After every mass shooting in recent history, including the Parkland, Florida, high school shooting on Feb. 14 that left 17 dead, people start talking about “smart guns," and whether these high-tech firearms could be a solution to the United States’ gun violence epidemic.

Smart guns, whose embedded technology ensures only authorized users can fire them, have been around for nearly two decades, and a 2016 survey found that nearly 60% of Americans, if they were buying a new handgun, would be interested in a smart firearm. But due largely to political pressure from gun rights proponents and a lack of investment in their development, some of the most promising smart gun technology isn't even for sale in the US, or is still only in prototype form.

There aren’t many smart guns to choose from. Major US gun manufacturers seem wary of developing or selling smart guns, and with reason. After Colt and Smith & Wesson, two major US gun manufacturers, agreed in 2000 to create government-sponsored smart guns to prevent accidental shootings and gun deaths, a boycott from gun owners nearly drove them out of business. On March 6, Smith & Wesson told shareholders it hasn’t invested in smart gun technology and has no plans to.

Colt and Smith & Wesson did not immediately respond to request for comment.

Meanwhile, the only all-in-one smart gun system on the market is the Armatix iP1 Pistol, a semiautomatic weapon developed by a German company that’s designed to fire only when it’s within a 10-inch range of a paired RFID watch. It’s only available for purchase abroad, and it’s pricey at $1,798 ($1,399 for gun and $399 for watch) compared to similar pistols, which typically cost between $250 and $1,000. Researchers have also demonstrated that it’s possible to hack the gun.

The iGun is similar to the iP1 in that its radio technology uses a wearable — in iGun’s case, a ring — with an ultra-low-frequency chip inside. Within a quarter of a second, the gun sends a signal to the ring, verifies that it’s the correct ring, and unlocks the gun, which is then ready to fire. It was first developed nearly 20 years ago, but it’s still only in prototype form.

And the $400 Intelligun by Kodiak Industries lets you lock and unlock a gun with your fingerprint, the way you’d open an iPhone. But the add-on device has significant limitations: It has to be installed, and it works only with a Model 1911 pistol.

The opposition Colt and Smith & Wesson encountered isn’t unusual. While gun rights advocates aren’t against smart guns, per se, many fear government intervention could one day limit gun owners’ ability to buy and use traditional guns.

Dudley Brown, the president of the National Association for Gun Rights, told BuzzFeed News in an email, “As long as it’s not government-mandated, in any manner, we have no objection to new technology added into firearms. We would strenuously object to any and all efforts to require it, though.”

The National Rifle Association did not respond to multiple requests for comment, but on its website, took a similar stance: “The NRA doesn’t oppose the development of “‘smart’ guns, nor the ability of Americans to voluntarily acquire them. However, NRA opposes any law prohibiting Americans from acquiring or possessing firearms that don’t possess ‘smart’ gun technology.”

Some gun owners also worry about smart guns’ limitations. Timmy Oh, CEO of VARA, a company working on a biometric firearm safe, told BuzzFeed News he strongly supports the creation of smart guns, but said he's not yet ready to buy one himself. “Guns need to work every single time, and I’m not comfortable with putting my life dependency on [smart guns] yet,” said Oh.

Further complicating the issue is the question of smart guns’ efficacy.

With the exception of Sandy Hook, where the shooter used his mother’s guns, most existing smart guns or prototypes would not have been able to stop recent mass shootings. That’s because most shooters in recent history owned their weapons. Of the 143 guns possessed by mass shooters since 1982, 75% were obtained legally.

Determining the potential of smart guns to reduce shooting homicides is more complicated. There isn’t much public data on what percentage of guns used in firearm-related homicides in the US were legally obtained. Only a small fraction of the weapons involved in gun crimes are recovered, so in most cases, it’s difficult to determine how exactly the weapons were acquired.

However, two smaller-scale studies show that most guns used in criminal assaults were illegally obtained. A 2008 city-level study on crime in Pittsburgh revealed that most firearms used in gun crimes were not owned by the perpetrator, and a 2015 survey of inmates in Chicago found that 40% of them obtained their guns on the black market or by theft.

So while current smart gun technology would not have prevented the Parkland shooting, there’s evidence it could reduce self-inflicted and accidental gun violence and, potentially, gun-related homicides.

Margot Hirsch, president of the Smart Tech Challenges Foundation, which funds gun safety technology projects, told BuzzFeed News, “Personalized gun safety technologies will not address every facet [of gun violence], but they do offer a promising solution to prevent youth suicides and accidental injuries and deaths, the majority of which occur because a youth has used a family member’s gun.”

A 2018 study that looked at gun data from 2012 to 2014 found that 5,790 US children, on average, receive medical treatment for gun wounds every year, and about 21% of those cases are unintentional.

