TORONTO — It began with a solo rendition of "O Canada" by Kate Hays, a sports psychologist. Then a choir of other psychologists responded in harmony with "The Star-Spangled Banner."

For a meeting of a scientific organization, it was an unusual patriotic spectacle — but, perhaps, an apt one. Psychologists are gathered here this week to debate an ethical crisis stemming directly from their profession's ties with national security agencies.

It's the first meeting of the American Psychological Association (APA) since the release of a devastating independent report on its role in facilitating the abuse of detainees in the "war on terror." The APA's governing Council of Representatives has to pick up the pieces and plot a new course for the organization.

"We start this process of making the world a better place here in this room," APA president-elect Susan McDaniel, a family psychologist at the University of Rochester in New York, told the council. The task, she said, was "to reset our moral compass and be certain we're headed in the right direction."

Judging from the chaotic progress of today's council meeting, that's going to hard to achieve.

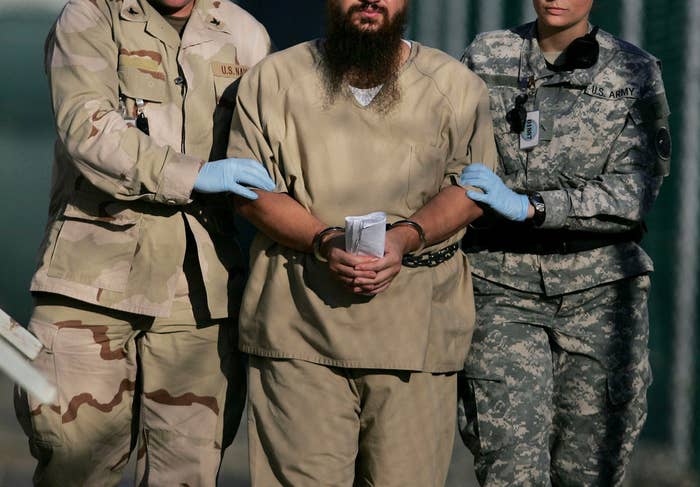

The full horror of the "enhanced interrogation" techniques employed by the CIA during the administration of George W. Bush were laid bare last year in a Senate Intelligence Committee report. Among other abuses, detainees were waterboarded, deprived of sleep, subjected to extremes of temperature, and forced to maintain painful "stress positions."

Similarly harsh methods — minus the waterboarding — were used by the Department of Defense at the Guantánamo Bay Detention Camp.

Facing a barrage of criticism over its handling of concerns about the involvement of psychologists in these interrogations, the APA asked David Hoffman, a Chicago lawyer and former federal prosecutor, to investigate.

Hoffman's report, released last month, concluded that the APA's leaders wanted to "curry favor" with the military and the CIA and colluded with the Pentagon to issue "loose" guidelines that would not curtail interrogations — while at the same time trying to convince the public that it was concerned about ethical issues.

These revelations strike at the heart of psychology's status as one of the healing professions. "This is the biggest bioethics scandal since the Tuskegee syphilis study," Stephen Soldz of the Boston Graduate School of Psychoanalysis, one of the APA's fiercest critics, told BuzzFeed News. He was referring to the infamous experiment in which black men in rural Alabama were left untreated for decades to see how the disease progressed.

In the weeks leading up to the Toronto meeting, nobody was sure whether the event would bring catharsis and healing or an escalating crisis for psychology.

"We've got a fire in our house, and it's a devastating fire," Michael Wessells of Columbia University in New York, who studies the psychological impacts of war and political violence, told BuzzFeed News.

The 542-page Hoffman report is damning.

After interviewing 148 witnesses and sifting through 50,000 documents, including lengthy email threads, Hoffman concluded that "APA wanted to foster the growth of the profession of psychology by supporting military and operational psychologists, rather than restricting their work in any way."

Hoffman's report described the military as acting like a "rich, powerful uncle" to psychology, boosting the influence of a profession that has often seemed overshadowed by the medical doctors who practice as psychiatrists.

At the center of the fight is the APA's Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security (PENS), which in 2005 was asked to judge whether psychologists involved in military and intelligence work were getting "adequate ethical guidance." By then, a leaked report from the International Committee of the Red Cross had accused U.S. military interrogators at Guantánamo of methods that were "tantamount to torture."

The nine-member PENS task force was stacked with six psychologists with military connections and carefully managed by APA officials to ensure that its report, released in June 2005, wouldn't displease the Pentagon, according to Hoffman. His report states that this effort was led by APA ethics director Stephen Behnke, who was in regular contact with Morgan Banks, lead psychologist with the U.S. Army Special Operations Command.

The three members without military connections were sidelined, and their efforts to prohibit psychologists from involvement with specific harsh interrogation methods swiftly rejected. One of the dissenters, independent social psychologist Jean Maria Arrigo, later turned whistleblower and released notes of the task force's confidential deliberations to the investigative journalist Katherine Eban — who wrote about psychologists and torture in a 2007 feature for Vanity Fair.

Wessells was another of the dissenting minority. He signed on to the task force report only after being assured by Behnke that it would be followed by a "casebook" detailing exactly what psychologists could and couldn't do. In 2006, with no sign of the casebook appearing, Wessells resigned from PENS in protest.

