The food industry's big new themes are healthy eating and organic production, and so not a fried egg, strip of bacon, or piece of sausage was in sight during the Wall Street Journal's breakfast interview Monday with Denise Morrison, who's now well into her fourth year as chief executive of the Campbell Soup Company. Instead, the roughly 115 guests who gathered at the Essex House hotel off Central Park South in New York to hear Morrison speak were served sensible plates of fruit and granola to go along with their morning coffee.

The other thing mostly missing from the breakfast interview was any meaningful discussion about soup, which was mentioned only minimally relative to its importance to Campbell's business — soup sales accounted for about 30% of its overall $8.3 billion in sales during its 2014 fiscal year, which ended on Aug. 3.

"Soup is a vital product and an economic engine for us," Morrison said, in response to a question during the Q&A portion of the interview, "but we are definitely more than just soup."

When Campbell reported its fiscal 2015 first-quarter earnings just before Thanksgiving, it said U.S. soup sales increased 6% for the three months ending Nov. 2, just the second time that has happened in 15 months. But there was no backslapping among executives or Wall Street analysts. The gain was a false one: The boost occurred mostly because big retailers like Wal-Mart — which ranks as Campbell's largest customer, accounting for just under 20% of its net sales — made their Thanksgiving and Christmas holiday orders earlier than usual.

The reality is that soup sales overall, and for Campbell in particular, have softened since 2009. According to Chicago-based market research firm IRI, annual soup sales in the U.S. haven't grown by more than 2% since 2010.

Campbell's soup sales have mirrored or underperformed the overall market, according to IRI data, falling every year — 2011 saw the biggest drop in dollar sales, of 4.3% — except 2013, when sales grew 2.7%. So far, through the 52 weeks ending Nov. 2, overall soup sales overall have declined 0.5% to $5.9 billion, with unit sales dipping 2.1% to 4.5 billion. Over the same period, Campbell has seen soup sales decline 1.8% to $2.6 billion, with unit sales dropping 2.7% to $1.7 billion.

While certain niches of the soup industry are growing, such as premium and organic soups, the big-money categories such as condensed and ready-to-serve are struggling. Macroeconomic factors well beyond Campbell's control are to blame, from a shrinking U.S. middle class and high unemployment to shifts among consumers toward organic and fresh food options and greater demand for transparency in how food is produced and prepared.

Over the last five years, Campbell's revenue has increased to $8.3 billion from $7.7 billion, but it has also acquired three companies that have added roughly $1 billion in sales to help goose its revenue figure. Its net earnings have steadily declined during that time frame as well, from $844 million in 2010 to $818 million in fiscal year 2014.

"We continue to see canned soup as a share donor over time," wrote JPMorgan analyst Ken Goldman in a research report about Campbell's first-quarter 2015 earnings.

Put another way, Goldman thinks that soup — in particular, the condensed kind in those red-and-white cans Andy Warhol made iconic — is a business that will grow little, if at all, for Campbell. He's not alone in his view — many other analysts who follow Campbell share his opinion. Even the company's own executives are pragmatic about the long-term outlook for soup.

"Sales in our core soup business did not meet our expectations," said Mark Alexander, president of Campbell's North American business, during the company's annual shareholder meeting in July. "While we are competitive again this year from a market-share standpoint, we failed to drive category growth and this is an imperative going forward."

There is, however, another, equally important imperative for the company — figuring out how to diversify away from soup into higher-growth areas as quickly as possible. Campbell doesn't want to be the food industry's version of a record label, stubbornly reliant on the sales of one product and dangerously ignorant of how it's being overtaken by newer, better, more consumer-friendly ones. That's why since 2012, Campbell has spent just under $2.2 billion buying companies that have absolutely nothing to do with soup. Its new tagline is "Real Food That Matters for Life's Moments." Food. Not soup.

To be sure, when asked at the Journal breakfast Monday if Campbell would consider dropping "soup" from its name in the future, Morrison didn't dismiss the notion outright. She hedged, and even hinted, that such a move may not be so far-fetched.

"Soup is our middle name," Morrison said, before adding that in the future Campbell will "behave our way into what we are called."

Morrison, the 60-year-old to whom the challenge of transformation has fallen, is a company veteran who took over as Campbell's CEO in August 2011 with a mandate to reinvent it. The New Jersey native and Boston College alum was recruited in 2003 by her predecessor, Douglas Conant. She is just the 12th CEO in the Camden, New Jersey, company's 14-decade history.

