BEIRUT, Lebanon — Ali Barakat is a rising star in some circles in Lebanon, as the crooning voice of Hezbollah, the paramilitary and political group that controls much of the country. He got his start singing songs about the group's fight with Israel — but it wasn't until war erupted in Syria that he caught his big break. Now his anthems about Hezbollah's battles across the border are giving him a sudden surge in fame.

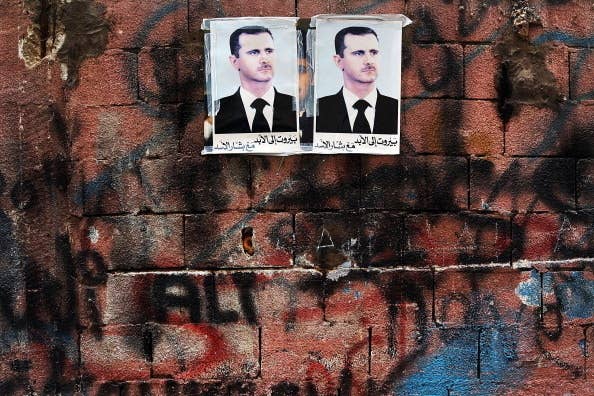

The sectarian tension fueling the Syrian conflict resonates with Hezbollah and its supporters, and Barakat taps into that. Syria's president, Bashar al-Assad, hails from an offshoot of Hezbollah's Shiite branch of Islam, and the group fears for its survival if he falls, which would empower its Sunni rivals across the border and at home. It would also sever Hezbollah's lifeline to its main backer, Iran. "If Syria went down, you and me wouldn't be sitting here talking," Barakat said on a recent evening in Beirut, puffing nargila in the Hezbollah-controlled suburb of Dahiya.

Hezbollah fighters have stepped up their involvement in Syria, and Barakat's songs have urged them on along the way. "Ya Zeinab," his best-known anthem, heavy on religious reference and Auto-Tune, called on Shiites to protect a revered Damascus shrine. Another promoted the fight in the Syrian city of Qusayr, where Hezbollah launched a major offensive this spring, seizing a key rebel stronghold. Barakat's latest effort turns the focus to a rebel-held region of Syria, pressed against Lebanon's eastern border, called Qalamoun.

Both sides paint the battle for the rugged area, home to the Qalamoun mountain range, as a potential turning point in the war. Qalamoun sits on the road from Damascus to Homs, Syria's third-largest city; controlling it would allow the Syrian regime free passage between the two cities and onward to its stronghold on the coast. The area is critical for the rebels — as a staging ground for attacks, and as a supply route to rebels elsewhere in the country. Losing it would also rob them of their last safe haven on the Lebanese border, the Sunni town of Arsal, which absorbs refugees and lets the rebels rest and resupply. One local man who aids the rebels there had a simple prediction for the repercussions if Qalamoun falls: "Disaster."

The regime has recaptured rebel-held ground across the country, notably in Damascus and Aleppo, thanks in part to Hezbollah's help. Last week, one of the rebellion's most respected commanders, Abdel Qader Saleh of Aleppo, died of wounds sustained in a regime strike, dealing the rebels yet another blow. Though momentum has changed sides throughout the grinding war, Barakat predicted that Qalamoun would be decisive. "After Qalamoun falls, we feel that the terrorism in Syria will be all over," Barakat said, referring to the rebellion. "And now our boys are ready for the fight."

As one Hezbollah fighter put it: "We think we can take over Qalamoun faster than you think."

The Qalamoun battle has been expected for months, ever since Qusayr, another Syrian city near the Lebanese border, fell in May. But while small clashes have erupted in recent weeks, it's unclear whether the major fighting will have to wait until spring, with winter rains and snow approaching. There are fresh signs, however, that an escalation is under way. Arsal has seen an unprecedented influx of refugees from Qalamoun — reportedly 10,000 since Friday — which one rebel commander from Qalamoun said resulted from sustained shelling by the regime, particularly in the town of Qarah. Some villages previously untouched by the fighting have also been attacked, added the commander, Mohamed al-Waw, who met for an interview at a local home in Arsal. "Things are escalating right now, rapidly," he said. "People are panicked in Qalamoun."

Unlike Qusayr, which sits on flat terrain, Qalamoun, with its mountainous landscape, promises a drawn-out fight. Both sides also expect it to be an especially bloody one in a war that has claimed more than 100,000 lives.

Some 40,000 rebels may be massed in the region, according to a diplomatic report from a western embassy in Beirut cited by the Christian Science Monitor last month. One Hezbollah commander had the same estimate. "They have big numbers, for sure," he said, adding that Hezbollah was "preparing something major" for Qalamoun. He expected to be deployed there within the week.

The commander, who requested anonymity because he wasn't authorized to speak to journalists, had fought in Qusayr. He said rebels there were surprisingly well-equipped, their numbers boosted by foreign jihadis: "We felt like we were fighting the whole world." He expected a similar opponent in Qalamoun, only on a greater scale — in Qusayr, the rebels eventually pulled out from the city, with many of them moving to Qalamoun.

Al-Waw, the rebel commander, said that this time around, he and his colleagues would have no choice but to fight until the end. He put the rebel numbers at 30,000, and said they were well-armed with everything from anti-tank weapons to homemade mortars, a stockpile enhanced by the recent seizure of a major arms depot in Homs. "We have nowhere else to go," al-Waw said. Losing Qalamoun "means that you can consider Homs gone, and all of the [rebel-held] villages around Damascus go down too. This is the only way for us to survive — our lifeline is in Qalamoun."

"If we're fighting the Syrian army on its own," al-Waw added, "we're not going to lose. But if Hezbollah participates full-scale? It's a possibility."

Should Qalamoun erupt, residents in Arsal — where dusty American pickups and SUVs rattle through the streets, a testament to the difficult weather and terrain — expect to suffer. Syrian refugees already have more than doubled the town's pre-war population of 40,000. Local Lebanese fighters would cross the border in one direction to assist the rebels, while casualties pour in from the other.

One local man, who used the nickname Abu Omar out of safety concerns, recalled how during the battle for Qusayr, he would drive his pickup to the border to retrieve wounded fighters. Sometimes there were so many that he'd stack them on top of one another in the bed of the truck, trailing blood along the ground as he drove back to town. "I saw some painful, painful, painful scenes," he said, speaking inside his home in Arsal.

This time around, Abu Omar said, he expected Hezbollah's foray to hit Arsal too — in fact, he saw the Lebanese town as Hezbollah's main motivation for the brewing fight. In addition to Arsal's importance to the rebellion, he said, Hezbollah also increasingly feared blowback from rebels and their Lebanese supporters over its growing role in Syria, putting Arsal, with its flow of fighters and weapons, into the crosshairs.

Car bombs rocked Dahiya, the Beirut suburb that is a Hezbollah stronghold, twice this summer, with one in August leaving more than 20 dead. In recent interviews, Hezbollah fighters blamed Arsal for the attacks, saying it harbored dangerous weapons and fighters. Fears of another were palpable when Dahiya hosted its annual commemoration of the Shiite holy day of Ashura last week, with residents worrying openly about suicide bombers and security checkpoints in endless succession.

"Hezbollah fears that any attack against them [in Lebanon] is going to come from Arsal," Abu Omar said from his living room there. Then he took out what he called his "tools": a first aid kit, a rifle, and a flak jacket stuffed with clips of ammunition. He said he'd raised a militia of 45 men to help protect the town, and that most of its residents were likewise preparing to fight. "We have no choice but to protect ourselves," he said.