Growing up in Puerto Rico, Christopher Gregory-Rivera has always been deeply engaged with issues around colonialism, which he said has “unequivocally reshaped the island — and many parts of the globe.” Most of his work looks at the territory’s history as a way to understand the present and attempt to unravel the forces behind the injustices that colonized and marginalized communities face.

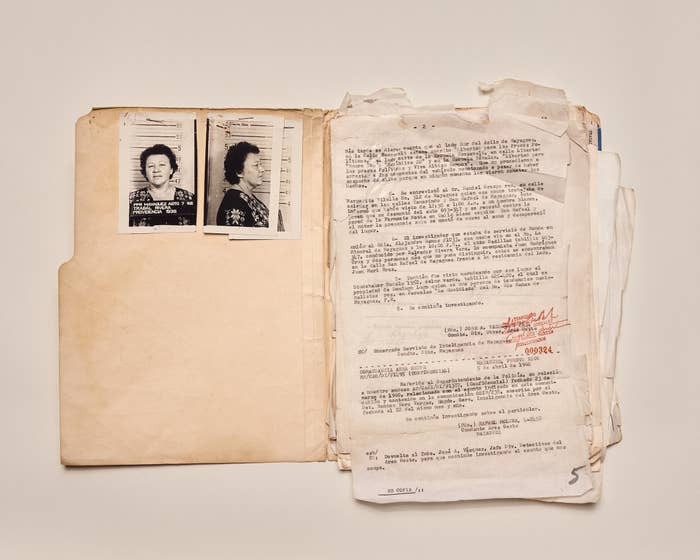

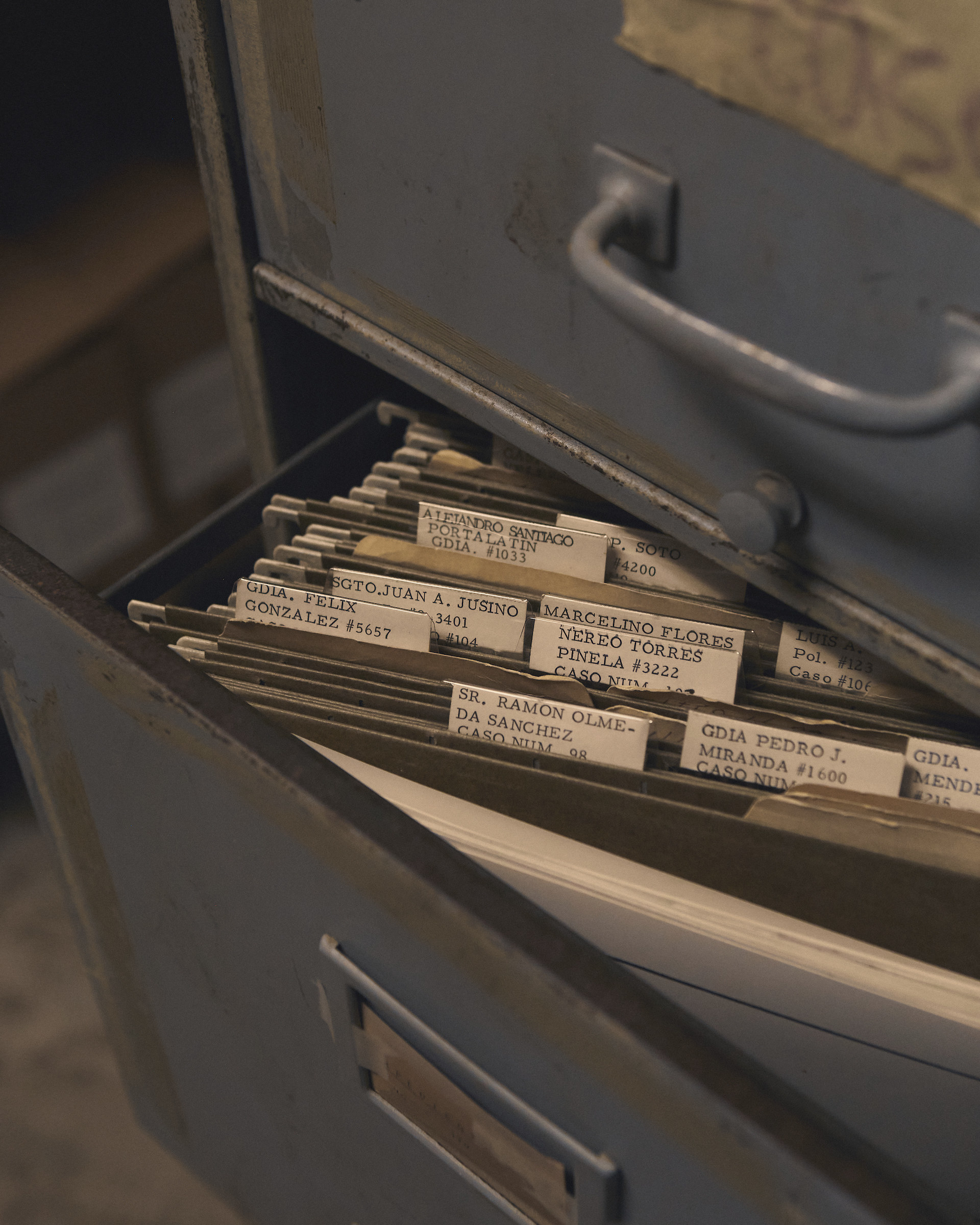

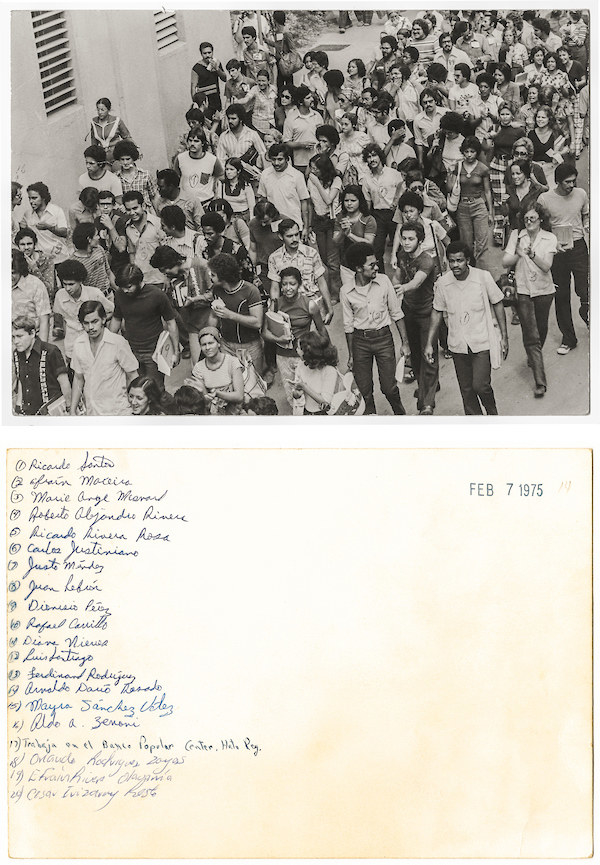

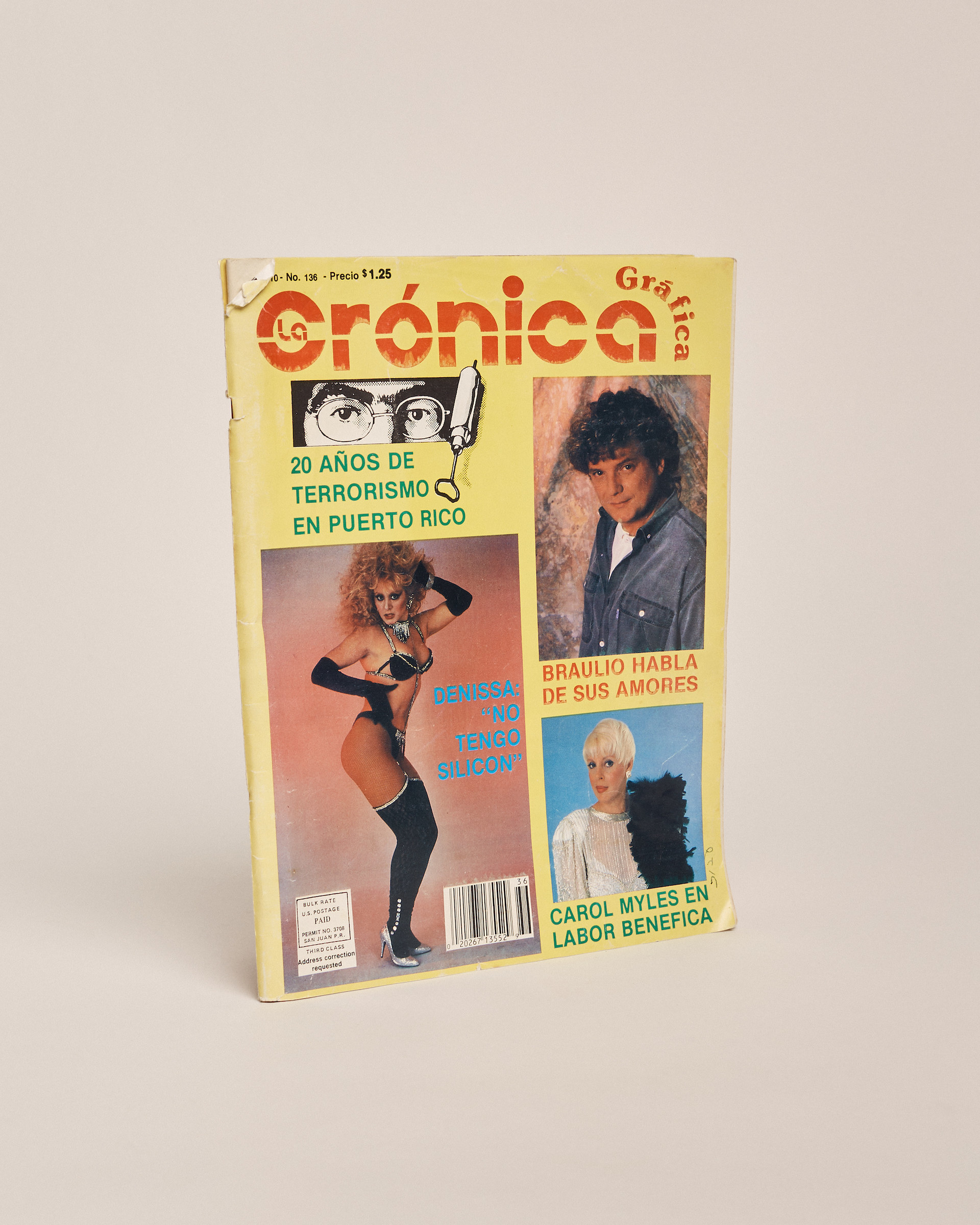

He began his photography career in Washington, DC. “I intimately experienced the way politics and power is crafted but grew increasingly disillusioned with the ability of political journalism to truly speak truth to that process,” he said. He kept this in