If you’re a kid right now, and you’re doing OK, the biggest question you have about the virus might be something like: How did it start? How does it spread? Or maybe: Why is there no medicine?

But if you’re a kid and you’re not OK — and a lot of kids aren’t — you don’t have the luxury of curiosity. Instead, you have only one question about the virus that has upended your entire life. Banner Gusler, who is 10, takes a deep breath before he says it. He screws up his face. Loudly, slowly, enunciating each word, he belts out: “WHEN. WILL. THIS. END?”

The coronavirus generation has sometimes been described as a whole, vast constellation of American children, linked by the virus and the unprecedented force it is exerting on their young lives. In some ways, that is real. Every child in America stopped attending school. Every child in America stopped playing sports, doing theater, going down the slide at the park. And summer brings with it only more uncertainty, even as some kids and families begin to cautiously leave their homes.

But the reality of the coronavirus generation is not connection — it’s the opposite.

This spring, I spoke to more than 40 children across the country, as well as dozens of parents, teachers, child psychologists and nonprofit organizations.

Many children are adapting. They’re resilient. You can tell because if you ask them what they’re worried about, they say nothing, really: They feel safe, they think their parents are too. They know where their next meal is coming from. They miss their friends, they stay away from the news, they dream about a summer that might not come.

But there are many kids who are not OK.

It’s not possible to make hard-and-fast rules about who, or why. Even under one roof, different children have had entirely separate experiences with the pandemic. For some kids, the collapse of routines has been debilitating. Social isolation has been achingly hard — even with two parents at home, with routine and school and food and shelter, they have had mood swings, anxiety. Others have struggled to cope with losses — of milestones, of opportunities, of family.

One thing is clear, though: What has not changed about childhood in the midst of coronavirus is the vast reach of racial and economic inequality.

If anything, coronavirus has lengthened those tentacles, at a time when hundreds of thousands of Americans are in the streets protesting racist social structures and police brutality. Teachers and psychologists have no doubt, they say, that most of the children who were already at an advantage will emerge from this pandemic — from their small constricted worlds, from their bubbles — with an even greater lead.

And the children who did not have those advantages, who were already struggling, will almost certainly emerge even farther behind.

While the virus takes its toll unevenly, mostly affecting low-income people and people of color, all of society’s equalizers — school, health care, sports, even public parks and playgrounds — have been at least partially stripped away. So too have external support networks, the friends and organizations and adults holding many children upright. Children’s entire lives are in their homes. And their homes are vastly, vastly different.

So it’s a bit like a game of chance, really, if you’re a child living through this — whether you’re OK or not, what this whole thing has been like for you. Except it has the most American twist: For some children, the cards are stacked heavily against them.

Structure Collapse

Banner has a sweep of auburn hair and a broad, impish smile. He used to like school, but now it can be summed up in one word: terrible.

While his mom is at work as a nursing assistant, he has to stay home with his 19-year-old brother, who is not a very good teacher. In fact, Banner doesn’t think Brother, as he calls him, is good at anything besides Fortnite, where he is past level 120, and Apex Legends.

Some days Brother goes to work at a pizza place, and then Banner is with his babysitter. She’s better at teaching, but she’s in high school, so she has her own work to do.

Banner, who has high-functioning autism, liked school because he liked his teacher, and he was in a class that worked on mindfulness and yoga techniques. His mom says he was “finally comfortable” at his school this year, finally settling into a routine. And then the Rona — that’s what Banner calls it — happened. Trying to do school online has been “traumatic for everyone involved,” his mom says.

This is where WWE comes in. Lately, WWE has become Banner’s whole life.

That was how Jennifer, Banner’s mom, knew he was having a hard time.

“When he gets really uncomfortable or stressed out, wrestling is his go-to,” Jennifer says. “By the end of March, he really started obsessing over wrestling again. And that was how we knew, okay, we’re struggling.”

Jennifer has to work four days a week. She scrambles to put together childcare. Banner’s autism makes him more reliant on routines, and that makes it hard for him when the routines simply disappear.

Banner’s structured day has been replaced, mostly, by WWE. When the pandemic first started, he built himself a space he calls his cubby: the nook under his lofted bed where he has set up a whole arena for his array of WWE action figures to fight each other in, and a screen to play WWE video games and watch WWE on YouTube. There’s a sensory light under there that admits rays of watery blue and makes soft, calming ocean sounds. This is Banner’s absolute favorite place.

