BATUMI, Georgia — To viewers of Russian state television, he is a criminal mastermind from a rogue state who uses witless activists as pawns in dastardly plots against the Kremlin. To Mikheil Saakashvili, the man who was president of Georgia for nine years until Sunday, he is "our benign merchant Che Guevara," selflessly spreading Western ideas of freedom and democracy to the darkest corners of the former Soviet Union. To Russia's embattled opposition, he is a dangerous provocateur whose meddling all but unraveled their movement just at the moment when Vladimir Putin began to crack down.

Givi Targamadze, a doughy, slightly graying Georgian member of parliament who speaks Russian with a molasses-thick accent and laughs in seal-like whelps, seems an unlikely candidate for all these roles. But since he unwittingly found himself the star of a propaganda film on Russian state television a year ago, he has become a byword for Georgia's supposed pernicious schemes to undermine the Russian state.

The film, Anatomy of a Protest 2, based its allegations on grainy hidden camera footage showing a purported meeting between Targamadze and four anti-capitalist Russian activists led by Left Front leader and opposition figurehead Sergei Udaltsov. Russia's rough equivalent of the FBI, the feared and politicized Investigative Committee, accuses the activists of taking $200,000 in cash from Targamadze in order to organize terrorist attacks inside Russia. The footage was bizarre: the sound, for one, did not match the tape. The state-run channel that aired the film, NTV, claimed the recording had been given them by a random Georgian man on the street. Several independent Russian outlets conducted investigations suggesting it had been made by a special NTV department with links to the secret services.

At first, Russian opposition figures laughed off the program. Despite cries of outrage from pro-Kremlin MPs, few expected anything to come of it - as had been the case with the first Anatomy of a Protest, which accused the U.S. State Department of luring Russians to demonstrate against Putin with cookies. But authorities then launched a crackdown based on the "evidence" in the film. Three of the activists shown were arrested. One, Leonid Razvozzhayev, claims he was kidnapped while seeking asylum in Ukraine, tortured in a basement for two days, and then brought back to Moscow and forced to sign a confession, which he later retracted. Another, Konstantin Lebedev, pled guilty in April and was sentenced to two and a half years in prison.

Targamadze repeatedly denied to the Russian press that he so much as knew the activists and took the allegation in his stride, joking that he would be more than happy to meet them if the chance ever arose. The film itself was roundly denied and satirized by the Russian opposition, who called it too ridiculous to be true. Targamadze was said to have proposed blowing up the Trans-Siberian Railway. Udaltsov supposedly envisioned storming the Kremlin at the head of a red-brown brigade of leather-jacketed Communists and jackbooted neo-Nazi thugs.

Now, however, Saakashvili and senior members in his United National Movement party have admitted for the first time to BuzzFeed that the story is partly true – and that Targamadze met the activists on the former president's orders. It marks a bizarre coda to years of disastrous relations Russia's envoy to Georgia recently dubbed an "epoch of maniacal enmity." Frightened by the prospect that Georgia's pro-Western model would prove attractive enough to weaken its own autocratic "sovereign democracy," Russia portrayed the country as an ever-present bogeyman, a kind of Cuba in the Caucasus, with Saakashvili as its tub-thumping Fidel Castro. Georgia seems to have enjoyed being a propaganda villain so much that it rose to the bait and proved them right. But Targamadze's quixotic plan to support a marginal and miniscule opposition group — whether out of a genuine hope to change Russian society, a nostalgic yearning for Georgia's own revolution, or pure charlatanic adventurism — inadvertently helped discredit the wider anti-Putin movement and fuel the Kremlin's crackdown against it. And what Georgia conceived as a spur for a democratic domino effect in the region degraded to the spectacle of a few badly dressed men in a dingy apartment in Belarus concocting half-baked plans for a revolution - with no idea they were being filmed by a hidden camera.

"Givi has been doing this forever everywhere. That's his nature. I cannot stop him," Saakashvili told BuzzFeed, referring to Targamadze's line in exporting "color revolutions," over a dinner of red wine, roasted nuts and giant soup dumplings in an interview last month on a terrace in this Black Sea resort town. "I make fun of him, I call him Che Givi-ara," he added.

