Hollywood actor Adam Driver wasn't born when William Morgan blazed a path across Cuba with a band of guerrillas, helping Fidel Castro seize control of the country during a critical period of the revolution.

But when Morgan's widow learned last week that 36-year-old Driver was starring in a movie to be made about her late husband, the memories came flooding back from a conflict that forever changed their lives.

"This is history," said Olga Morgan Goodwin, a Cuban native who met her husband during the fighting in 1958. "He wanted the freedom for my country. He gave his life for my country."

Though movie productions have been shut down because of the coronavirus, filming for the Yankee Comandante is tentatively set for 2021, with director Jeff Nichols attached to a feature film that resurrects the life of an American who helped lead a revolution that changed the course of the Cold War.

In an exclusive interview with BuzzFeed News, 84-year-old Goodwin said she was heartened by the news last week, but admitted she has never heard of Driver, who starred in the Star Wars sequel trilogy and has twice been nominated for an Academy Award. "I don't watch a lot of TV," said Goodwin, who now lives in Ohio. "I just don't have the time."

Though two books and a PBS documentary have been created about Morgan, a former gun runner for the mob whose life changed dramatically when he arrived in Cuba, Goodwin said she hopes the movie will reveal to a larger audience a compelling figure who had once disappeared from the archives of history.

The rights to the movie by Imperative Entertainment come eight years after Focus Features optioned the story with George Clooney as the director, but never moved forward with the filming. The movie is based on an article in the New Yorker by David Grann.