mind for years before he saw his first “carpeta” (Spanish for “binder”), files on Puerto Rican residents compiled by a Puerto Rican secret police with the support of the FBI. The files targeted ordinary citizens who were suspected of aligning with the territory’s independence movement, whom authorities considered to be a political threat to US interests. Over the course of four decades, the FBI and the Puerto Rico Police Bureau maintained a secret network throughout the territory, “surveying, infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting” any national movements for independence by instilling a culture of fear, violence, and intimidation. This movement threatened the lives of ordinary citizens and political activists and turned national folklore into a real and ugly story of American colonialism.

Las Carpetas, an exhibition now on view at the Abrons Arts Center in New York, was curated by Natalia Viera Salgado, the current curatorial resident at the Abrons Arts Center, and the assistant curator at the Americas Society.

Tell me about the exhibit and the project, which you’ve been photographing for six years.

Christopher Gregory-Rivera: The project is a look at one of the longest continuous surveillance programs conducted by the US Government on its own citizens, which happened in Puerto Rico.

“Carpeteo” is what they called it — “to be foldered,” in the popular imagination in Puerto Rico. When I was going to protests for a variety of causes as a young photojournalist, my mom would always tell me to “be careful, te van a carpetear” — “they’re going to target you.” I always grew up with it.