Targamadze still maintains that he never met the Russian activists, as the NTV film claimed, and called it a fabrication. Saakashvili told BuzzFeed, however, that he asked his old friend to meet the activists in Lithuania and then Belarus. At one point they drank 26 bottles of wine in a single evening.

Several top Saakashvili allies confirmed the former president's version of events. They denied most aspects of the film, and said the only thing Targamadze told the activists to do was a favorite part of his repertoire: smear the Russian security services' headquarters with Soviet catnip so that Moscow strays would mark it as their territory. Lebedev, the activist who took a plea bargain, made the same claim in an interview with a Russian magazine in April. Confronted with this, Targamadze continued to deny ever having met the activists, accused Lebedev of being a security services agent, and seemed incredulous that Saakashvili would say such a thing.

"I don't feel responsible for something I had nothing to do with," Targamadze told BuzzFeed as he chain-smoked Camel Lights at UNM party headquarters on George W. Bush Street in the capital, Tbilisi. "I can't vote in parliament and blow up the Trans-Siberian Railway at the same time."

The startling claim by Saakashvili appears to go some way towards justifying what many long saw as Kremlin propaganda. State media portrayed U.S. NGOs that Saakashvili worked with, especially the National Democratic Institute and International Republican Institute, as the Hezbollah of election monitoring, nefarious and tentacular spreaders of strife. Paranoid fearmongering only grew in the wake of the two countries' war over South Ossetia in 2008. Since then, Russia's anti-terrorist committee has accused Georgian secret services of working with Chechen rebels to attack the Sochi Olympics. In the wake of the Boston bombing, the slavishly pro-Putin newspaper Izvestia claimed that Tamerlan Tsarnaev had been recruited as a U.S. spy at a Jamestown Foundation indoctrination seminar run by Georgian counterintelligence in Russia's North Caucasus. When a bottle of Georgian-made Coca-Cola mysteriously appeared in Putin's residence, it was hurriedly sent off for chemical tests; his press secretary assured the nation that the president had not touched it. NTV even reused the footage originally aired in Anatomy of a Protest 2 one year later as part of another hit piece accusing the opposition of wanting to carve up Russia into several smaller independent fiefdoms. In one of the clips, Targamadze is shown encouraging Udaltsov to try and seize power in Russia's western enclave of Kaliningrad, so that Russia would have to send troops across NATO territory in the Baltics to quell it.

Targmadze was tailor-made for the role of cartoon villain. He has a reputation as something of a professional revolutionary: the NTV film introduced him as a "color revolution constructor." He was at Saakashvili's side during the Rose Revolution of 2003, led a Georgian delegation to witness Ukraine's Orange Revolution in 2004, and showed up in Kyrgyzstan in 2005 for the country's "Tulip Revolution," helping protesters in the south organize demonstrations against the president in the north. He insists the work was innocuous, limited to peaceful democratic techniques he learned from working with organizations like NDI, which helped create the anti-Shevardnadze street movement, Kmara ("Enough").

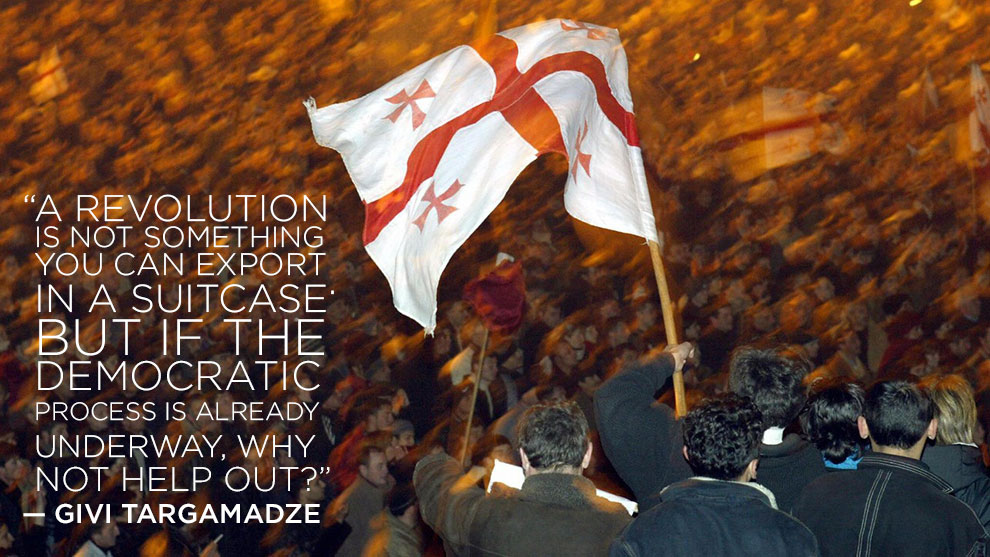

"A revolution is not something you can export in a suitcase," Targamadze said. "But if the democratic process is already underway, why not help out?"