Banner has been having trouble sleeping since the outbreak started, so his mom orchestrated The Renovation, which meant she moved her bed into Banner’s room, and Brother’s stuff into her old bedroom. But when he wakes up in the mornings in his bed surrounded by more than 100 stuffies, his mom’s bed is usually already empty. She has to leave early for work.

So Banner wakes Brother up, and then he goes to his cubby. He comes out for breakfast, then back into the cubby. He will come out again only for a few things: a weekly Zoom call with his school on Wednesdays, which he likes; or there’s occupational therapy with a disability nonprofit called Easterseals; or he plays Wii Fit while his brother watches, which is sort of like gym class; or pizza rolls.

“You and Brother don’t have much of a routine,” Jennifer says, sighing.

That sudden absence of routine has also upended life for Khalil Hardy, who is 8. (His first name has been changed for this story.) Khalil is usually a happy kid, the kind who likes school.

“The virus has destroyed his world,” his mom, Clarissa, says.

Khalil, who is autistic, doesn’t understand why his routine has imploded. He doesn’t understand why he has to go to school online, why he has to sit in front of a computer for 45 minutes at a time. Every morning he wants to know: Is today the day I get to go see my school? See my classmates?

Sometimes, Clarissa says, he reaches out and tries to touch his teachers through the screen.

Every morning he wants to know: Is today the day I get to go see my school?

Like many kids with disabilities, especially those in school districts that were already struggling to provide adequate services, Khalil, who lives in Washington, DC, hasn’t been getting nearly enough of the services he’s entitled to, like speech and occupational therapy. His mom had already been working with a nonprofit legal group, the Children's Law Center, to fight for the services he needed. Now technology, too, has become a huge barrier, along with the district’s already strapped resources.

With Khalil struggling, Clarissa did the only thing she could think of for her son: She went on Amazon and placed a bulk order, and then she cleared out her dining room and made it into a classroom. A place Khalil recognized — where he could feel safe.

There’s an ABC rug and a giant calendar and a desk. Khalil likes to show it off: "This is my classroom."

Like Clarissa, many parents have done what they can to replicate their children’s routines: taking walks around the block before the start of the school day, having strict schedules, creating art class and phys ed. But for those, like Banner, whose parents are essential workers — or who are out of work and overwhelmed by just trying to make ends meet — routines are not possible.

Not very long ago, Banner and his mom were lying down together, just talking, and Banner admitted that he was worried about her getting the Rona. He’d never said that to her before.

His mom, who spends all day in a hospital. As soon as she gets home, Jennifer leaves her shoes outside, and then she strips and goes straight into the shower.

All Banner wants to do when she walks in the door is give her a hug, Jennifer says. But he can’t.

Does he miss his mom when she’s gone?

“Kind of,” Banner answers.

“I wish you could see his face,” Jennifer says. “He’s looking at me and he’s got this smirk.”

“Of course I miss her!” Banner erupts.

He just wants to know when all of this will end.

“I don't want my dad to die”

Few of Dr. Luke Smith’s young patients, in the flat farmland of rural North Carolina, had things easy before the pandemic. Smith is a psychiatrist and the executive director of El Futuro, a bilingual mental health clinic. He works with the children of immigrants, migrant farmworkers and meat industry workers — most struggling with mental health issues like anxiety and depression.

In the pandemic, Smith says, there’s no rule about which of his kids are doing well and which are struggling. For some, the coronavirus epidemic has given them the first chance they’ve had in years to feel safe. They used to be afraid of their parents being deported, that every knock on the door was ICE — but now, there’s no more visitors. Now they’re “cocooned” with their family, he says, safe.

Smith has had a chance to look into his patients’ homes over video chat, and sometimes, he’s seen glimpses that give him hope and relief: a little girl who called in while her family was at the dinner table together, eating Burger King — Smith had been worried they weren’t getting enough to eat. Some kids who struggled in school because of racism or cultural barriers are doing better academically.

But other kids are much worse off: “reclused in their rooms,” he says, sleep-wake cycles reversed, their parents gone all day because they’re essential workers. Some kids worry constantly about what they will eat next. Others watch anxiously while their father leaves for work at the chicken plant, crowded in the back of a truck with other men.

