There's been no bigger headache for bank executives, compliance officials, and lawyers than instant messaging — and no bigger goldmine for regulators and prosecutors. Small wonder then that many banks now want to get rid of the messaging.

The Wall Street Journal reported Sunday that several banks, including JPMorgan Chase, the largest by assets in the United States, were considering curtailing employee access to chat rooms with traders and dealers from other banks.

These chatrooms are operated through the Bloomberg terminals that nearly every trader anywhere on earth uses for arranging trades on stocks, bonds, currencies, and commodities outside an exchange.

"Bloomberg messaging is used tremendously for trading. It's very, very entrenched in over the counter markets," says Kevin McPartland, head of market structure research at Greenwich Associates. Bloomberg says that its 315,000 subscribers send 200 million messages through their terminals every day and 15 million chats.

The problem is that, for some traders, the chatrooms turned from a convenience to a venue for market manipulation, collusion, and at the very least, embarrassment for their firms.

The LIBOR scandal, where several banks' traders colluded to manipulate a key benchmark interest rate that helps determine the price of several hundred trillion dollars worth of financial products, was largely conducted through instant messages, either within a single trading desk or between traders. Barclays and UBS have already paid more than $2.5 billion fines connected to LIBOR manipulation and several other banks are under investigation by bank regulators in different countries.

LIBOR is supposed to reflect the cost of lending between banks and is constructed by banks' own submissions of what they think that rate would be, making it susceptible to bids that would benefit traders' own positions.

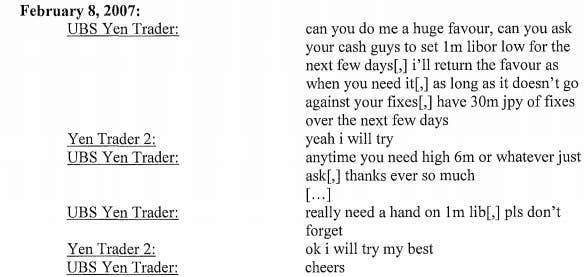

RBS, a British bank majority owned by the U.K. government, paid over $600 million to settle LIBOR claims and, in documents released by the Commodities Futures Trading Commissions, demonstrated how chats between traders at different banks could be become the stage for illegal activity.

A UBS trader asks an RBS trader to pass on a request for lower libor submissions to benefit his own trades.

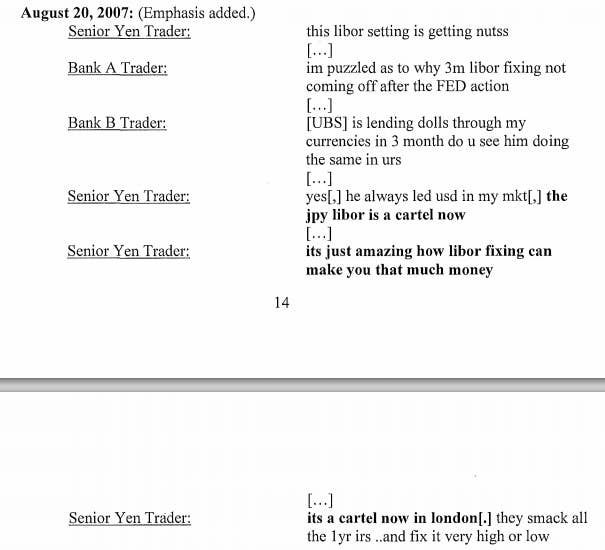

While chatting, several traders actually describe the LIBOR fixing and trading as a "cartel."

In an investigation largely by European regulators of manipulation of prices that help determine how currency trades price, investigators have reportedly focused on interbank chatrooms with names like "The Cartel" and "The Bandit Room," where, The Wall Street Journal reports "People familiar with the chat transcripts said they contained repeated references to drug use and sexual acts," as well as possible collusion. Several banks have already suspended currency traders connected with the investigation.

It's this combination of collusion and embarrassment that have driven banks to reconsider chatrooms for traders. While older ways of communicating like phone and email can still leave plenty of fodder for investigators — the failed futures brokerage MF Global left behind a trail of suspicious recorded phone calls) — they might not encourage the type of familiarity that lets traders feel comfortable breaking the law or just being crude.

"If you make it a little too easy, you get to know your competitors, your clients, you get to know each other and get a lot more casual in the conversation, it's so easy to do that in such an open forum. You don't think too hard about what you're saying." said McPartland.

Although forcing traders to go back to using the phone and email to communicate would be an inconvenience, the more time and consideration required to dial a number or just hit send could put enough sand in the gears to make repeated market manipulation more of a hassle.

"There's something about hitting that send key versus being in a chat," a former Credit Suisse derivatives trader told BuzzFeed, "and most of the conversation is vulgar and awful"

The near-universal adoption of instant messaging and groupchats for traders through Bloomberg terminals is a relatively recent innovation, only in the last five or six years has it become widespread. In the early 2000s, Merrill Lynch was famous for its in-house use of AOL instant messenger.

But the advent of universal instant messaging through Bloomberg, which usually passes through most banks' strict compliance departments unlike most standard chat services, has seemingly overridden the training traders receive about their written communications. "From day one, this mantra is beaten into you in any training program: don't put anything in writing you wouldn't want on the front page of The New York Times," said the former Credit Suisse derivatives trader.