Is that a pyramid on the horizon? Or is it merely a large, pyramid-shaped pile of stone blocks? It's all about perspective, as two recent federal investigations into suspicious marketing schemes have shown.

Last year, the Federal Trade Commission went after a maker of nutritional drinks. The company told would-be customers they could get rich by selling its products — all they had to do was recruit a network of people to buy the health drinks from them. Those recruits would recruit more people into their own networks and resell the goods, which would eventually be sold on to real consumers. The whole scheme would create a lucrative web of payments that could replace a full time job, the company claimed. The structure of that payment network was distinctly pyramid-shaped.

"Rather than focusing on selling products," the FTC said, the company "uses false promises of high income potential to convince consumers to pay money to join their organization."

The FTC prosecuted the drink seller as an "alleged pyramid scheme," citing the claims it made: that its sellers, which it called affiliates, "can earn substantial income by enrolling others" in the scheme. The focus was not on finding end consumers to actually buy the products, but on recruiting new layers of people who pay commissions upward and recruit more people beneath them.

The company, the Federal Trade Commission said when announcing an injunction to halt the scheme, "focuses on recruitment rather than retail sales of its products to generate this income," and while some people at the top were getting rich, "the vast majority of participants make no money, and most of them lose money."

The company, which earned over $200 million a year from the scheme, is currently defending itself in court. Its name is Vemma Nutrition.

Today, the Federal Trade Commission made another announcement regarding a large multilevel marketing scheme involving nutritional products, with over 500,000 distributors operating in the U.S. alone. Its distributors primarily made their money not from selling the supplements and drinks to consumers, but by recruiting new distributors.

The company, the FTC said, "deceived consumers into believing they could earn substantial money selling diet, nutritional supplement, and personal care products." It told potential distributors in brochures that they could "quit their jobs, earn thousands of dollars a month, make a career-level income, or even get rich."

"In truth, the only way to achieve wealth," the FTC said in its complaint, "is to recruit other Distributors." The vast majority of distributors made little or no money, and signing up to the scheme caused them "substantial economic injury," the FTC said.

So the FTC took it to court, alleging it was an illegal pyramid scheme.

Except, it did not do that.