As the color revolutions spread, so did Targamadze's notoriety. When he helped organize protests against Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko in 2006, KGB officials there accused him of planning an election-day terrorist attack to overthrow the government. Russia's Channel One ran phone taps it said caught him plotting to murder a Belarusian opposition leader. During the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election, the government accused him of bringing 400 Georgian special forces soldiers to Donetsk, pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych's heartland, under the guise of election monitors to work for his opponent, Yulia Tymoshenko. If anything, that was a step down. Local media had published phone conversations a year earlier in which Targamadze purportedly discussed bringing over members of the Georgian mafia to do the same work.

In late 2011, he turned his sights to Russia, where mass protests against Vladimir Putin's return to the Kremlin had unexpectedly broken out. Targamadze says he first reached out, through an intermediary, to the movement's de facto leader Alexey Navalny, whom he saw as a like-minded libertarian center-right democrat and who had publicly praised the Georgian model, hoping to offer advice on building an opposition movement. Targamadze says that Navalny declined, arguing that Georgians were too politically toxic to work with in the wake of the war. Navalny told BuzzFeed he never received any such offer.

Targamadze's Russia foray was the latest step in a long line of attempting to disrupt those in power. He first befriended Saakashvili in the late 1990s and quickly built a reputation as the then-aspiring leader's cartoonish wacky sidekick, using pranks and wits to outsmart their dour Soviet-style foes in former Soviet foreign minister Eduard Shevardnadze's government. He smeared Soviet statues with catnip so that Tbilisi's town strays would flock to and defile them. When Saakashvili encouraged his friend's first run for parliament, Targamadze quickly realized the government would sink to any depths to prevent him winning; he responded by running a semi-absurdist campaign that saw him take 10th graders on tours of officials' ill-gotten houses — he called it "Jurassic Park." He also erected a giant billboard counting down the days until Shevarnadze's term expired.

After Saakashvili stormed into parliament brandishing a rose and chased out Shevarnadze in late 2003, giving the revolution its name, the billboard finally came down. Targamadze was elected to parliament and chaired its defense committee, bringing in Western-style security reforms and driving Russia's military bases out of Georgia. He also negotiated prisoner exchanges during the countries' five-day war in 2008. He always remained flamboyant and loyal to his president: when a Georgian diplomat blamed Saakashvili for starting the war, he threw a pen at him and had to be held back by fellow MPs.

"People talk about all these revolutions like all I had to do was just travel around the world [to make them happen]," Targamadze said, laughing off his image. If he wrote a color revolutionary manual and published it in Russia, UNM members joke, authorities there would treat it like the Communist Manifesto during McCarthyism, an incendiary, subversive tract corrupting the population. Instead, his allies paint a picture of a romantic looking to sustain the thrill of his political youth.

"He was very important in the Rose Revolution, but he never made it into institutional politics. People had trouble switching from that revolutionary romantic angle to the normal realpolitik of the state," a senior Saakashvili aide said. "He misses that time. You always have people who don't like it, and so they continue to be revolutionaries on their own."

Whatever the scale of Targamadze's actual villainy, his alter ego in the parallel universe of Russian state media swelled to fill that role, dispatching election monitors to sow havoc across Eurasia like Fantômas' plague rats. The NTV film depicted him as directing the activists' every move by phone and Skype, even during the protests. After the film aired, prosecutors combined the case against its three activists into larger proceedings against 26 Russians charged with the violence at a demonstration on the eve of Putin's inauguration, which they said was part of Targamadze's sinister plot to spread riots across Russia. Another state TV channel showed a documentary crudely intimating that Targamadze had been recruited by the CIA in the 1990s and worked closely with the entire Russian opposition. A "former friend" of Targamadze's claimed that "if it weren't for Putin, Givi would have seized power in Russia!"