According to a Bloomberg Businessweek article at the time of her appointment, Morrison was the safe, predictable choice. She had a stellar consumer-packaged-goods business pedigree, complete with stints at Pepsi, Nestlé, Nabisco, and Kraft, before coming to Campbell, where she started her ascent up the corporate ladder as head of global sales and steadily rose up, becoming the company's U.S. president, senior vice president for North America, and chief operating officer.

But reinventing a nearly century-and-a-half-old company apparently takes time. The business narrative for Campbell is not much different today than it was in 2011.

"Americans seem to have maxed out their appetite for soup," read the Bloomberg Businessweek story, which also said that Morrison's plans as CEO included "more consumer advertising and brand-building, ramped-up efforts in emerging markets, and new recipes aimed at millennials," as well as "increased focus on soup for cooking, with cool iPad apps for recipes."

"They are in turnaround," said Erin Lash, a senior equity analyst at Morningstar. "She is working to reignite the company in dominate categories, as well as enhancing other areas of the business. So far, results have been slow, there hasn't been sustainable improvement."

Campbell officially incorporated as a company in 1922, seven years before the start of the Great Depression. But its lineage traces back even further, all the way to 1869, 145 years ago. The condensed soup that bears its name is as identifiable a part of the American family dining experience as McDonald's and Budweiser. Campbell's soup is used in more than 94 million homes in the U.S., with condensed soups found in 65% of those households, according to the company. Its soup and simple meals unit generates $3.6 billion in retail sales annually, with condensed soup accounting for $1.35 billion of that amount.

But times have changed.

"The food industry has had a tumultuous year," Morrison said in her address to Campbell's shareholders during its investor day in July. "It has been a year marked by a persistently challenging consumer environment and by an unmistakable decline in the industry's performance."

Actually, the tumult for Campbell — and the packaged food industry generally — dates back to the beginning of the end of the financial crisis in 2009. That's when middle-class families in the U.S., so squeezed by the Great Recession brought on by the subprime mortgage meltdown, were supposed to emerge to spur the economy with renewed spending vigor. Except that never happened — instead, there were continued high rates of joblessness, soaring health care costs, and declines in government assistance for poorer families, among other factors, have resulted in a general climate of spending anxiety among the middle class. Families are looking to save rather than spend wherever possible, and if they don't need something, they aren't buying it. With respect to food purchases, that dynamic is reflected in the fact that sales at dollar and club stores are growing at a faster rate than traditional grocery stores.

Campbell, not unlike McDonald's and Budweiser, also has a bit of a problem with younger consumers, whose shift in food-buying decisions came when the company's healthy and organic product pantry was empty. Twentysomethings are more conscious of their food-buying options than previous generations, and they are increasingly making decisions based not just on how healthy something is, but also where and how it is grown, produced, and even marketed. A recent study by the International Food Information Council found that about 40% of twentysomethings are in favor of more nutritional information on food labels — well above the percentage for other demographics — and 20% of them would pay more for sustainable products. They would rather have fresh, packaged fresh, or organic than frozen, canned, or condensed food.

"Overall, packaged food companies are being challenged from consumers looking for healthier options across the board," Lash said. "They want to eat healthier but don't want to feel like they are on a diet, so they aren't buying low-fat, low-sodium substitutes."

This consumer transformation "has been building for a number of years and now appears to be at or near a tipping point in terms of its impact on the industry," Morrison said at Campbell's investor day.

As is often the case, change driven by the twentysomething generation involves not just the goods being purchased but also the method used to buy them, which is to say that digital disruption is finally coming to the food industry. Or at least, companies are bracing for it.

According to digital research firm eMarketer, e-commerce sales are estimated to account for $347 billion of the $4.9 trillion in U.S. sales expected for next year. By 2018, those figures are expected to grow to $492 billion and $5.5 trillion, respectively.

But the food and beverage category is only expected to account for $8 billion of the $347 billion retail e-commerce total in 2015, and $11 billion of the $492 billion total in 2018, making it one of the smallest categories of online retail. Looked at another way, however, what that means is that food and beverages are ripe for e-commerce growth.

"Companies such as FreshDirect and Peapod have staked out a niche market for digital sales of food and beverages, and more recently, AmazonFresh and Wal-Mart have joined the online grocery competition," eMarketer wrote in its U.S. Retail E-Commerce: 2014 Trends and Forecast Report in April. "Additional fulfillment options could increase the penetration of e-commerce in sectors that to this point have lagged behind others."