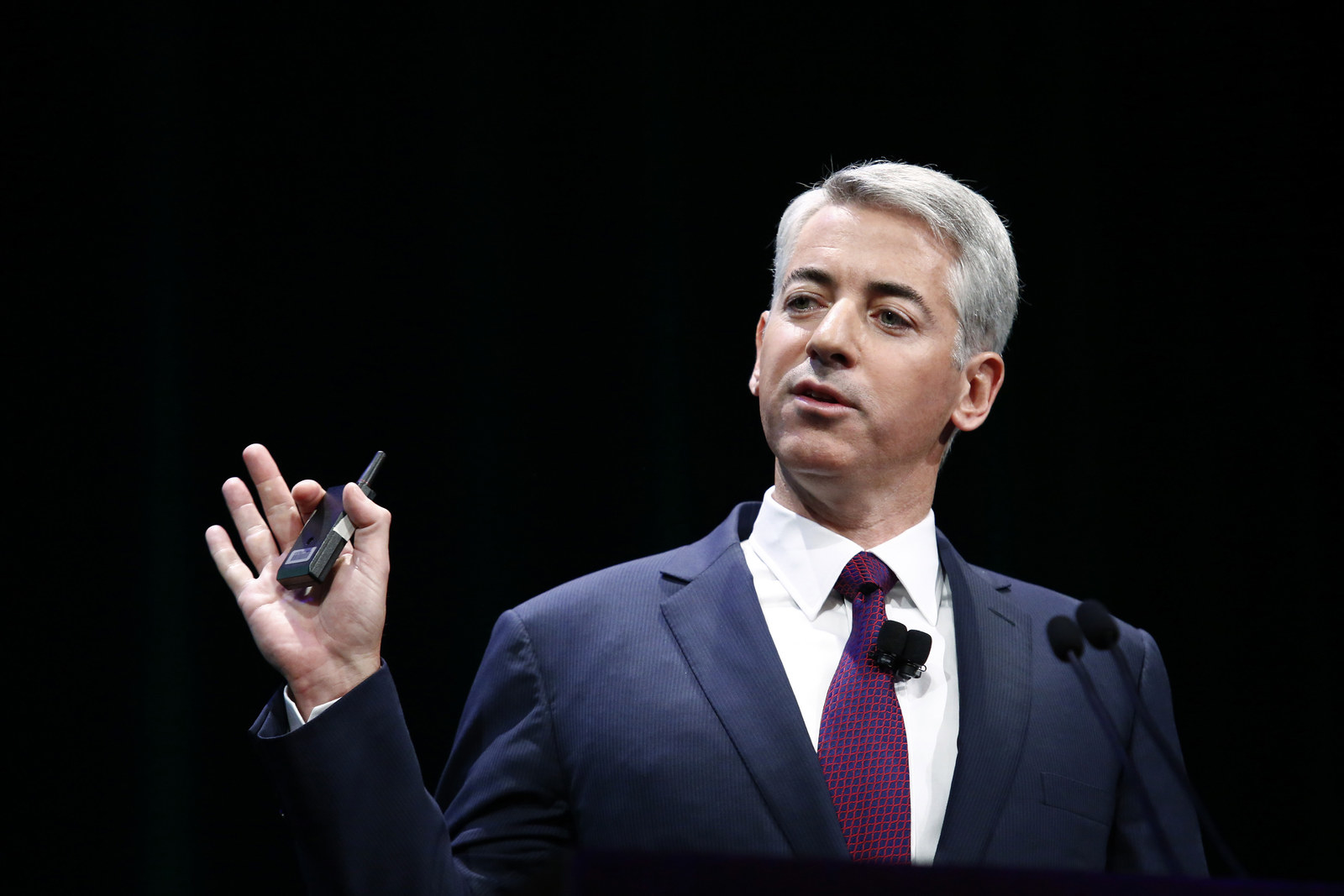

Instead, the regulator reached a settlement with Herbalife, the publicly listed nutritional products company, which is currently valued at $6 billion. For years, billionaire investor Bill Ackman has campaigned against Herbalife, betting against its stock and arguing it is a pyramid scheme that will eventually collapse — either because the authorities will shut it down, or because it will run out of new sellers to recruit.

The shutdown option looks less likely after today's settlement. When asked by reporters whether or not Herbalife was a pyramid scheme, FTC chair Edith Ramirez carefully hedged her words, saying "the focus was less on the label but rather making sure the complaint adequately alleged what we are concerned about."

Ramirez said that the goal of the complaint was to put out what it believed were "unfair and deceptive practices" on the part of Herbalife and to "obtain relief promptly and in a timely fashion, as opposed to litigating for perhaps years."

When asked again about the similarities between Herbalife and past companies that had been prosecuted as pyramid schemes, Ramirez woudn't say whether or not Herbalife was a pyramid scheme. "I will leave to you to draw that conclusion," she said.

Herbalife will not face a court trial, but the FTC's settlement requires it to restructure its business and monitor what portion of its products are actually sold to consumers, as opposed to those that are moved around among layers of distributors. The company will also pay $200 million as compensation to distributors harmed by its business.

Herbalife will have to "revamp its compensation system so that it rewards retail sales to customers and eliminates the incentives in its current system that reward distributors primarily for recruiting," the FTC said. Overall, "at least 80 percent of Herbalife’s product sales must be comprised of sales to legitimate end-users," the regulator said.

Herbalife was less circumspect than Ramirez in giving itself a clean bill of health. "The settlements are an acknowledgment that our business model is sound and underscore our confidence in our ability to move forward successfully, otherwise we would not have agreed to the terms," Herbalife's chief executive officer Michael Johnson said in a statement.

The company said that it felt that many of the FTC's claims were "incorrect," but that the settlement was "in its best interest because the financial cost and distraction of protracted litigation would have been significant." The company said that the settlement only affects its U.S. sales which are about a fifth of its total business.

Herbalife and its shareholders can now breathe a sigh of relief. The company's stock rose over 11% on Friday, and is sitting at its highest level since early 2014.

In late 2012, Ackman gave a three hour long presentation in New York where he alleged that Herbalife was a pyramid scheme and that the shares would fall to zero. He has said he would pursue his bet against the company "to the end of the earth.” Since then, Ackman has led a full scale media campaign against the company, including collecting dossiers on top Herbalife distributors.

Pershing Square did not immediately respond to a request for comment.