And smart guns could improve on existing low-tech gun safety options, including flawed trigger locks, which require a key or combination to unlock. “The problem with these [locks] is that there is a potential for firing while you’re unlocking it, and accidental triggers are common,” Oh said.

One type of smart gun that takes the issue of mass shooting head-on is called gUNarmed. It uses location tracking to prevent a firearm from being used in public places, like schools and government buildings. While nascent, the still-developing technology is one high-tech solution that could someday help prevent mass shootings.

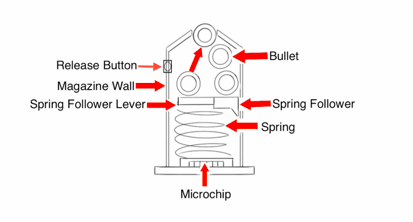

“The system I’m developing is unique. It focuses not on the person, but places,” said Chloe Green, the Northern Virginia–based, 17-year-old roboticist behind gUNarmed. The device can be retrofitted with any gun that uses magazines, like the semiautomatic AR-15 rifle used in Parkland.

The idea of a gun with location-based technology that renders it useless in a banned zone may not sit well with many gun owners who want to be able to use their firearms on-demand. Green isn’t deterred: “I want to work with gun owners to give them the choice to make America safer."

However, for gUNarmed to be truly effective, the location tracking technology would need to be accurate and unspoofable, something Green is working on, using a grant from the Smart Tech Challenges Foundation. gUNarmed would also need widespread adoption to successfully prevent mass shootings in schools, which would likely require a government mandate — something gun owners would probably oppose.

As with almost anything that could possibly change the status quo on guns in America, smart guns are highly politicized. A controversial government mandate meant to promote their development is counterintuitively one of the reasons why you can’t buy one in the US.

The New Jersey Childproof Handgun Law, passed in 2002, requires that once a smart gun is sold anywhere in the country (even outside of New Jersey), all New Jersey gun shops must, within three years, only carry smart guns.

Because the law restricts what guns people can and can’t buy, even if only in New Jersey, guns rights supporters nationwide vehemently oppose it.

The law backfired, making smart guns controversial for gun retailers thinking about selling them. In Maryland in 2014, for example, when Andy Raymond, the owner of the Engage Armament gun shop, said he’d carry the Armatix iP1 smart handgun, he received so many death threats from gun owners that he eventually backed down.

Eugene Volokh, a professor at the UCLA school of law, told BuzzFeed News the 2002 law is a significant factor influencing whether smart guns will be sold in the US. “Instead of either cheering smart guns as a new technology that helps gun owners, [gun proponents] see smart gun technology as a threat. And it’s not just a phantom threat, but a real threat. If smart guns are developed, that will lead to the gun restriction that gun rights enthusiasts worry about, at least in New Jersey and maybe elsewhere,” he said.

It also gives gun manufacturers a legal disincentive to developing smart guns, Volokh said. “If they do [make smart guns], then they’ll get huge opposition from one important part of their market — gun rights enthusiasts — that may overcome the benefit they get.”

This year, this law’s influence on smart gun availability in the US could change. On Feb. 28, in the wake of the Parkland shooting, the New Jersey state legislature debated seven new gun law bills. Among them is A1016, which, if passed, requires New Jersey gun shops to carry “at least one personalized handgun,” rather than only personalized handguns.

In a statement emailed to BuzzFeed News, current governor Phil Murphy’s press officer Dan Bryan hinted at support: “Governor Murphy supports efforts to promote smart gun technology and ensure that smart guns are an option for New Jerseyans.”

But even though the new amendment is significantly less restrictive than the 2002 bill, it’s still a mandate, and seems to already be gathering opposition from gun rights proponents. On whether he’d support the new bill, NAGR’s president said, “Absolutely not. By supporting this legislation we would be approving the very concept that the state can tell the private business what products it should offer.” The NRA did not respond to a request for comment.

Beyond this controversial law, those developing smart gun technology need additional funding to take their projects to market.

Professor Volokh believes that gun manufacturers, especially new ones that don’t have an existing customer base to alienate, have strong incentives to develop or invest in smart gun technology. “Gun manufacturers face a rare problem. ... A modern handgun will work well for many decades, and perhaps for centuries. Gun manufacturers will get no extra business from a typical satisfied customer — again, setting aside collectors and other enthusiasts,” Volokh said.

Additionally, according to Volokh, whoever patents this kind of technology “could sell billions of dollars' worth of guns in the span of only a few years, as many millions of gun owners decide to upgrade to the safer versions.”

But gun owners’ fears of government mandates on smart guns complicates such development — and until they’re assuaged, it may be a long time before someone can even buy a smart gun in the US.