Smith talks regularly to a boy who used to be doing well in school, used to turn in all his assignments. Now he doesn’t. He doesn’t have reliable Internet access in the mobile home park where he lives. He spends all day alone in his room, blinds drawn, parents at work, where he worries about them.

Before the pandemic, he’d been reticent to talk to Smith. Now he’s finally opening up, telling his doctor that he often wakes up in the middle of the night, crying.

“Since they’re gone, his parents don’t realize their kid is becoming more and more depressed.”

“Since they’re gone, his parents don’t realize their kid is becoming more and more depressed,” Smith said.

Sarah Moore is an ESL teacher in Orange County, North Carolina, and works with many of Smith’s students in a school that is split evenly between white and Latino students. Within classrooms, Moore says, there are gaping income disparities — kids who live in million-dollar homes sitting next to kids from trailer parks.

The sixth grade hosts a big call a few times a week, but almost none of Moore’s ESL students are able to dial in. Fewer than five out of 30 of them are doing any schoolwork at all right now. Many have little or no internet; students with parents who are working are watching their siblings.

“Their parents are very much struggling,” Moore said. “They value their children’s education. But they’re in survival mode.”

Evan Yerena and his mom, Claudia, work with Smith at El Futuro. Claudia and her three children are together most of the day in one room, their living room, while Claudia works as a go-between with needy families in Orange County — helping them find food and social services, texting with families who the pandemic has trapped in ever-worsening domestic violence situations.

Claudia’s 12-year-old son has been fine; her 4-year-old daughter is maybe doing better, home all day with her mom.

But Evan, 10, is having a difficult time. School is hard, he says, and he misses soccer, which he loves so much — he plays goalie, and also forward. Mostly, though, Claudia has noticed that he is torn up with anxiety about his father, who works for an air conditioning company and must leave the house every day for work.

“I’m scared,” Evan says. “Because of my dad.”

He talks to his mom about his father. He says to her, “I don’t want my dad to die.” He thinks about it a lot. It’s the thing that worries him most of all, he says. He just wants his dad to be able to stay at home.

When Evan talks about the virus, and about his dad, his voice is very soft, and you almost can’t hear him as he speaks. He has a mop of thick black hair and rectangular glasses that make him look older than he actually is.

He only wants to know this: “When is the cure?”

“I want to see her in person.”

Dottie and Nora Lea Hearn are sisters, they are 10 and 11 years old, and they do almost everything together, especially now, because they are stuck in their house.

At first when they were all cooped up, Dottie and Nora did shenanigans together. Like they would take their bikes to the gas station and get themselves Icees — blue raspberry, obviously. They did a Silly String fight, and put on roller skates, and they also saw a mushroom. That was on St. Patrick’s Day, and Dottie thought she saw gold on their lawn so she ran down the stairs, but it was just a big old mushroom. Also, Dottie cut her hair with tiny nail scissors. Her mom tried to fix it, but that only made it a little bit worse.

They don’t really do shenanigans anymore.

Nora’s voice, when she talks about it, is very sad, and she sounds like she is about to cry. This is all really hard because it’s boring, and she’s lonely, and her dad lost his job at a fine-dining restaurant, and the self-serve at the gas station closed so no more Icees. But also because just days after we talk, they will move across the country, from Napa Valley, California, to Green Bay, Wisconsin — right in the middle of quarantine.

“I won’t really get to see my friends,” Nora says. No last chances to play together. No hugs goodbye.

Even though the virus’s effects on children are wildly disparate because of race and class, there are gaps within families too — gaps that are sometimes hard to understand. Nora has a big, close-knit group of friends, her mom says, and for her, losing them has been very hard.

Dottie can see the bright side of the move to Wisconsin: “We got signed up for summer camp.”

“Yeah,” Nora says, “But it’ll probably get canceled.”

They’re going to take an airplane, Dottie says, and they’ll drive to the airport the night before, and stay at a hotel because their flight is early. The best part: “The hotel has a pool. That’ll keep us entertained.”

“If the hotel doesn’t close the pool,” Nora says.

Why don’t they do shenanigans anymore?

