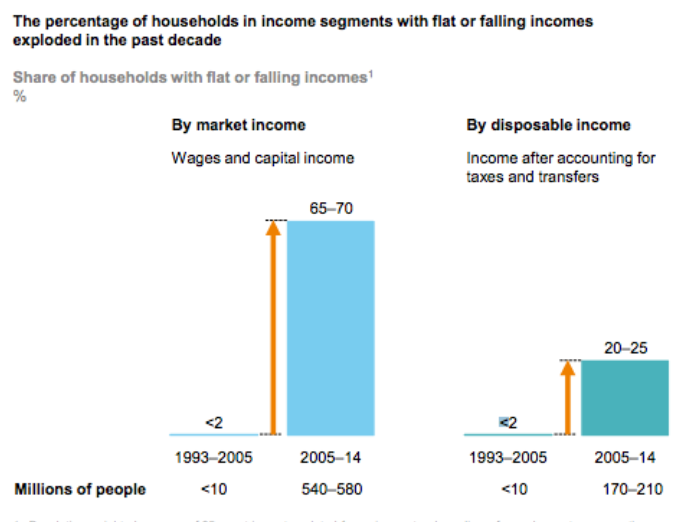

People in huge swathes of the industrialized world are seeing little to no increases in their income, a new study shows, with 65-70% of households in a selection of 25 advanced economies earning the same — or less — in 2014 as they did in 2005.

The study, by the McKinsey Global Institute, looked at 25 advanced economies, and paid particularly close attention to six rich countries: the U.S., U.K., France, Italy, Sweden, and the Netherlands. The research painted a grim picture of economic life for American households — 81% had falling "real market income," meaning money from wages and returns on investments, between 2005 and 2014.

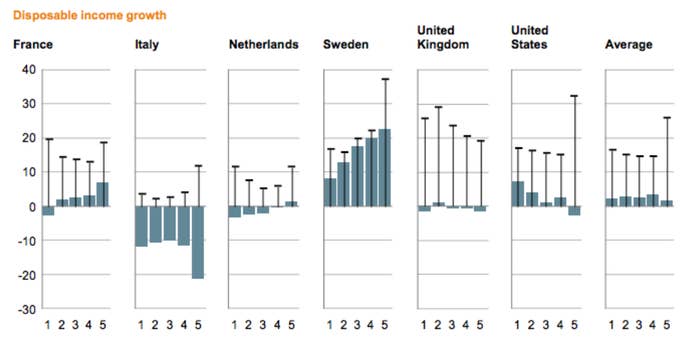

The only bright spot for the majority of households in developed economies has been money being handed out by their governments — the only way total incomes grew for most households covered by the study. Even with that taken into account "disposable incomes were nonetheless flat or down in 20 to 25 percent of income segments on average," the McKinsey researchers said.

In Italy, which had an especially deep recession followed by a weak recovery, real market incomes were flat or falling for virtually the entire population. In Sweden, on the other hand, "only 20 percent of the population had flat or falling market incomes," while in France and the U.S. households in the middle of the income distribution had "slightly" rising overall incomes thanks to increased government payments.

The data shows the success of government programs in transferring money to people with low incomes — in the U.S., tax credits that were part of the post-crisis stimulus bill played a significant role. But it also indicates that the burden of rising incomes may rest on the shoulders of tax and transfer policies for decades to come.

This chart shows growth in disposable income — market incomes with taxes and government transfers added in — broken down by income segments, with 1 being the lowest-earning 20% and 5 being the richest. The thick bars are for 2005-2014, the thin lines are for 1993 to 2005.

The McKinsey study considered "the proportion of households or people in income segments whose real market incomes were flat or below where they had been almost a decade previously," in part because McKinsey's consumer research has shown many people do not object to income inequality as long as a broad swathe of the population is still getting ahead economically.

"When there's inequality of advancement rather than inequality of income there are risks of tensions in society," Richard Dobbs, a McKinsey partner and one of the report's lead authors, told BuzzFeed News. "And when we play the picture going forward it's not something that will automatically fix itself without some help."

There's also the relative novelty of the phenomenon: What is new is seeing such a large proportion of households—"nearly two-thirds of all income groups in 25 countries...not advance economically over a decade," the study says. Between 1993 and 2005, less than 2% of households were in segments of the population whose market incomes were either flat or falling.

It's a big change after the previous decade, from the mid-90s to the mid-2000s, when real incomes - not including government transfers, increased across almost every income group in the six rich countries McKinsey studied. One obvious culprit is the financial crisis and recession that followed — the worst since the Great Depression — which was "a fundamental cause of the lack of income advancement for a large majority of income segments since 2005," the authors said.

The McKinsey researchers also blamed a number of big-picture trends that may not necessarily get better as economies grow faster. Aging populations mean more people are leaving the workforce, especially in Europe; wage earners are getting a lower of share of economic growth compared to the people who own businesses and assets; and lower-income earners now work on less-favorable contracts, which get them fewer hours of work.

"Young, less-educated workers were hardest hit," the study said, looking specifically at France, Italy and the U.S. For example, American workers under 30 in the lower third of educational attainment saw their wages drop on average by 15% between 2002 and 2012 — more than twice the wage income drop for the highest educated workers.

Another group hit hard in the U.S. were single mothers. "There are 20 times as many single mothers in the lowest income decile as in the highest," the study said, and the decline in their incomes has been faster than other households.

Many people are losing hope, and that is contribution to changes in the political environment. Almost 70% of the respondents of a survey of American, French, and UK residents who felt they were "not advancing economically and not hopeful about the future" said that "cheaper foreign labor is creating unfair competition to domestic businesses." 36% said "legal immigrants are ruining the culture and cohesiveness in our society."

But young people, despite getting hit hard by the Great Recession, are more optimistic about the future. More than a third agreed that they "expect to advance significantly in the next five years," while only 11% over 35 agreed with that. That's despite the researchers' conclusion that merely returning to faster economic growth (if that's even possible) won't save the middle class from stagnant or falling incomes.

"Part of that is maybe youthful optimism," Anu Madgavkar, a partner at the McKinsey Global Institute and one of the report's lead authors, told BuzzFeed News. "Or maybe for them, this is the normal they’re growing up in, and they're not comparing themselves to memories of what it was like earlier."