After finishing internships and professional opportunities here in New York and DC when I was starting out, I thought about what long-term projects I wanted to do in Puerto Rico that were important. This stood out to me, and I started exploring it. And when I saw my first folder, it all became very real. I realized, this isn’t just a boogeyman or myth. It’s a very real thing that happened. The more I learned about it, the more I realized that this ties into why Puerto Rico is the way it is today. That gave me more momentum and energy to work on the project.

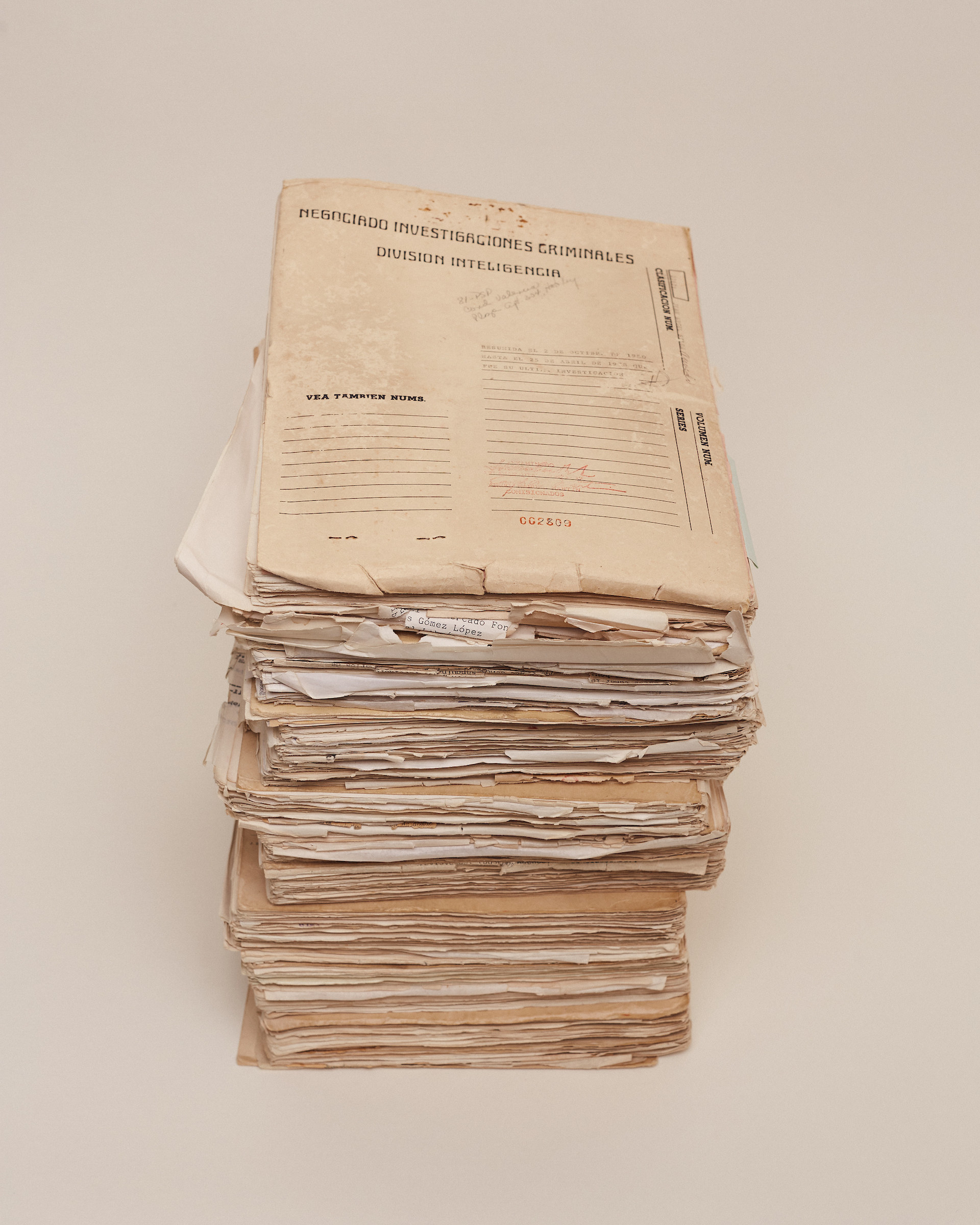

The exhibition is a collection of my still lives of the files and objects from the surveillance program as well as appropriation of archival photographs the police took or collected.