“I dunno, it’s just…”

It’s just, Nora can't stop thinking about her friends, and how much she misses them. “I didn’t even realize how much I needed them until I don’t get to see them,” she says. She misses talking to them, but especially their hugs: “There’s just something about their hugs.”

For Nora, the thought of losing her friends without being able to say goodbye has been consuming.

School is hard because it feels like they aren’t even learning anything — just doing things like multiplication problems. No one ever explains why things happen, you’re just supposed to do the work. And Nora doesn’t even do the work sometimes. Because it’s hard to get motivated. Because when she wakes up, all she wants to do is lie in bed.

Nora has been having a lot of bad dreams lately. She wakes up in the middle of the night and she just can’t go back to sleep.

“I had a bad dream yesterday,” Dottie interjects. “It was about someone coming out of the walls and pulling your hair.”

Yeah, but Nora has been having them every night. If she can even go back to sleep, she sleeps in. Sometimes she does a little bit of her schoolwork. “Then I just — I lie around all day,” she says. “I don’t know.”

One of the biggest divides parents have noticed within their families is between the introverts and the extroverts. Many kids who are happy being alone have been coping better. Then there are those for whom losing their social life, their friends, has been acutely devastating.

Two of Kathryn Meeker’s children are doing well in the midst of the coronavirus outbreak — better than ever, maybe. But Anna, who is 6 — Anna is just angry.

Anna is far more extroverted than her siblings. She misses her grandma and her church youth group and her teachers and friends. And missing them makes her mad.

There’s such an intensity to her rage, Meeker says: multiple tantrums in a day over little stuff, like putting the wrong kind of sugar in her oatmeal; pushing and screaming if her siblings are using the swing when she wants a turn. Meeker tries to help her understand her rage, but that’s hard, because it’s such an amorphous thing, the virus.

The kids were used to visiting their grandma at least weekly, if not more. They’ve walked over so that they can see her from across the street, because Zoom calls, at least for Anna, are such a poor substitute that they make her hysterical, furious: “I don’t want to see her on the screen,” she says, “I want to see her in person.”

Kathryn asked Anna if she wanted to talk to me about what it was like for her, but she would only yell back in Russian: Nyet, nyet.

For Nora, the thought of losing her friends without being able to say goodbye has been consuming. It’s the first thing she wants to do when this is all over: drive back to Napa and hug them.

If they had one question about the virus, Dottie would ask: “How did it start? Because I heard it was because of a bat.”

Nora wants to know: “How long before I can see my friends?”

“Now it’s a chasm”

Class is over, and there’s only a few more days until school’s out for the summer. But no one wants to leave. As their teachers say goodbye, the fourth-graders linger on the call.

“This is so sad,” one girl says.

“Well,” another chimes in, “at least it’s a school year we’ll never forget.”

“It’s like sometimes, when you have a birthday, and you think, ‘Wait a minute, I don’t remember that part.’ But now you’re like, ‘Oh yeah, you remember this,’ because it’s like, you’re stuck at home.”

“I survived COVID-19,” someone pipes in, to laughter.

Ms. Sullivan and her co-teacher start, again, to say goodbye, and in the chat window, her students respond with memes: Stewie Griffin shouting “NOOOOOO,” a man with his arms crossed and a comical frown on his face, declaring, “I DON’T WANT TO GO.”

“NUUUUUU,” one boy types.

As the rest of them say “Bye,” another writes into the chat window: “I don’t wanna die.”

This is how it has been for the past 10 weeks in Ms. Sullivan and Ms. Phoenix’s class at Watkins Elementary School, in Southeast Washington, DC. This is the only chance most students get to talk to their friends, to see their faces, and they miss each other so much. Finally, the fourth-graders start to log off, one by one, until it’s only Ms. Sullivan and Ms. Phoenix, and Ms. Sullivan’s 6-year-old daughter, who has spent the morning class sitting on her mom’s lap.

Some students talked a lot, asking detailed questions while they sat in their beds or at their kitchen tables. But with some students, Ms. Sullivan got only a few fleeting glimpses: one girl’s blurry chin, a single syllable of a boy’s voice as he tried to explain that he couldn’t turn his mute off. A single chat sent: “Good morning.”

And then there are the kids that didn’t log on: Many days, at least 20 students don’t call in. Ms. Sullivan’s mind is occupied with all of them, but the students she doesn’t see — those are the ones that consume her thoughts.

