CHARLOTTESVILLE, Virginia — It was a question that Democrats had faced for years. As Beto O’Rourke traveled around the country calling for gun control, a reporter asked, how would he reassure lawful gun owners who were afraid that the government would take away their assault rifles?

“So I want to be really clear that that’s exactly what we’re going to do,” O’Rourke said, speaking to journalists under the late-August sun in a city that had been torn apart two years earlier by white supremacist violence. “Americans who own AR-15s and AK-47s will have to sell them to the government.”

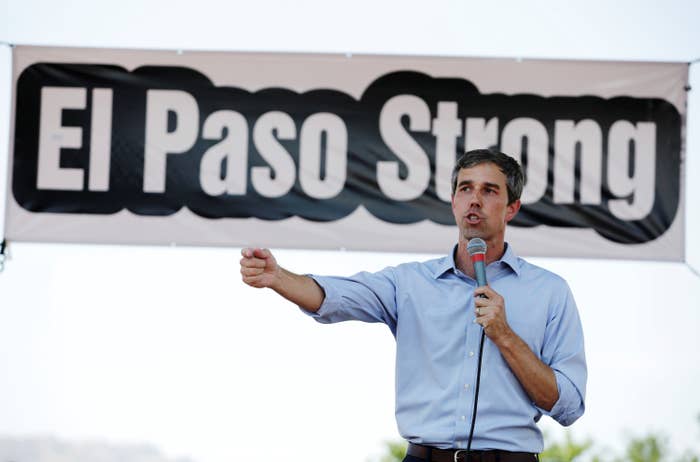

In the wake of a mass shooting targeting immigrants and Mexicans in El Paso, Texas, the city he once represented in Congress, something has changed about Beto O’Rourke the presidential candidate.

In recent weeks, he has broken through the Democratic primary’s noise with expressions of raw, visceral, and expletive-laden anger over issues like gun violence and racism. And he has taken a stance that no other major Democratic presidential candidate has touched: calling for mandatory assault weapon buybacks.

After months of campaigning without a clear, cohesive narrative or signature issues for voters to latch on to, with sometimes wobbly answers on why he is different from the 20-odd other Democrats running for president, O’Rourke has a message and an explanation for why he is the person to deliver it: What’s happening now in America is fucked up, and he has seen up close both how much that hurts and how to fix it.

In two days in Virginia this past week, O’Rourke could sometimes look like the same candidate who has struggled to win over Democratic voters. He has spent months snaking across the country speaking mostly about unity and bipartisanship, not President Donald Trump, and tacking solidly toward the middle of the Democratic field on most policies.

He also showed flashes of something different.

In a tightly choreographed trip through Virginia, O’Rourke embraced the bogeyman of the Democrat seeking to take Americans’ guns away, saying he was willing to take a politically unpopular stance he believed was the right thing. At an event the same evening, his voice rose as he spoke about the country’s “fucked up” acceptance of mass shootings, a speech that ricocheted across the internet.

But another thing was different from O’Rourke’s early presidential campaign. In both Blacksburg and in Charlottesville, O’Rourke had to take questions about why he wasn’t abandoning his presidential bid to run for a Senate seat in Texas.

It was a question no one asked him during his first trip to Iowa, in March, immediately after he began his campaign for president. But it has dogged him, to his aides’ frustration, since the El Paso shooting.

“I’m running for president,” O’Rourke insisted in Virginia.

O’Rourke began his campaign in March polling near the top of the Democratic field. But he has dropped to around 2% nationally, and his initially explosive fundraising fell off in the late spring — he raised $2.5 million more on the first day of his presidential campaign than in the entire second quarter of the year.

O’Rourke’s willingness to take on contentious national issues helped him rise to national prominence during his Senate run against Ted Cruz, particularly with a viral speech about his support for NFL players kneeling during the national anthem in protest of racial injustice, a lightning rod issue for many in Texas.

His presidential run, until recently, had been more cautious. He struggled to create any moments, like the NFL speech, that drew national attention. And especially early on, he could be indirect, even circumspect, on issues seen as politically dicey for Democrats. On his first trip to Iowa, it took three different questions about health care for O’Rourke to say explicitly that he was no longer backing Medicare for All, the single-payer health care plan crafted by Sen. Bernie Sanders that he had said he supported in 2017.

The approach clearly did not work: Other candidates, like Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Mayor Pete Buttigieg, rose in the polls — O’Rourke dropped.

In early August, a gunman targeted a Walmart in El Paso, his hometown, because of its heavy Hispanic population, echoing the anti-immigrant rhetoric of Trump along with other racist and white nationalist talking points.

O’Rourke took two weeks off the campaign trail to grieve with his city. It was there, in a parking lot on the way to his car after a speech, that O’Rourke, looking exhausted, fielded a question from a journalist about whether Trump could “make this any better.”

“He’s been calling Mexican immigrants rapists and criminals,” O’Rourke said, raising his hands in frustration. “I — I — I don’t know, like, members of the press, what the fuck?”

A staffer tried to speak, but O’Rourke cut them off. “Hold on a second,” he said sharply. “You know, it’s these questions that you know the answers to. I mean, connect the dots about what he’s been doing in this country. He’s not tolerating racism, he’s promoting racism. He’s not tolerating violence, he’s inciting violence in this country.”

The clip exploded online. It was, one person close to his campaign said, the first time since his launch four months earlier that the O’Rourke who had nearly won the Texas Senate race truly broke through in the presidential primary.