Morrison, who speaks as if she just rolled off a CEO assembly line — she peppered her conversation with buzzwords, including "accelerating growth," "create shareholder value," and "platforms" — called the potential growth of digital food shopping a "tidal wave that is going to hit the beach real soon."

On Feb. 15, 2013, Warren Buffett, one of the richest men in the world and among the most lauded investors on Wall Street, announced that his Berkshire Hathaway investment firm and Brazilian private equity firm 3G Capital were buying Heinz, the American ketchup empire, for $23 billion. Buffet is known for his faith in well-known American brands — his investment firm's holdings include everything from Dairy Queen and See's Candies to Geico and Fruit of the Loom — and the fact that he was participating in the deal signaled to investors that perhaps food companies with similar attributes might become future acquisition targets.

By Feb. 22, shares of Campbell were trading above $40, a notable achievement since that plateau hadn't been reached since 2007. Even more notable is that the company's stock has pretty much traded above $40 per share since then. Campbell's stock closed trading Monday at $44.15, up 50 cents, or 1.2%, for the session.

The reason: Investors are thinking, or perhaps hoping, that someone buys Campbell. It wouldn't be the first time — Campbell has been mentioned as a takeover target every few years since 1989.

"We continue to believe that takeover speculation will provide a floor for the shares standing around this level," wrote Stifel Nicolaus analyst Chris Growe in a recent report on the company, adding that the potential for a deal "provides a level of support against challenged fundamentals that currently characterize the business."

The potential for a Campbell deal has also been heightened by the increase in activist investor interest in the food sector, from Starboard Value's takeover of Olive Garden-owner Darden Restaurants to Nelson Peltz's agitating against Pepsi. Morrison ducked a question about the possibility of activist investors making a run at Campbell during Monday's breakfast, saying that they typically look at four areas to attack a company — operations, capital, portfolio allocation, and governance — and on those areas, her and her management team "are our own activists."

Somewhat ironically, a funny thing happened almost as soon as Morrison took over as Campbell's CEO: She started buying up companies. In July 2012, a month before Morrison's one-year anniversary at the helm, Campbell announced it was buying Bolthouse Farms for $1.6 billion as a way to expand into the high-growth package fresh food market, which the company says is an $18 billion segment.

Less than a year later, in May 2013, Campbell said it would pay $249 million to acquire Plum Organics, a maker of organic baby food popular with twentysomething moms. A month after that, Morrison made yet another deal, this time spending $331 million to buy Denmark-based biscuit and snack company Kelsen Group. Combined, the three deals totaled just under $2.2 billion. The run of deals was unprecedented in Campbell's history: The last deal one of its brands did was in 2009, when Pepperidge Farm bought Ecce Panis — Campbell itself hadn't made a deal since 1998.

Morrison felt she needed a "trio of growth engines," as she calls the acquired companies, because they serve the dual purpose of decreasing Campbell's reliance on soup and expanding its international sales presence and health and well-being products consistent with consumer preferences.

Bolthouse is "inspiring the fresh revolution," Campbell proclaimed in its 2014 annual report, with super-premium health drinks like Dairy Greens and 100% Pomegranate, snack packs that include fresh, peeled baby carrots, and salad dressings like Cilantro Avocado and Mango Chipotle that are about 40 calories per serving.

Plum, according to the news release announcing the deal, is the No. 2 brand of organic baby food in the U.S. and fourth brand overall in the baby food market, a $2 billion market where the type of products Plum makes — among them squeezable fruit and veggies concoctions called Mashups — are the fastest-growing part.

While the American middle class is shrinking, the Asian middle class is expanding, with some reports saying that by 2030 two-thirds of the global middle class will reside in the Asia-Pacific region. That's where Kelsen comes in: 40% of its sales come from China and Hong Kong.

The U.S. still ranks as Campbell's largest market by a large margin, however, with $6.4 billion of its $8.3 billion revenue total in 2014 coming from America. Currently about 22% of the company's revenue is generated from international markets, with Australia, where its Arnott brand crackers are favored, accounting for $709 million and other countries making up the remaining $1.1 billion. Morrison said that around 70% of the growth in the food market going forward will come from emerging markets.

Combined, Campbell says the three deals contributed more than $1 billion in sales during 2014, with Bolthouse accounting for $756 million, Kelsen $193 million, and Plum $88 million.

Parallel to her dealmaking, Morrison has also been restructuring Campbell's operations — or "rightsizing" them, in corporate speak — by selling underperforming operations such as its European soup and simple meals business, closing plants, and moving the company to an automated packaging system.

