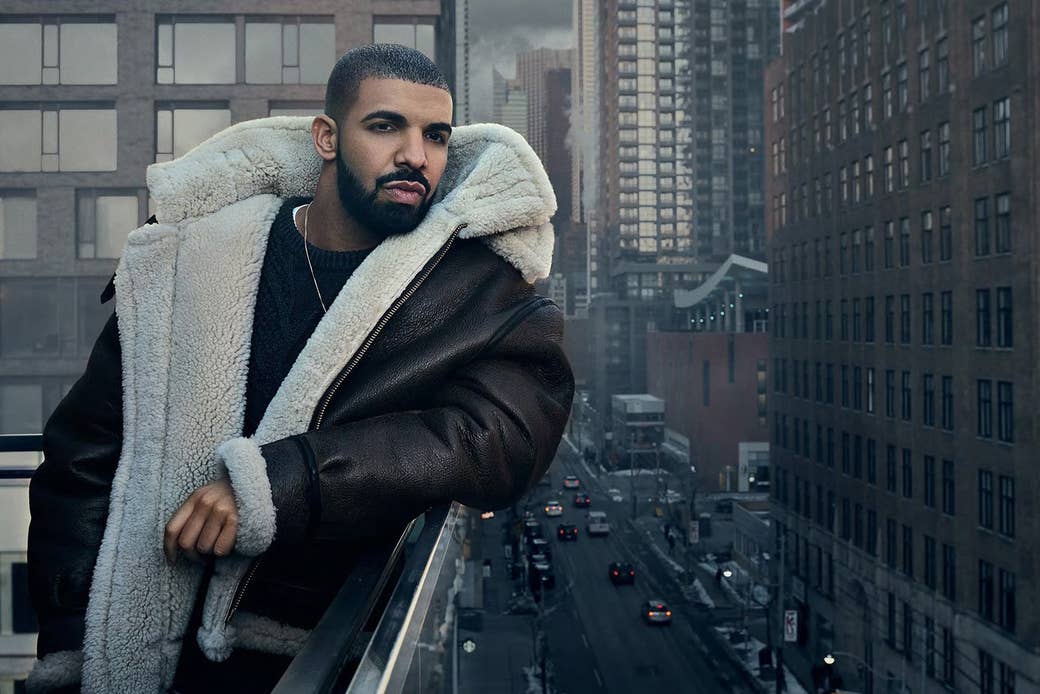

Now Drake is 29, and, like many great rappers before him, the dramatic trajectory of his climb has finally reached a plateau. On Views, his fourth and most recent solo album released on Friday, gone are the euphoric and incredulous musings of a neophyte with the wind at his back, nimbly bounding from one career milestone to the next. Drake has firmly occupied the top spot in hip-hop for years now, and in the place of songs about the come-up, Views offers something decidedly darker but ultimately no less human: an acrid and at times exhausting catalog of laments, reminding us that fulfilling your potential in life can breed its own kind of misery.

If his oeuvre stretching from the breakthrough 2009 mixtape So Far Gone to last year’s transitional If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late was about the joy and anxiety of checking off rites of passage (when it comes to work, money, and relationships) in your early and mid-twenties, Views turns a decisive corner into late-twenties ennui, when the tyranny of your own limitations begins to set in and the giddy expansiveness of youth suddenly hardens into something more fixed.

For Drake, who both predicted and, along with his idol Kanye West, catalyzed hip-hop’s turn away from tough guys and drug kingpins toward more internal and emotional dramas, a chip from his days as an underdog remains stubbornly lodged on his shoulder. His influence on rap radio and beyond is more palpable than ever (“A lot of n***as came up off of a style that I made up,” he rapped back in 2011), but he can’t bring himself to enjoy the fruits of the revolution he started, instead turning bitter at the prospect of sharing the spotlight. On song after song on Views, he wears his contempt for everyone outside of his immediate circle like an impenetrable cloak. “Your best day is my worst day,” he spits on “Weston Road Flows” (immediately followed by the hilarious misfire “I get green like Earth Day”).

This kind of me-against-the-world-ism is helpful when you’re on the outside trying to break in, but it becomes perversely malignant from the inside looking out. It leaves you paranoid and belligerent, marching off to battle after you’ve already won the war. Views lines like “I’m lookin’ at they first week numbers like what are thooose?” and “You platinum like wrappers on Hershey’s boy, that shit is worthless” would have been sportsmanly boasts three to five years ago. But it’s been a long time since anyone doubted Drake’s (increasingly peerless) ability to sell records, and his constant need to use this power as a cudgel against his rivals now reads as needlessly spiteful.

Drake at 29 is even more stunted when it comes to his relationships with women. His infinite string of romantic missed connections — spoiled by his unwillingness to either commit to a woman or let her go — has been meticulously chronicled on both songs and albums past; but on Views songs like “Redemption,” “Keep the Family Close,” and “U With Me?” he’s never sounded more callously indifferent about his shortcomings as a prospective romantic partner. These are the reflections of a man who has either become oblivious to his own faults or, more likely given his chronic self-obsession, has decided that the real problem is with everyone else.

Drake’s songs about women have always had shades of the needy (“CeCe’s Interlude”), creepy (“Make Me Proud”), and vindictive (“Marvin’s Room”), but their offenses were charitably excused by those who felt so inclined, first as the harmless grousing of a sensitive 23-year-old unlucky in love, and later, somewhat less convincingly, as the semi-legitimate brooding of a jet-set superstar who would be a great boyfriend if only his lifestyle would allow it. Drake himself gave cover to these interpretations by always sounding strangely wounded by the predicament of his celebrity, and convincingly horrified by the behavior it brought out in him. “I’m so sorry I’m so selfish,” he sobbed in the refrain to “Marvin’s Room.”

But on Views it’s Drake who is demanding the apologies. On “Redemption,” a song in which he delivers the lines “Run your mouth / I’d rather listen to someone else / I gave your nickname to someone else” and later chastises an old fling for having the audacity to end things after becoming a mother, he declares, incredibly, that it’s him who is owed mea culpas for Christmas. Such pronouncements are both alarmingly grotesque (from “U With Me?”: “I group DM my exes / I tell ‘em they belong to me / That goes on for forever”) and sadly predictable, suggesting that Drake’s unresolved frustrations with women as a younger man have metastasized over time. The longer it’s taken him to experience a successful romantic relationship firsthand, the more bizarre and unrealistic his notions of what one looks like have become.

These failures to evolve as a person, to sustain the remarkable rate of professional, emotional, and relational growth and change that characterize your early twenties through your thirties and beyond, are, of course, not unusual. We like to imagine people — particularly creative ones — as capable of infinite reinvention, able to conceive and inhabit new ways of thinking and being in the world on demand. But, if we're honest with ourselves, what usually happens is less glamorous: People grow up, settle down, and retrace a constellation of habits similar to the one that defined their formative years. “My life is a completed checklist,” Drake memorably rapped on Nothing Was the Same opener “Tuscan Leather.” On the Views track “Hype,” he revisits that idea from a different, even more somber angle: “I don’t know what else is left for me.” This makes his position sound more extraordinary than it really is. What’s left, even for Drake, is adulthood — for better or for worse.