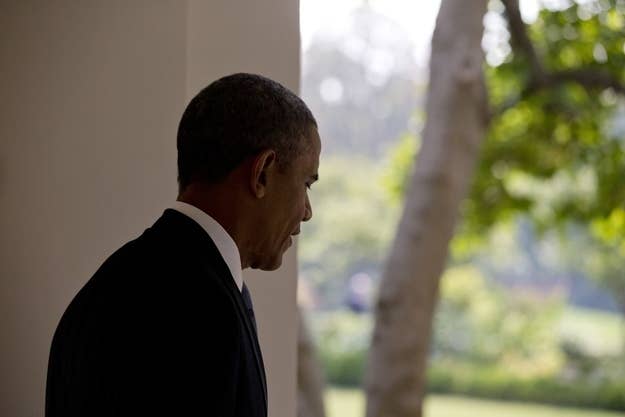

It was the speech that Obama didn't want to make, and that no one wanted to hear. For nearly 15 minutes, the president ran through the reasons for striking Syria, complete with invocations of the horrors of chemical weapons and the fact that if we let this slide, one day U.S. soldiers could face their unspeakable effects too.

It was clear and concise — and completely irrelevant.

Obama's address to the nation, which saw him standing alone taking deep breaths between phrases, came after a heady 24 hours: Secretary of State John Kerry's (planned or accidental) tip that a U.S. strike could be avoided if Syrian President Bashar al-Assad handed his chemical weapons over to international control, followed by a Russian proposal to facilitate just that, followed by Russian anger over a French-proposed U.N. resolution to table the idea because it would not rule out the use of force.

The "Russian proposal," as it's come to be known (despite signs of U.S., and possibly even Polish, involvement) gives Obama the out he would need to avoid stumbling into yet another embarrassment over his handling of Syria: the congressional vote. On Tuesday night, he said he had asked that the vote be postponed.

The Russian proposal is an out, but it's not an easy one.

Russia floated the idea, now it thinks it should set the rules. Already burned over its decision not to veto a U.N. resolution that formed a no-fly zone over Libya and provided justification for greater intervention, it will be sure to close any gaps that could allow for that. At the same time the Obama administration continues to insist that any deal must be backed up with the credible threat of force.

Then there's the small matter of moving Syria's chemical weapons – who gets to oversee that? What sort of timeframe is realistic?

There's a reason that over two and a half years, no diplomatic solution has been reached on Syria — Russia and the U.S. are fundamentally opposed in their desires. Russia, supporting Assad, does not want to see its client — its last major one in the Middle East — go and says no peace talks can be premised on his removal. The U.S. says that Assad must go and that any Geneva peace conference, originally proposed by Kerry and Lavrov in May, must be predicated on that.

"US position remains Assad leaving power as part of political process," Ben Rhodes, a deputy national security advisor, tweeted after Obama's speech. Responding to journalist Jeffrey Goldberg, he said the administration was providing "increased support for Syrian opposition" and had helped the regime become cut off from the global economy. "Geneva process to transition to new government," he wrote. But Russia does not see it that way and now, with a diplomatic win under its belt, it has no incentive to change.

Russia has not suddenly woken up with a desire to bring peace to Syria. It is brutally realist in its foreign policy and believes everything is a zero-sum game: If we win, the U.S. loses, and vice versa. It wouldn't push for a deal to rid Assad of his chemical weapons if it didn't think he could win without them.

The gloating came from all corners of Russia on Tuesday. "Obama asked Congress to put off its vote on Syria because of Russia's proposal," wrote Margarita Simonyan, the head of the Kremlin-controlled television channel Russia Today. She continued: "If the Russian proposal for Syria works, Obama, as an honest person, should give his Nobel to Putin."

Despite the back and forth of the past few days, not much has really changed.