When the secret police were unveiled in 1987, the government was forced to return the files directly to those they had watched. It is the only case of original surveillance documents being returned directly to victims in the world. How did you access the files?

CGR: That’s a part of the conversation I like to have around this work, which is the archive and where people can access this memory, this history. Because the files were returned directly to people, I found my first one through word of mouth. Asking around, “Who has a carpeta?” The first one I saw was a university professor’s file. His surveillance file tracked thirty years of his life and was so big that he would wheel it into his classes on a hand truck to show his students. Through him, I kept asking around and finding more people that way.

There’s also an archive, which was made public a year after I started the project in 2014. It holds all of the folders or the files that the government of Puerto Rico was not able to return to people directly.

But that archive is fundamentally incomplete. You would either have to have been deceased or refuse to accept the return of your file for it to end up there. That’s part of why this history is not super present or understood, because these files were given to individuals. There was no process of collective remembering, just of individual remembering. There was no national understanding that this was something that the government of Puerto Rico and the United States did to the people of Puerto Rico. Rather, by not creating a comprehensive national archive and fragmenting the archive in the way the files were returned, it was made about individuals, which led to a collective process of forgetting.

It seems like some people are really open about their carpeta and others are embarrassed that they have one.

CGR: There are people who want to move on, who think that this was a dark period in history and they don’t want to relive it. There are people who feel it's a badge of honor. “The bigger the carpeta the better.” It shows how committed they were in supporting the independence movement. Some just choose to forget.

People who grow up with this, it’s dinner table conversation. It’s part of their family folklore, and for me it wasn’t. When I learned about the carpetas, I was very surprised and indignant that this happened. I had to wrestle with those feelings and the surprise I felt whereas for people who grew up with it, it’s perhaps closer and part of a generational process of healing.

The files contain reports of people’s day to day and political activities — but also photographs of them, mementos, and house plans, very intimate details of someone’s life.

CGR: Totally, and I was interested in including all of these in my project. The aesthetic choice of photographing on white is also a statement, sort of how I feel about surveillance in general. In 2013, I had been doing an apprenticeship at the White House and Capitol Hill for the New York Times, and the Snowden revelations had happened. And the conversations people were having around the issue of surveillance was something like, Oh, it doesn’t matter if the government is watching me; I have nothing to hide. I felt that thinking that way was particularly dangerous because of what had happened in Puerto Rico. The problem with surveillance is not the information that is collected; it is the chilling effect knowing you are being watched.

That is what the carpetas teach us. A lot of the information in them is nefarious and dark in the way it was collected, but ultimately none of it is incriminating. None of it is really that important, and a lot of it was actually made up. Informants would make money for reporting, and it became a type of cottage industry. The act of turning Puerto Ricans against each other and the carpetas themselves were the weapon against the government's political enemies. It wasn’t really about the information collected; it was about the fact that people knew they were being watched and the effect that psychology had on civil society, specifically on political speech.

The way I photographed the carpetas is often as stacks. There are some details, there are some objects, but I wasn’t necessarily interested in relaying that much information about what was in the files themselves, because in my mind it wasn’t really the point. The point was the fact that this had been made.

This was pre computers, so everything is carbon-copied. It’s typed, it’s handwritten. A lot of that texture was really interesting to me visually. These were so clearly made by hand on purpose, and there were so many people who were involved in making them. That’s part of its psychological weight.

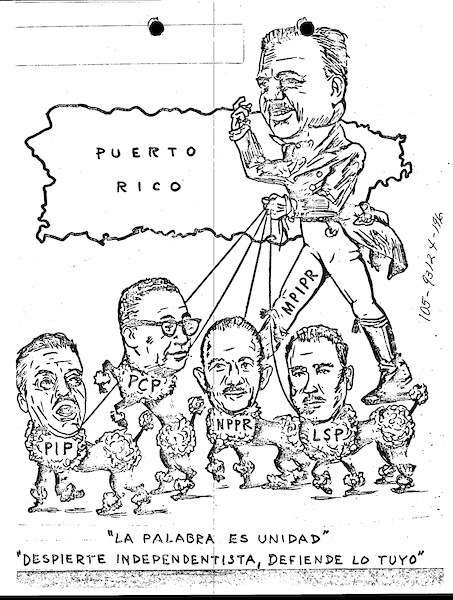

Natalia Viera-Salgado, Abrons Arts Center: I like the confiscated objects, actually. The choice is really interesting — the books that get confiscated, for example, and why they decided to keep them. The book on guerrilla warfare makes sense, the book on personal injury law not so much. I'm also interested in the absurdity of most of these fabricated stories. For example, this drawing or satirical cartoon. We don’t know who the artist was, but it was made to promote disunity among the pro-independence political movements which were many. The person who did this, their main purpose was to pit them all against each other.