Roughly 2,335 jobs will have been eliminated from 2011 through fiscal year 2015, according to the company's annual report. Morrison said Campbell has closed 10 manufacturing plants and reduced its global workforce by 10% since 2007, for an annual savings of $186 million. Overall, Campbell's workforce is at about 19,400 globally today, up from 17,500 in 2011, with about two-thirds of its staff in the U.S.

But the deals have had an impact on Campbell's overall profit margins. The company is still making money — it recorded net income of $818 million on $8.3 billion in revenue — it is just doing it less profitably. The frenetic deal-making has also increased Campbell's debt load to $4 billion from $2.8 billion in 2010.

"This will mark the fifth year in a row of gross margin declines," wrote Credit Suisse analyst Robert Moskow in a report after Campbell's first-quarter earnings in November. "While we agree with management's strategy to improve the growth profile of its portfolio by de-emphasizing soup and expanding into 'packaged fresh' products to attract millennials, the negative impact on the company's gross margin structure remains a concern."

And Morrison's buying may not be over — she readily admits that continuing to diversify the company may require further acquisitions, though she dismisses criticism that she hasn't moved fast enough since becoming CEO. She said potential future acquisitions would likely come in the health and well-being or international biscuits markets.

That may be why investors are feeling less and less optimistic about someone buying Campbell. According to a report in Forbes, Campbell is one of the most heavily shorted stocks in the S&P 500 index, meaning investors think its shares will decline over time rather than increase. It ranked seventh as of Oct. 31.

"I doubt they will be bought in the near term," Lash said.

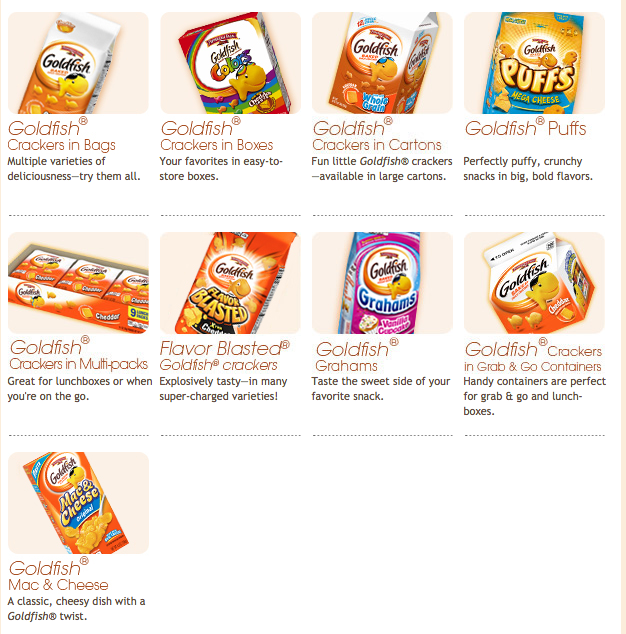

If Warhol were to chose an iconic Campbell product as a means to insult the high-regard abstract impressionists hold themselves in today, he might go with its Goldfish snacks instead of soup cans. Goldfish has remained incredibly resilient to macroeconomic trends and shifting consumer preferences, with Campbell saying that 2014 marked its 10th straight year of retail sales growth.

Goldfish is one of 11 "power brands" that sell more than $100 million annually for Campbell. Swanson, Prego, Pepperidge Farm, V8, and the newly acquired Plum and Bolthouse Farms are among some of the others.

That's why, in addition to buying companies to enter new product categories, Campbell is also focusing on extensions for its most popular brands. That means extending V8 to include chocolate-flavored protein bars and shakes and more juice combinations, such as Carrot Mango and Purple Power, because, as the company's President of U.S. Retail Sales Ed Carolan declared at its investor day in July, "Veggies are on trend and we believe the craze is here to stay." Or expanding the Campbell's brand from soup to include skillet, slow-cooker, and dinner sauces, a $100 million market that has arisen from consumers who want to cook but don't have the time. (Campbell's internal research found that 70% of home-cooked dinners were planned within an hour of eating.)

In total, Campbell plans to launch more than 200 new products in 2015.

While Goldfish continues to be a favorite of parents with toddlers (it is, on a personal note, my daughter's daily after-nap snack), more than one-third of its sales are in households without children, according to Campbell's research.