For weeks, there were students that she could not get in contact with at all. For one girl, it took nearly two months.

Ms. Sullivan had been close with the girl’s mom before the pandemic. When she finally was able to speak to her, she found out the family had been thrown into chaos: The mom was single with two kids, out of work and trying to string together gig jobs. Her days were spent working for Instacart, stretching to find child care.

There’s a huge split in Ms. Sullivan’s class, she says, when it comes to who is learning.

“Some of them are going to be fine,” she says. “Some aren’t. And of course, a lot of it falls along stereotypical race and class lines.”

There’s one boy in her class, white, upper-middle class — his parents split the day up in two, one of them constantly managing his schoolwork while the other works from home. “He basically has two full-time tutors,” Ms. Sullivan says. He was already ahead.

The girl who went MIA for seven weeks, who is black, whose family is low-income — she was already behind.

When Ms. Sullivan finally talks to parents whose children have been absent, they feel awful — they know their kids are missing something, and they’re torn up about it. But they’re drowning. Some kids go to work with their parents. Some are shuttling between three, four different houses. Some are helping with childcare.

“When we were all in the classroom together, the classroom was this leveling field, and that’s gone.”

“When we were all in the classroom together, the classroom was this leveling field, and that’s gone,” Ms. Sullivan says.

“All the discrepancies that there were before, that gap — now it’s a chasm.”

The thought of that widening chasm beats down daily on teachers, social workers, and school counselors in places where large numbers of kids are low-income. They know the research on what happens to kids during the summers, when they’re out of school: an academic slide that is far more pronounced for low-income children. But this is worse.

It’s not just that the time that children will be out of school is many months longer than during the summer. It’s worse because students and their families are suffering more acutely than they ever have. For many teachers, academics have simply fallen by the wayside in favor of far more pressing questions: Is this kid safe? Is she hungry? Does she own a book?

“Most teachers in public school, we walk around with that mental checklist: ‘When’s the last time I talked to that girl?’” Ms. Sullivan says. “And then as soon as I get off the phone: ‘Oh, there’s this kid I haven’t heard from in more than a week.’”

The pandemic has given Ms. Sullivan the kind of chance to look at her students’ home lives that she’d never had before. There were some kids, she says, whom she didn’t have on her “radar” before, but for whom a glimpse into their kitchens has left her worried. She’s watched parents being aggressive toward children, berating them while she sits there on camera. Sometimes a student will pause the call and return trying to fight back tears.

“You don’t see that at school, but now that you’re sitting in your kitchen, you get to see a lot more of it.”

But there is even more, now, that might be hidden from teachers’ eyes.

With school shut down, abuse and neglect have become far more pressing worries for those who work with children. The vast majority of calls to child abuse hotlines come from schools; many states saw a steep drop-off after the virus closed classrooms. Now, many children are not just cut off from social services — they’re stuck at home with their abusers.

In Ms. Sullivan’s class, though, there have been bright sides, too. She’s working more closely than ever with parents. She’s seen “a lot of beauty” for families in her class: chances to spend more time with each other, opportunities for parents to see their kids’ brilliance and creativity up close.

Technology, though, can get in the way. So much of Ms. Sullivan’s job now is tech support: walking fourth-graders through things like submitting documents or clicking in and out of windows. Are you muted? Can you click mute so that we can hear you?

Parents have struggled with figuring out how to use and install software, which can feel confusing and cumbersome. A few kids had no computers in their homes, and it took the city four or five weeks to issue them laptops.

So for some of her students, Ms. Sullivan had to throw tech out the window.

There’s one mom in her class who has been bringing her two kids with her to and from work, every day, and she was overwhelmed by the prospect of installing and navigating the school’s software. But when they talked, she told Ms. Sullivan she had been having her son read for 45 minutes every day and write in his reading journal.

The way Ms. Sullivan saw it, the mom was “being expected to do something impossible.” And she was doing a really good job of it.

“That’s great,” Ms. Sullivan told her. “You’re killing it.”

“I am?” she’d asked. “I really needed to hear that.”

Work, sickness, or fun?

Joe is so little, and little kids don’t usually remember much. What is there, even, to remember?

But lately that’s Joe’s favorite word: remember. Remember beaches? Remember swimming pools? Remember lunchtime? Remember playing in the backyard? Remember Legos?

