1. Crime in New York City continued to fall in 2014.

Speaking at a news conference Monday, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that the city's overall crime rate fell 4.6% in 2014. This is not entirely surprising, as the city has gotten safer nearly every year since 1991.

But! Crime had actually gone up slightly in 2011 and 2012, and remained fairly stable in 2013 — so last year's decrease is good news. It brought the number of major crimes in New York to roughly 100,000, about the same level as 2010.

2. In particular, the city's murder rate fell to its lowest recorded level.

There were 332 homicides in New York in 2014, the NYPD announced. That's the lowest number since 1963, the first year for which records are available, and a huge decrease since 1990, when the city saw 2,245 homicides.

Still, the year-to-year decrease was a relatively meager 0.9%, with 2013 logging 335 homicides.

3. And most other major crimes were also down.

The number of reported rapes in New York fell 1.7% in 2014. Burglaries were down 4%, and the number of assaults dropped 0.6%.

Robberies were down a whopping 13.6% — except in the gentrifying neighborhoods of North Brooklyn, such as Greenpoint and Williamsburg, where the rate actually increased. Blame the hipsters and the bourgeois bohemians.

However, grand auto larceny — i.e. carjacking — increased by 3.6%.

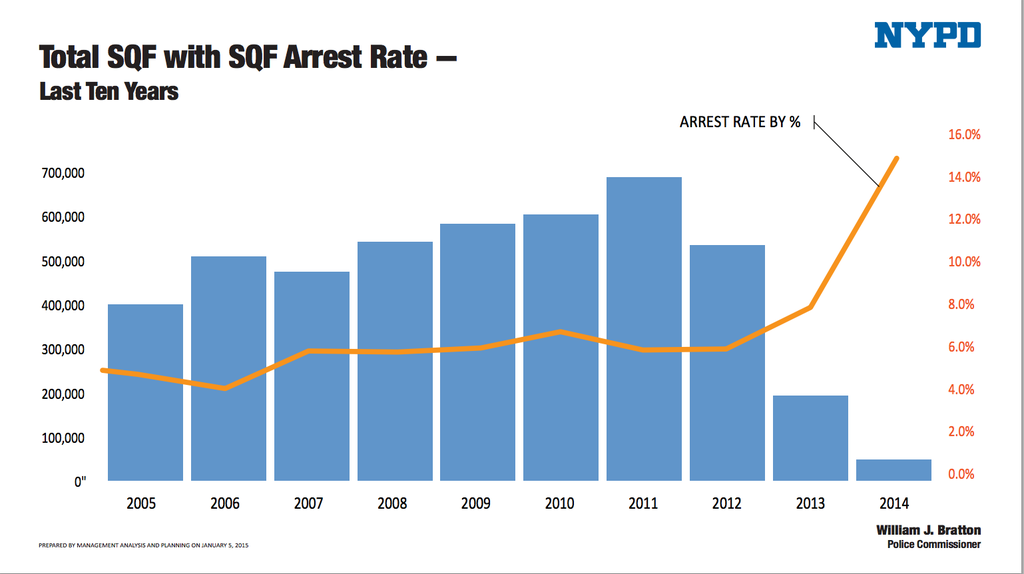

4. Stop and frisk incidents fell by 75%.

Stop and frisk is a controversial policing tactic in which cops routinely detain and question people on the mere suspicion they were involved in criminal activity — even when there isn't probable cause. It was one of the central practices of the NYPD under Police Commissioner Ray Kelly, during the administration of Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Stop and frisk drew a lot of flak from black and Latino activists, who pointed out that nearly 80% of those stopped where people of color, even though they constitute only 51% of the city's population. Moreover, just 12% of those stopped were eventually charged with a crime.

De Blasio made ending stop and frisk an important promise of his campaign and, judging from the stats he presented on Monday, has delivered. Not only are stops down, but the percentage of them that result in arrests is up dramatically.

That said, the decrease in stops may not be all that it's supposed to be. As the New York Times wrote last September, "many who live and work in [minority] neighborhoods say they see scant evidence of change, and some say the police are simply not reporting some or all of their stops."

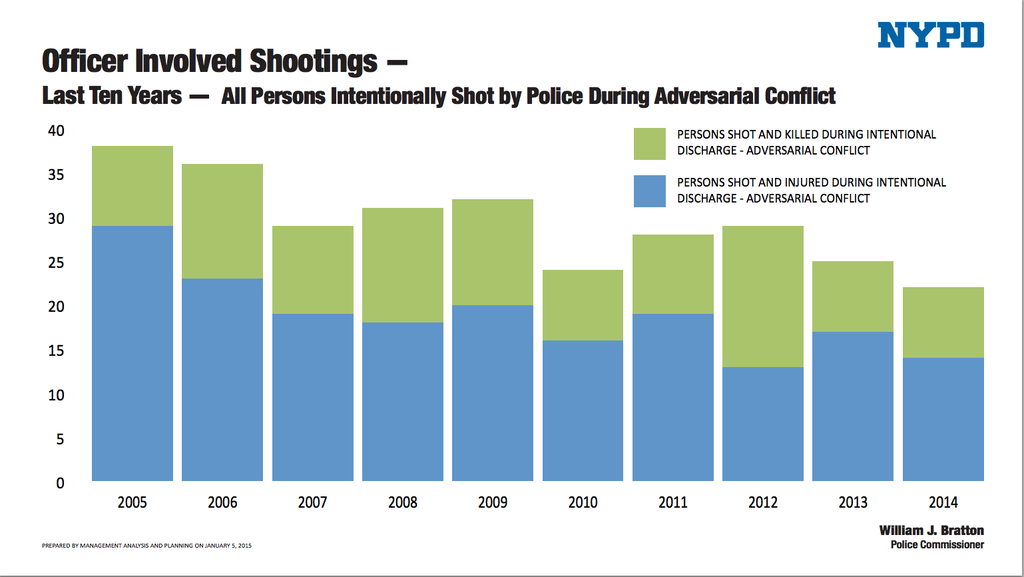

5. Police officers shot fewer people, but killed more of those they did shoot.

The number of people killed by NYPD officers fell slightly in 2014, although the number was about the same as it was in 2013. That is a marked decrease from 2012, which was the worst year of the decade in terms of cop shootings.