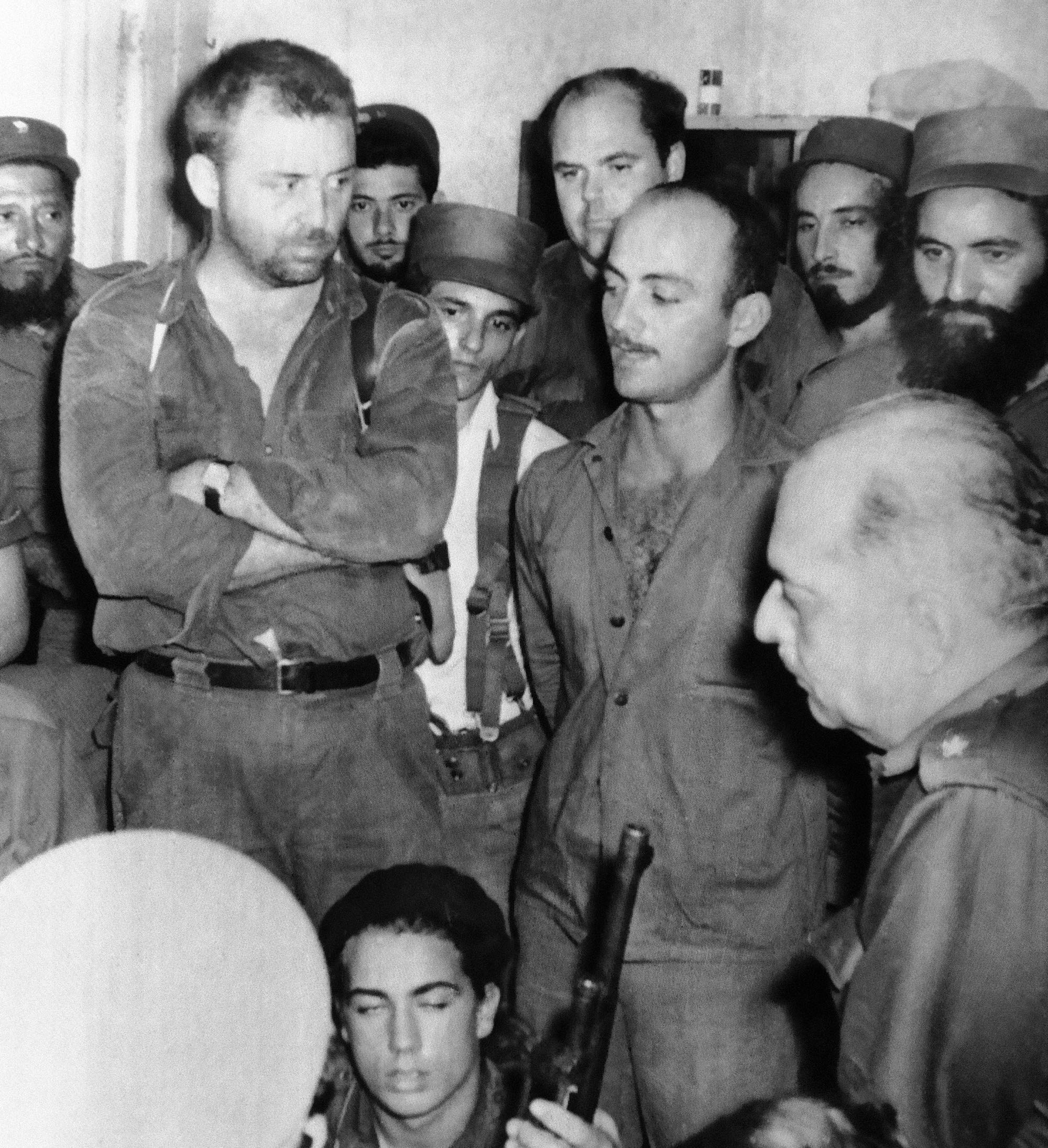

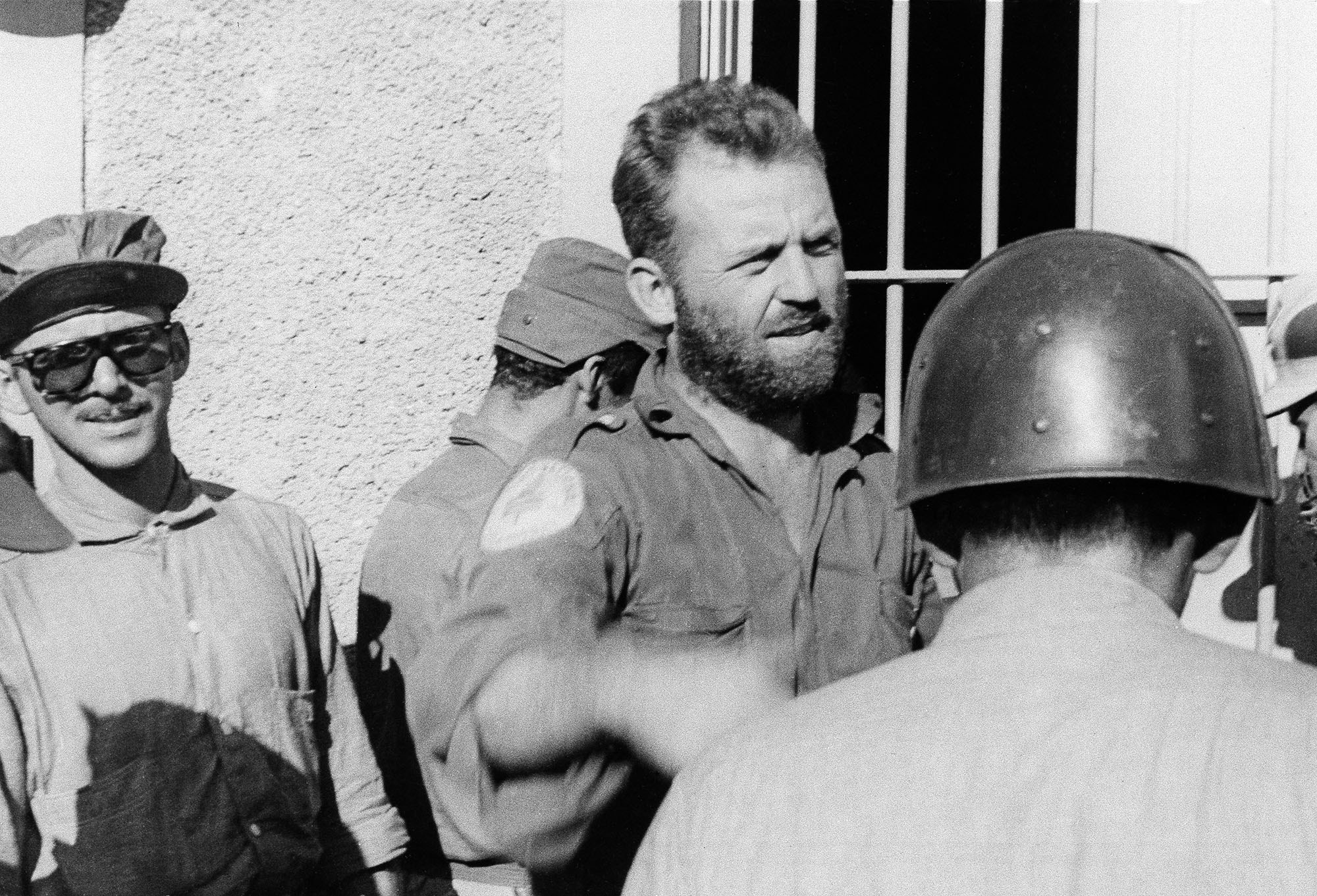

In the late 1950s, Morgan cut a swashbuckling figure who captured international attention in the media — as well as the FBI, CIA, and the Kennedy White House — after he led his rebel unit to a remarkable series of victories over the Cuban army at the height of the revolution. At the time, the guerrillas led by Fidel Castro had promised reforms and elections once they ousted the corrupt regime of Fulgencio Batista, who seized power years earlier in a coup.

A strapping figure with blonde hair and blue eyes, Morgan, the so-called Yanqui Comandante, turned up in the mountains for adventure, but quickly became serious as he witnessed atrocities carried out by government soldiers against the farmers.