"They’re memories from 10 minutes ago, but also from months ago," Joe’s mom, Nancy Waldoch, says — times when she didn’t even know he was making memories. After he remembers with her, Joe always wants to know the same thing: “We do that ’gain?”

Nancy didn’t think her boys would be affected by the coronavirus — especially not Joe, who is only 2 and a half. She didn’t think he would “get it.” But he does. When Waldoch comes back downstairs after working in her home office, Joe wants to know: “Were you at work or sickness or fun?”

Those are the categories he thinks about for adults now, Nancy says: working, playing, and dealing with the sickness — all the worrying, the preparations, the prevention.

It has startled many parents of young children, the way the virus has trickled down to toddlers and kindergartners.

It has startled many parents of young children, the way the virus has trickled down to toddlers and kindergartners. Some children have regressed: started wetting their beds, throwing tantrums, calling names, hitting siblings. Others, like Joe, have become obsessed with the virus.

Some parents choose not to tell their toddlers about what’s going on, trying to keep them cocooned in a bubble of safety. They’ve reasoned that the disruptions to routine — canceled daycare, absent friends and relatives — can be explained away without trauma. But even then, the virus has crept in.

Kids, parents say, can tell that something is wrong.

“At first, I was so not prepared for this to affect either of them,” says Betsy Portillo, whose 3-year-old son, Diego, was already used to her staying at home with her newborn on maternity leave.

But a week or two into quarantine, Diego started wetting himself, even though he’d been potty-trained for more than a year.

Diego is a social kid, and she can tell he misses his friends. He was never physical with his little brother, but now he is, violent outbursts that seem like so much energy building up in his little body and then releasing itself. He talks all the time about “the germies,” which is what his parents took to calling the virus — they had to keep him from touching the fire hydrants and mailboxes on their daily walks, to explain the yellow caution tape they passed around the playground where they used to be able to go.

Nancy’s older son, Francis, is almost 5, and she can see his behavior change too: temper tantrums and mood swings, uncontrollable sobbing for no apparent reason. “It’s almost like he lost his kindness bone for a while,” she says.

Nancy knows, now, that her sons’ struggles are partly a reflection of how she and her husband have been coping: the worries about money, the news on TV, the things they said to try to keep the boys from touching everything on their walks. But that wasn’t clear to them at first, how much the kids would absorb what they heard and saw and felt.

Things have gotten better for the boys lately, as Nancy and her husband have become more aware of how their own moods in the midst of this affect their children.

But still, sometimes, when the boys see crowds on their movies and TV shows, they worry. “Is the Sickness not there?” they want to know. “Was that before the Sickness?"

“Does she have the germies?”

Sitting alone in my apartment, I couldn’t stop talking to children over Zoom about the global pandemic.

Of all the stories I heard, I was drawn to the constellation of children who were not OK — because they were afraid, or because they were isolated, or simply, at 11 years old, because they were depressed.

Early on, I talked to a child psychologist, Dr. David Anderson, an expert at the Child Mind Institute, and I described the outbreak as a “generational trauma.” He stopped me. That’s not quite true, he said: It’s a generational stressor. It has put pressure on every family — but that pressure is so uneven.

We don’t know how this will all shake out. But we do know, Anderson said, that for some children, those extreme stressors will turn into trauma. Adults like to say, over and over again, that kids are resilient, but even if the pandemic’s effects aren’t clear to any of us yet, the effects of trauma are. Trauma etches itself into children’s brains; it stays with them for years, sometimes for the rest of their lives.

Trauma etches itself into children’s brains; it stays with them for years, sometimes for the rest of their lives.

Who will be left with the stamp of coronavirus, and who will not?

We don’t know, but we can guess.

As I called kid after kid, I could see the stark lines of race and class appearing from the very beginning. I could take guesses about how the kids who appeared on my screen would be doing, but sometimes I was wrong.

Talking to kids who were struggling was different than talking to adults. It was harder. They never, ever mentioned what the grown-ups had done to them — the politics, the missteps, the miscalculations — but you could see forces of all of it working in their lives anyway.

Which is always true, of course, but so much sharper now, like everything had been put under a microscope. It was hard not to think, frequently, how unfair it all was for them.