But, as the case of Staten Island resident Eric Garner made clear, police officers sometimes kill people without shooting them.

6. Still, a lot people are upset with what they see as discriminatory policing on the part of NYPD.

At the news conference Monday, Bratton admitted that "a significant number" of New York residents have "concerns about over-policing" and about "some of our quality of life enforcement initiatives."

That is quite an understatement. Over the past few months, tens of thousands of New Yorkers have taken to the streets to protest against the NYPD.

The trigger for those protests, it's worth remembering, was a Staten Island's decision not to indict the cop who killed Garner while arresting him on suspicion of selling loose cigarettes. Arresting people for minor crimes of that kind is the central tenant of "quality of life" policing, also known as the Broken Windows theory.

That theory holds that, if police don't go after people who commit small offenses — like breaking windows or selling "loosies" — those offenses will eventually grow into a more serious crime problem. The theory's proponents, of which Bratton is one of the more vocal ones, credit it with the dramatic reduction of New York City's crime rates since the 1990s.

But the theory's critics argue that emphasizing minor arrests disproportionately hurts lower-income and minority communities — and point to Garner's death as an example of the kind of disproportionate force that cops sometimes deploy in response to small offenses.

Still, Bratton was unequivocal.

"Sorry," he said at the news conference, "but Broken Windows is here to stay. Half the people who live in this city now were not here in 1990, and have no understanding of how bad it was."

7. The public's discontent has also been expensive for the police department.

De Blasio and Bratton said that in 2014, the NYPD spent more than $35 million in overtime for cops policing the protests demanding justice for Garner, Michael Brown, and other unarmed black men killed by police.

8. And morale among some cops is low.

In a rare moment of candor, Bratton admitted that "morale in the department, for many officers, is not where we would like it to be."

A big part of that discontent stems from the fact that two NYPD officers, Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos were killed late in December. After the killings, some cops said they felt betrayed by de Blasio, who expressed solidarity with protesters demanding justice for Garner. The head of the largest police union in the city even said the mayor had "blood on his hands."

Indeed, a quick scroll through Thee Rant, an anonymous forum where NYPD officers often share their thoughts, shows that at least some cops are truly furious with Bratton and de Blasio.

9. The behavior of some of those cops has been "disrespectful."

The cops have expressed their discontent with de Blasio — and, to a lesser extent, Bratton — by publicly turning their backs on the mayor at several public events related to the two slain officers.

Despite warnings from the commissioner and the fallen cop's family, they repeated the gesture on Sunday, during the funeral of Wenjian Liu.

The mayor condemned the gesture on Monday, even though he did not refer to it directly.

"Those individuals who took certain actions this last week, they were disrespectful to the families involved," de Blasio said. "I can't understand why anyone would do such a thing in a context like that. I also think they were disrespectful to the people of this city."

Bratton echoed the mayor.

"A funeral is not a place for that," he said. "Come demonstrate outside City Hall. Come demonstrate outside police headquarters, but don't put on your uniform and go to a funeral, and engage in a political action."

The New York Post, Reuters, The New York Times, and other outlets have all noted that the NYPD has been making far fewer arrests in the last two weeks than they did during the same period last year.

For the week starting Dec. 22, arrests in general were down 66%, according to several news outlets. Summonses for minor violations were down even more — a whopping 94%. The figures for the week starting Dec. 29 also experienced a significant change, with the number of arrests dropping 56%.

It's worth noting that several of the city's police unions are currently negotiating their contracts. Given that context, the fall in arrests has many wondering whether the NYPD is engaging in a work slowdown — a labor organizing technique in which workers put pressure on an employer by doing less of their job than usual. It's a way for employees to protest what they see as unfair conditions without declaring an all-out strike.

Bratton shied away from calling the decrease in arrests a slowdown, saying that two weeks is a very small sample size and that many factors — including a decrease in 911 calls — could have played a role.

"I've not used the term 'slowdown,' which would indicate it's an organized or even comprehensive initiative," the commissioner said. "The crime numbers are still going down, officers are still out in the field, and if in fact we feel – my team and I, after our analysis this week – that we're engaged in some type of job action, that we will deal with it very forcefully."

The fact that crime is still going down despite the fact that the NYPD is only arresting half as many people has many activists wondering whether the alleged slowdown is not the ultimate proof of what they see as the failure of Broken Windows.

11. In any case, City Hall wants to make sure everyone knows they really, really love the cops.

Throughout the news conference, the mayor seemed to be making a concerted effort to rebuild his relationship with the department, which was never particularly rosy, and which has taken a turn south in the past few months.

Nowhere was that more clear than when a reporter asked him what his message was to police officers "who are not happy with you."

"My message is: We support them, we are investing in them, we will continue to invest in them," de Blasio said. "They should be proud of the achievements of 2014."

Whether the progressive mayor who ran on a platform of reining in police excess can convince a mistrusting department to work with him in the middle of a labor dispute, after extensive anti-cop demonstrations, and in the aftermath of the killings of two police officers remains to be seen.