“The cartoon was designed to hinder any unified action on the part of the independence groups and to create bickering in between them.” This was privately mailed by the FBI with instruction that the cartoon must not be able to be traced back to the bureau or any of its employees.

CGR: When people talk about this particular program, and there is so much polarization about the carpetas, especially in Puerto Rico, like, Oh, this is paranoia, this is a conspiracy theory. And for so many years, the people who were involved in the independence movement maintained that this was happening while society at large dismissed them. When it came out, what they had been saying all along was confirmed — but there was no collective acknowledgment of what had happened or an understanding of it. It’s important to note that the purpose of this show is not to support independence or any particular avenue of determination, but to show that Puerto Ricans did not have a chance to freely self-determine. If the decision was between independence, pro-statehood, or pro-commonwealth, one of those options was not viable because the United States and the Puerto Rican government made sure of that. As surveillance starts to disappear from its physical form and go online, how do we learn from this history going forward. I think there is a lesson here for us all.

What happens to the carpetas when people die? Is it completely up to the families?

CGR: Some people have donated them to universities or libraries or archives. I’m sure people lost some in the hurricane. It is an archive under threat, and it’s a history that, at least in my opinion, is important to unlock an understanding of issues around Puerto Rican identity and politics now.

Speaking of Puerto Rico’s identity, one frustration I’ve heard is about Americans’ fundamental lack of understanding about the territory’s relationship with the rest of the US. Has that changed at all in the last few years?

CGR: I would argue that many Puerto Ricans have a similar lack of understanding of the particulars of the relationship. There is just a fundamental lack of knowledge by a vast majority of Americans about Puerto Rican history and their own colonial history all over the world for that matter. But similarly many Puerto Ricans don’t know their own history. A lot of it has been controlled and manipulated by either the United States or the Puerto Rican government. This project aims to raise awareness in everybody.

Obviously this isn’t covered in school.

NVS: I never came across it, because I went to military school. All of the things that I know, it was from when I was growing up. It all happened outside of school. Going to university, I got to know the history, but I first became aware of it by moving to New York and working at an archive in Harlem at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College where I worked as part time while going to school and working in other art institutions. I worked there for four years and began to understand our history through primary sources. For example, I saw my first carpeta there. I was immediately intrigued. I spend a lot of my time trying to understand my own history and my curatorial perspective has changed a lot or has been guided by my interest in social justice and historical events. So in a way, a lot of these histories I learned through art, and moving towards building those relationships that intersect between politics, environmental justice, decolonial perspectives, etc. Moving from Puerto Rico to New York, working in Harlem and working with different curators and organizers, that’s where I learned about the Young Lords or the Black Panthers and began to understand and unpack a lot of things. And these experiences have informed my research and curatorial practice in profound ways.

How did your interests in political and social justice translate to the show?

NVS: I've known Chris for 10 years, and I’ve always loved his work. The first time I saw [Las Carpetas], I knew we needed to do an exhibition but wasn’t sure how or where. I saw it as an opportunity to merge art and pedagogy or history for example. It is places like the Abrons Arts Center, the Laundromat Project, Loisaida Center, Taller Boricua, and many other community-based organizations that are doing the work. And sometimes you can’t find this at big museums or institutions. I think we need to create while having a continuous dialogue with our communities. In a way, every time I have an opportunity to do an exhibition it is these topics that I want to put on the forefront.

CGR: Awareness, first and foremost. I hope my work is not didactic but rather highlights a systemic issue or the particular histories that reveal the root of issues facing particular communities today. The aftermath of colonialism is something I think many people will live with for generations to come — but the more we spend time on understanding how and why it happened and its effects on society today, the faster we can address those issues in ways that are truly impactful.