The company also found that teens viewed Goldfish snacks as bringing them "comfort and reassurance from their overscheduled lives." As a result, Campbell created Goldfish Puffs and plans to aggressively market to teens through such things as being a sponsor of the Z100 Jingle Ball in New York City. Over the summer, Campbell also launched two new flavors of Goldfish, Screaming Hot and Zesty Chili Lime, aimed at the Latino community, and last year launched Goldfish-branded mac 'n' cheese.

The activity around Goldfish underscores how Campbell's focus is on putting research, marketing, and promotional dollars behind products other than soup that have the best chance to drive growth.

Whether Morrison can successfully reinvent Campbell depends on how much buy-in her turnaround plans get from twentysomethings. The company has done extensive outreach and research on the young adult cohort, setting up a team within its consumer insights group that it sent out to shop, cook, and even go to bars with them.

"They had so much fun, I couldn't get them to come back to work," Morrison said of the research team, which is made up of twentysomethings.

A page on Campbell's website is devoted to "connecting with the next generation" and invites consumers to connect with Morrison on LinkedIn and follow her on Twitter under the hashtag #CEODenise, neither of which are exactly in tune with how twentysomethings use those platforms or social media in general.

Morrison also runs a leadership bootcamp dubbed "Camp Campbell" that aims to mentor and inspire young female workers on entrepreneurship and navigating the climb up the corporate ladder. The camp currently operates in 10 cities, from Boston to Dallas to San Francisco, and features 12 mentors and more than 60 female members.

It also means creating what Morrison calls a "digitally fit company." Financially, that means Campbell now devotes about 20% of its overall advertising budget to digital, where its goal is to not just produce advertising but "content" that works on multiple screens and engages consumers with its brands.

At Goldfish, where Campbell plans to increase advertising spending on the brand alone by 20%, promotional campaigns are built around its Finn character, who is used as a central figure in digital stories in online games and apps that "address real-life challenges that children face every day."

Campbell's efforts to diversify, however, are just in their infancy; soup sales still account for the overwhelming amount of the company's financial production.

According to Stifel Nicolaus' Growe, they account for about 70% of the revenue from the company's U.S. Simple Meals division, which itself made up $2.9 billion of the company's $8.3 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2014, or about 36%.

And Campbell is still as dominant in the soup market as Google is in search advertising, with its share of the U.S. "wet soup" market over the last 52 weeks coming in at 59%. (Private label, or store-branded, soups accounted for 13% of the market, and other branded soups like Progresso for 28%.)

"The U.S. soup business remains the linchpin to improving growth prospects for the company. This category has struggled the past several years and while we have seen some signs of life (stabilization at least) we believe the growth prospects for the category remain muted," Growe wrote in a recent report.

Not all soups are created equal, and under the broad umbrella of "soup" there are many different varieties — from broth and ramen, to condensed and bouillion, to premium and organic — some of which are growing and some of which are not. For example, according to IRI, dry broth and stock sales have increased 7.7% to $71 million for the 52-week period ending in November, while sales of ready-to-serve wet soup have declined 2.2% to $1.9 billion.

Campbell's performance mirrors the soup market's overall trends. While its Swanson-brand broth experienced sales growth in 2014, it was offset by declines in ready-to-serve (i.e., canned and microwavable) and condensed soup. More specifically, according to the company's annual report, condensed soup and ready-to-serve soup sales in the U.S. decreased by 3% and 6% respectively in fiscal year 2014. Broth sales, by contrast, were up 8%.

As Campbell has lost market share in recent years to intense competition from old rivals like Progresso and newcomers like Amy's Kitchen, it is redoubling efforts to enhance its offerings, particularly in faster-growing parts of the market such as premium, organic, and international. The company this year is launching its first line of organic soups and introducing Mexican and Latin-inspired flavors such as Creamy Poblano and Queso.

Premium and "indulgent" soups, which account for $750 million of overall soup sales and are growing at a rate of 12% annually, are among the biggest opportunities for the company. Campbell's executives have called expanding into these areas a "strategic priority." It has leveraged its Chunky brand, which generates more than $500 million in sales for the company, into a new line of "pub-style" flavors, such as beer and cheese and chicken pot pie, which have scored with the "men drinking beer and watching football at home" set. And it has honed in on twentysomethings who view soup as a meal unto itself with its Slow Kettle and Go! brands.

Still, despite all the new products, Growe estimates that Campbell's U.S. soup business will grow by just 1.5% this fiscal year.

"Campbell's goal of stabilizing this business has been met, but accelerating its growth remains challenging," Growe said in his report.

That's why Campbell's ultimate goal is to be more than just soup.