It wasn't until 2011, according to the Hoffman report, that a deliberately vague document — far from the promised casebook — was "snuck into a corner of the APA website with the fervent hope that it would be entirely ignored."

The @APAConvention begins tomorrow in Toronto. What are you most looking forward to at the event? #APA2015?

#APATorture is a scandal of historic proportion that has severely damaged APA & tainted an entire profession http://t.co/5t1qoba4mi #APA2015

Timid @APA Board praises 3 leaders ousted due to #torture scandal. Bad move. We need truth, courage & accountability. http://t.co/K2KNc8YAhT

After years of denials, the Hoffman report has stung the APA’s leadership into action.

Behnke was quickly removed as APA ethics director. In a statement issued through his lawyer, former FBI Director Louis Freeh, Behnke rejected the report's conclusions as "a gross mischaracterization of his intentions, goals, and actions."

The statement suggested that Behnke had been made a scapegoat: "It is unconscionable that APA would take action against Dr. Behnke on the basis of allegations that are fraught with defamatory material."

Three more senior APA officials have since stepped down: chief executive Norman Anderson, his deputy Michael Honaker, and Rhea Farberman, the association's head of communications.

Now the APA's leadership is backing reforms including an outright ban on its members participating in interrogations of people held by the military or intelligence authorities.

In doing so, the APA board has embraced the main demand of Arrigo and other dissidents. It's a remarkable turnaround, given that the two camps have spent a decade in open conflict over allegations that some psychologists were complicit in torture.

APA past president Nadine Kaslow, a clinical psychologist at Emory University in Atlanta, today sent a clear signal, wearing a large red button bearing psychology's "Ψ" symbol and the phrase "First, Do No Harm."

But it was hard, for much of the day, for outsiders to judge how much had really changed.

Until the public and press were admitted shortly after 2 p.m., most of the council's deliberations took place behind closed doors. Hoffman, who briefed the council on his report and took questions from members, had reportedly asked for a private session so he could talk freely without legal repercussions.

During breaks, BuzzFeed News approached some of those criticized in the Hoffman report. Former APA presidents Gerald Koocher and Ron Levant have already issued a rebuttal, criticizing Hoffman's "confusion and unfounded conclusions."

Levant, a counseling psychologist at the University of Akron in Ohio, declined to add to this statement. "I'm not talking to the press," he told BuzzFeed News. "That's the decision I have made."

Larry James, of Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio, who in 2003 was the chief psychologist at Guantánamo, also rebuffed an interview request.

But the Society for Military Psychology, which James represents on the APA council, has come out strongly against the association's response to the Hoffman report. Its president, Thomas Williams of the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, has written to APA officials warning the organization against adopting a "politically motivated, anti-government and anti-military stance."

When the council meeting was finally opened up to the public, Arrigo was recognized for holding the APA accountable.

From the #TorturePsychology debacle, a hero emerges http://t.co/eezq9CSavg

"We honor you for being the finest possible role model," said Walter Hillabrandt of the District of Columbia Psychological Association, his voice cracking with emotion.

But after years of being attacked by some of the APA's leaders, Arrigo was skeptical about the organization's commitment to change.

"I'm very touched by this," she said, "but at the same time I'm very wary that this is a public relations event designed to shut me up."

Emotions continued to be laid bare as delegates reacted to the Hoffman report. "It was just devastating. It was like another Hurricane Katrina," said Darlyne Nemeth of the Louisiana Psychological Association, describing her reaction to the report's revelations.

As delegates spoke, quotations on the themes of human rights, leadership, and courage were projected onto the screens beside the podium. But the council, a sprawling body with 173 members, struggled with the magnitude of the task before it. There were chaotic scenes, as delegates debated whether or not to break out into small "open spaces" to discuss particular issues.

"We've now talked about this for 15 minutes," said a frustrated McDaniel, trying to move the discussion to a vote.

Eventually, delegates agreed to proceed as a large group and start debating specific policy changes recommended by McDaniel, Kaslow, and the rest of the APA's current board.

A big part of psychology’s problem is that it is so diverse that it sometimes seems to have multiple personalities.

Clinical psychologists work with people with mental health problems. Other specialties include educational, family, and sports psychology — which again are focused on the welfare of their clients.

But "operational" psychologists — who work with intelligence agencies and law enforcement — exist in a different world. Their main loyalties are to the organizations that employ them, not the individuals they are asked to assess.

Then there are academic psychologists of various stripes, studying myriad aspects of human behavior and thinking, from how our brains process information to our sense of morality.

So diverse is the APA, in fact, that it has 54 divisions, each of which has a say in the Council of Representatives that debated the Hoffman report today. So, too, do the state psychological associations that license professionals providing psychological services.

Those disparate voices have just two days to reach a consensus on a new course for the APA. On Friday morning the council will meet again to finalize its vote on new policies — including the proposed ban on psychologists participating in national security interrogations.

The stakes are much higher than the future of the APA, Bryant Welch, a clinical psychologist in Sausalito, California, told BuzzFeed News.

"Right now, the entire profession is being tarred with this," said Welch, who was the APA's executive director for professional practice until 1993. "It really breaks my heart."

Larry James was the chief psychologist at Guantánamo in 2003, not 2004. And Bryant Welch was the APA's executive director for professional practice until 1993, not 2002.