A native of Ohio, Morgan was featured in the New York Times, which published a statement he wrote on behalf of his guerrilla unit that embraced the principles of democracy but criticized the United States for backing the Batista regime.

By late 1958, he and his men cleared the central mountains of soldiers so that Castro and Che Guevara, the legendary Argentine revolutionary, could sweep to victory at a time when Cuba — just 90 miles from Florida — was pivotal in the balance of power between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Though Castro promised to step down as temporary leader, he later canceled elections and forged ties with the Soviets — prompting Morgan to turn against the Cuban dictator and raise a small army to take control.

Goodwin said her husband grew angry over the executions ordered by Guevara, a key supporter of Castro, even after the enemy soldiers surrendered. "Right away, they started attacking people. No court. Nothing," she said.

After running guns to the mountains for a counterrevolution, the 32-year-old Morgan was arrested by Castro's agents, stood trial, and was ordered to be shot during a dramatic execution witnessed by an American priest.

Led to the execution wall, Morgan refused to be blindfolded and proceeded to hug the head of the firing squad before he was lined up and killed. "He died for my people," said Goodwin.

While Morgan is the focus of the movie, Goodwin's own harrowing ordeals after his death have become a part of his story.

Just days after his execution, Goodwin was captured and sent to prison, where she led women inmates in protests for better conditions. After waging hunger strikes, she was beaten and frequently thrown in solitary confinement, where she would be fed scraps of bread and rice and woken up by rats crawling over her body, she said.

In 1971, she was released after a decade, but could not return to her family home in central Cuba because the secret police would show up. So she ended up living in a convent in Havana while her parents took care of her two daughters from her marriage to Morgan.

"Olga paid the price," said Adriana Bosch, an award-winning filmmaker who produced the first documentary about Morgan, American Comandante, for PBS in 2015. "They both had that strong romantic streak. That same streak would account for their love and it's the same streak that would account for their tragedy."

Goodwin was able to escape from Cuba in a scene that rivaled some of the battles in the mountains years earlier. She hopped on one of the last boats leaving the island during the infamous Mariel boatlift in 1980, barely making it to the US shore after the Cuban navy fired shots into the hull.

Instead of settling in Miami, she moved to Toledo to be near Morgan's mother, Loretta, and later met her current husband. During those years, she became close to her mother-in-law and eventually made two promises to her that Goodwin would carry the rest of her life.

First, Goodwin pledged to restore Morgan's US citizenship, which was stripped in 1959 after he had helped Castro take power. The other promise was to bring back his remains to the US for reburial in Ohio.

Though Morgan was criticized by a senior member of Congress for helping Castro and was targeted by FBI and CIA investigations, Goodwin argued her husband fought to help free Cuba from oppression and ultimately died fighting the same enemy that threatened his native country: communism. “He loved this country,” she said.

With the help of a local lawyer, Gerardo Rollison, the State Department granted her request in 2007, but when it came to returning his body, it was a far more daunting task. Goodwin and her lawyer have written letters to presidents Bush and Obama, Pope Francis, and the Castro government, pleading for his remains.

Rep. Marcy Kaptur of Ohio met with then-president Castro in 2002 to ask for the remains. Nine members of Congress wrote a letter to then-president Raul Castro in 2009. But so far, Cuban leaders have not budged. To this day, Morgan remains buried in a remote corner of the Colon Cemetery in Havana.

Enrique Encinosa, a Cuban historian and Miami radio show host, said Morgan is revered among thousands of Cubans in the exile community of Miami because he gave his life for them. But to the Cuban government, he’s still considered an enemy. "[They] don't want to leave a place where people can put flowers for a martyr," said Encinosa.

Goodwin said she will continue to fight. The Cuban government is "waiting for me to get older and older and older," she said.

She said her late husband remained loyal to the cause of freedom in Cuba, and held no grudges against the people who put him to death. In a letter he wrote to her that was smuggled out of La Cabana prison shortly before he was executed, he said that Cuba would solve its own problems.

"I do not want blood spilled over my cause," he wrote. "Those who are putting us on trial and condemning us have their job to do, and are acting according to the conditions set out by today's politics. So if they are guilty of so many injustices, leave it to history to straighten out such faults. Revenge is not the answer. It's better that I die because I have defended lives."

Encinosa, who has written extensively about the Cuban revolution, said Morgan remains an admired figure to Cuban Americans, not just because he was a formidable leader, but because of his own personal transformation.

He said Morgan arrived in Cuba with a checkered past. He had been booted out of the US Army and had worked for the Ohio mafia. But by the time he died, he had "found himself as a human being," said Encinosa.

As he rose into leadership, he witnessed the farmers being beaten by government soldiers and discovered for the first time that he could help the Cuban people. "A guy who was a loose cannon with a criminal record," he said. "He became a hero."