When O’Rourke returned to the trail, his campaign said it would trade some of its focus on states that voted first in the Democratic primary — skipping, for example, the Iowa State Fair, where virtually all of his Democratic challengers had just descended — in order to “take the fight to Donald Trump.” (He still recorded video messages for two big Democratic gatherings in Iowa that weekend, focused almost exclusively on gun violence.)

O’Rourke would focus on visiting places, his campaign said, where he could highlight damage he believed Trump had done. His first visit was to a town in Mississippi where hundreds of undocumented immigrants had recently been rounded up.

He also doubled down on a promise to take his campaign to some of the “reddest places” in the country, just as he had done in his Senate race. A day after he announced his support for mandatory assault weapon buybacks, he went to a gun show in Arkansas, speaking to Trump voters about gun control.

The new tact isn’t yet registering in polling: A national Quinnipiac poll last week found O’Rourke’s support at 1%, basically unchanged since earlier in the summer.

O’Rourke’s new candidacy still has much in common with what came before. His stump speeches still lean heavily on the idea of unity, and he still presents himself as a candidate who is positioned to win over moderate and conservative voters, particularly in Texas.

O’Rourke’s decision to take his campaign away from early states, too, is hardly new: Friday and Saturday marked his fourth trip to Virginia as a presidential candidate, and he visited six states in the space of his first week as a presidential candidate.

But his latest Virginia stop fit tightly into his campaign’s new narrative. He went first to Bland County, a rural area that had voted 84% for Donald Trump and where, his campaign said, no recent presidential candidate had ever visited. There, he drew a tiny crowd in a diner and convenience store that displayed Trump 2020 hats and T-shirts.

In Blacksburg, he drew hundreds of people at Virginia Tech, where 33 students were killed in a 2007 mass shooting. Some students waited in line for hours to get into the auditorium, holding cellphone cameras aloft as they saw O’Rourke through the windows walking by them, and screaming when he entered the auditorium’s lobby.

When O’Rourke told a lecture hall full of people that he had just come that morning from Bland, a woman in the audience exclaimed, “What?!”

When he was asked, as he often is, what sets him apart from the other Democrats running for president, O’Rourke gave the same answer that he had for months, including during a tepid performance in the first presidential debates. He spoke about his decision to raise his children in El Paso, a community of Latino immigrants that was also among the safest cities in the country.

But for many in the audience, O’Rourke’s answer took on new weight in the wake of the racist killings in El Paso.

“I think [Blacksburg] was very specifically chosen because of the tragedy that happened here, and I think it was very intentionally chosen to represent what happened and link it to what happened in El Paso,” said Annika Schmierer, a Virginia Tech employee.

“It was also very intentional for him to go down to Bland County, because they never get the national attention and they deserve it, because they are hurting,” Schmierer said. “It’s very intentional, and it needs to be done by every single candidate, because we deserve to be represented.”

O’Rourke’s stump speeches often elicit emotional reactions in voters, who are drawn to his personality, listening skills, and promises of unity. It was less common in the early days of the campaign for voters to pick out particular policies or issues where they thought the Texan stood out.

But in Blacksburg, one voter had no trouble picking out what she thought were O’Rourke’s “three main issues”: guns, immigration, and climate change.

Alyssa Short, a stay-at-home mom who wore a bright-red T-shirt for Moms Demand Action, a gun control group, thought O’Rourke’s call for assault weapon buybacks was a “fantastic idea — I think it’s necessary.”

But politically, she acknowledged, it would be “very risky.”

“I don’t think it’s something he should do his first year in office,” Short said. “It’s something he should work towards. And in order to do that, he’s going to need to build a lot of trust with gun owners, and there’s so many gun owners out there who want commonsense gun laws.”

Polling shows that mandatory assault weapon buybacks are among the least popular gun control measures — the only one, in a recent poll, that wasn’t supported by a majority of Americans, though Democrats favor it by wide margins.

O’Rourke tried to find something of a middle ground on assault weapons at the start of his campaign, saying only that they should not be sold. “If you own an AR-15, keep it. Continue to use it safely and responsibly,” he said in Iowa in March. “I just don't think that we need to sell any more weapons of war into this public.”

It is not yet clear what kind of impact O'Rourke's new assault weapon stance could have for him in Texas, a state with high levels of gun ownership. On the primary trail, O’Rourke pitches himself as the only Democrat who could win the state in the general election.

O’Rourke is ditching his initial caution in other ways, too. Early in his campaign, a voter in Madison, Wisconsin, asked O’Rourke if he would “promise to stop using the f-word” while campaigning, calling it “very offensive.”

“When you lost last November, you used the f-word. It made a big splash,” the voter said.

O’Rourke said he would. “Great point,” he offered. “And I don’t intend to use the f-word going forward.”

O’Rourke broke from that on Saturday in Charlottesville, as he had in the raw moment in El Paso early in August.

“We don’t yet know what the motivation is, we don’t yet know the firearms that were used or how they acquired them, but we do know this is fucked up,” he said of the shooting in Odessa, Texas. “We do know that this has to stop in this country. There is no reason we have to accept this as our fortune, as our future, as our fate, and yet functionally, right now, we have.”

The next morning, O’Rourke said the same thing on CNN. His campaign blasted out the clip with the subject line, “Beto Makes No Apologies for Speaking Bluntly About Gun Crisis.” His campaign manager tweeted the clip, adding, “GET EVERY ONE OF THOSE GODDAMN GUNS OFF OUR STREETS.” Hours later, they were selling T-shirts — their proceeds donated to gun control groups — emblazoned with, “This Is F*cked Up.”

CORRECTION

Beto O’Rourke was interrupted by a staffer in the El Paso parking lot. An earlier version of this post misstated who interrupted him.