There was another part of why I could not stop talking to kids: I was lonely, and my own life was hard sometimes, and the children I spoke with were smart and funny and joyful. They were better than the adults. To say that is not to minimize their suffering, which was acute: It’s just true.

They showed me toys who wore masks and bandannas to go outside. They told me about their new family traditions — the games, the endlessly boring walks. They were isolated, but they tried to explain the worlds where they saw their friends now: where you could find the llamas in Fortnite, their Animal Crossing island, their favorite Roblox game. They showed me their art, the fanfiction they were writing to fill the time, so much time.

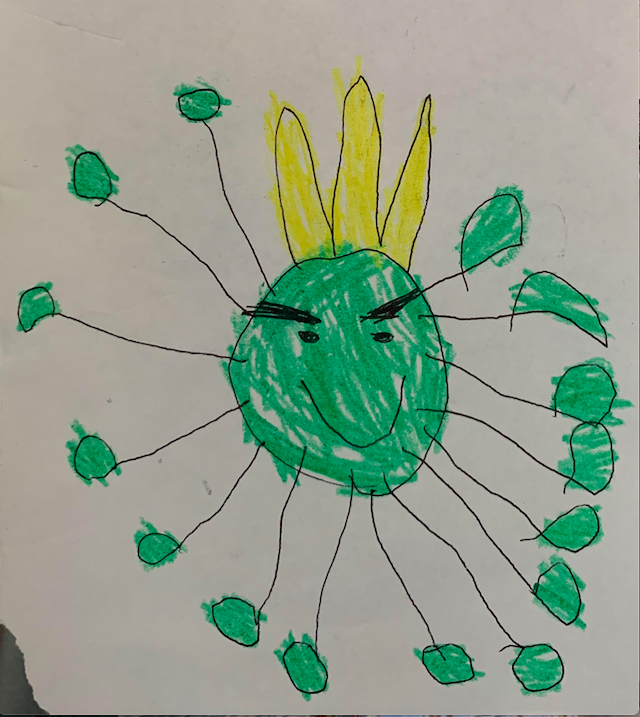

Larkin Hinkley, who is 6, showed me the most incredible drawing she made. She’s autistic, and her mind makes a lot of connections other peoples’ don’t, so when she learned about the virus’s shape and name, she drew it as a tentacled, leering green king. It’s shaped almost exactly like the scientific models of the real virus. “King Coronavirus,” she calls him.

I’m still thinking of all of them. On my own Zoom hangouts, I’ve told my grown-up friends about the funny things they’ve said — the 6-year-old boy who, asked what he most wanted to do when the pandemic was over, said, “I want to make sure the video games keep happening.” His parents hadn’t let him play before.

Mostly I am worrying about them, still, and it feels familiar, because I know it’s a tiny sliver of what their parents and teachers and counselors are feeling all the time now. I’m worrying about how long it will be before Nora gets to hug her friends, about whether Ms. Sullivan will be able to get in touch with her students tomorrow, about whether Banner can sleep at night.

I’m worrying about Diego, about the moment where he saw me on his mother’s computer screen and his eyes went wide with fear. He asked: “Does she have the germies?”

I have thought about that moment a lot. But I try to think about the next moment, too, when he asked his mom if he could go out onto their front deck and play with the bubbles.

I also think about Valentina and her mom, Francisca.

Francisca is an undocumented immigrant outside San Francisco who works as a house cleaner, which means a lot of people have stopped paying her altogether during the outbreak, when she can’t go into work. Valentina’s dad’s job has dried up too.

It’s been so hard that Valentina, who is only 9 years old, can feel it. While her mom explains how they haven't been able to get stimulus checks because they’re undocumented, Valentina pops up in the background and shouts: “WE NEED MONEY!”

Valentina gets scared when she hears about the virus, that’s true. Sometimes she feels like she’s going crazy so she runs around and hits herself and jumps up and down. But the other thing about the virus is: It means she and her mom get to spend time together.

“I love my mom,” Valentina says, and she presses herself up against Francisca’s side, very close, grinning. “She used to always go to work. She was always at work. Right away when I was sleeping she would leave, so I never got to see her.”

Now, after her schoolwork is done, Valentina and her mom watch game shows, and they draw, and they go for long walks all the way to the mountain, and it’s enough. ●