At first sight, the most confusing thing about the whole episode is what exactly the Georgians wanted with a miniscule, disorganized band of bumbling Russian Communists in the first place. Saakashvili and Targamadze grew up intoxicated on Reagan and Thatcher's rhetoric during perestroika; the Communists took perestroika as a personal tragedy and, according to footage shown in the NTV film, spent much of their time simply intoxicated.

In a previous interview, one of the activists suggested that Targamadze was drawn to them precisely because they were so impoverished and inexperienced, and thus easy to control.

"We were trying to bilk them for money so they could feel part of the greater process, which is very important for them, because that's what Targamadze lives off. That's his image - someone who can create a revolution anywhere and everywhere just by clicking his fingers," Lebedev told Kommersant Vlast magazine, hinting at Targamadze's obligations before his supposed backers. "Our difficult financial situation forces us to talk with people who'd be our enemies in another situation. But they became our tactical allies."

Targamadze admitted being in Minsk that summer, but insists it was part of an effort to prevent Lukashenko from recognizing Abkhazia and South Ossetia, two breakaway territories Georgia lost after the war. (Notably, he was still somehow able to return to Belarus after the head of the KGB went on national television to accuse him of planning a terrorist attack.) It remains unclear where exactly the money came from, if it ever existed. Saakashvili admitted paying for Targamadze's trip, but said that the Georgian government "never had the funds for this kind of things — we're not some kind of Russian oligarchs.

"He could have got it from some Russians, but we never had funds for that. We weren't really behind it," he added. "It wasn't that the Georgian government was doing these kind of things," he said, stressing that Targamadze was given enough money to travel but otherwise left to act on his own.

Regardless of whether or not any money really did change hands, Lebedev's guilty plea means the accusation that it did is treated as fact. Under Russian law, the validity of evidence agreed upon in plea bargains is incontrovertible. This means that prosecutors can use the money Targamadze allegedly gave Udaltsov as evidence without ever having had to prove its existence. (Prosecutors frequently use the tactic in politically charged cases. Navalny, the opposition leader, was convicted of embezzlement in July in large part on plea bargain evidence, even though no prosecution testimony actually indicated his guilt. His five-year sentence was later commuted.)

Razvozzhayev has been in jail for over a year now. In winter, he was extradited to deep Siberia on charges of stealing 500 fur hats in 1997, though the statute of limitations had expired. (He has since been returned to Moscow.) Udaltsov is under indefinite house arrest. They and the activists they are accused of goading into violence at Targamadze's orders face a maximum of ten years in prison.

UNM lost power a year ago to a coalition formed for the sole purpose of ousting Saakashvili. The new government vowed to investigate Targamadze over the NTV film shortly afterwards, though nothing has come of it. (Its thunder was stolen by the investigation of a firefight in Lopota Gorge which, according to the new government, involved Chechen militants recruited by the Saakashvili government to wage a terrorist campaign in Russia.) Targmadaze did, however have to spend three months in Lithuania after Russia filed an Interpol warrant on the Udaltsov case in February — the first time, he says, a country has ever tried to extradite a sitting foreign lawmaker through the agency — before the agency said the charges were politically motivated.

The luster of Saakashvii's model has been sorely tarnished. He left office on Sunday with an approval rating in the teens and Georgians furious over his anti-democratic bent. Demand for its export has, likewise, decreased. Yanukovych, the Ukrainian president, nixed an agreement with the European Union on Thursday in favor of a deal with the Kremlin that would reinforce his political power and allow him to keep Tymoshenko, his rival, in jail. Armenia has already done the same. Saakashvili's ostensibly pro-Russian nemesis, Bidzina Ivanishvili, says he is intent on moving Georgia out of Russia's orbit and closer to the EU, but has stoked fears that he will do the same by openly musing about jailing the former president. Against all that, Targamadze's traveling democracy salesman shtick seems pretty pointless.

"I don't believe that you can overturn Russia with Givi's efforts," Saakashvili said. "I wouldn't have minded if Russia had had a democratic revolution, I just don't think we would have done it.

"But Givi would go for this kind of thing easily," he added. "Even if we had told him not to do it, he would have done it anyway."