The Department of Homeland Security has received 1,889,311 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals applications since the program began in 2012. Its applicants are undocumented youth, brought here as children, who hope to stay in the US despite not having legal papers.

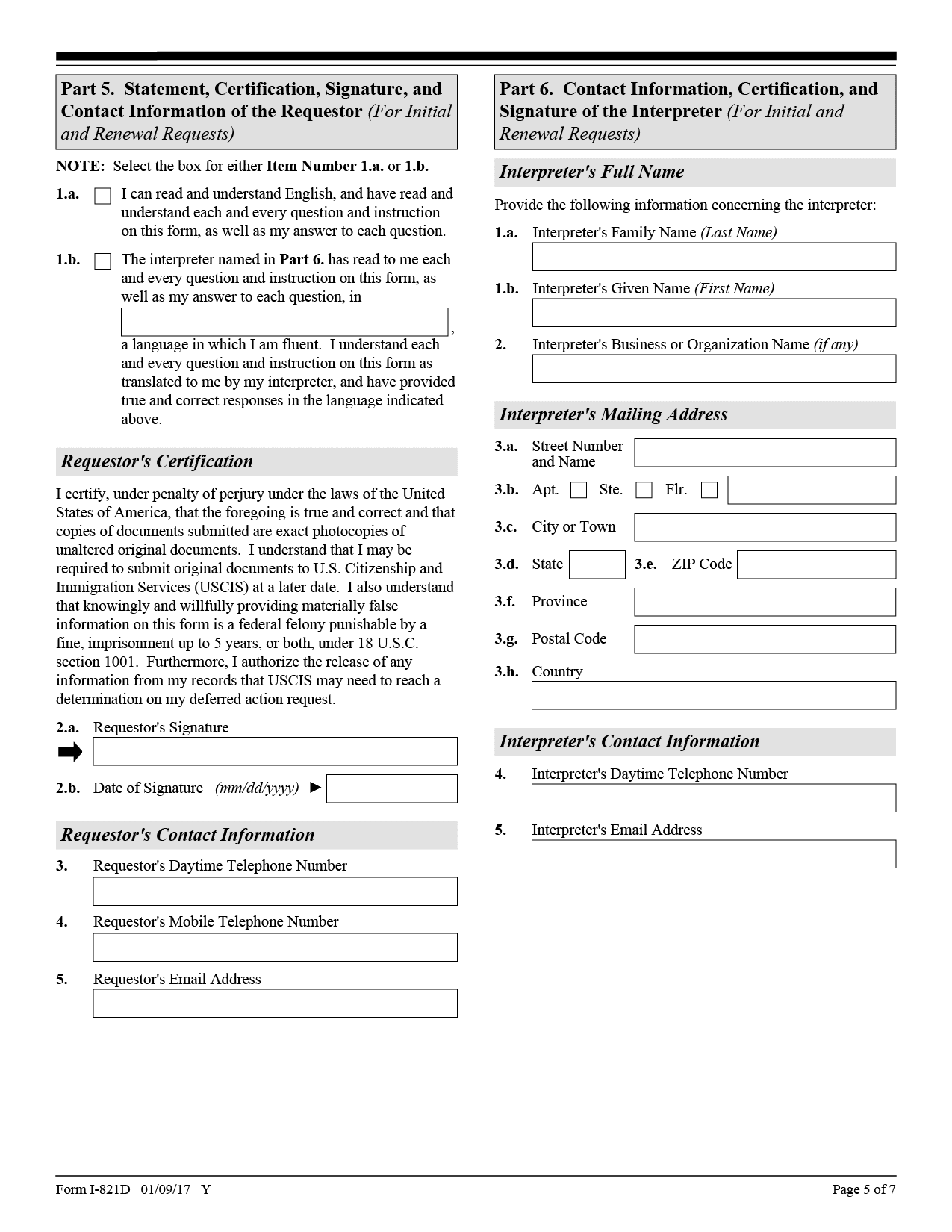

The Trump administration announced Tuesday that it will rescind the Obama-era program, inciting fear in DACA applicants and recipients that the voluminous personal information they submitted could be weaponized against them and lead to their deportation — something they were promised would not happen.

Homeland Security officials said they won’t share this information with Customs and Border Protection or US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. But advocates worry that this promise will be broken, given the Trump administration’s anti-immigration rhetoric and policies.

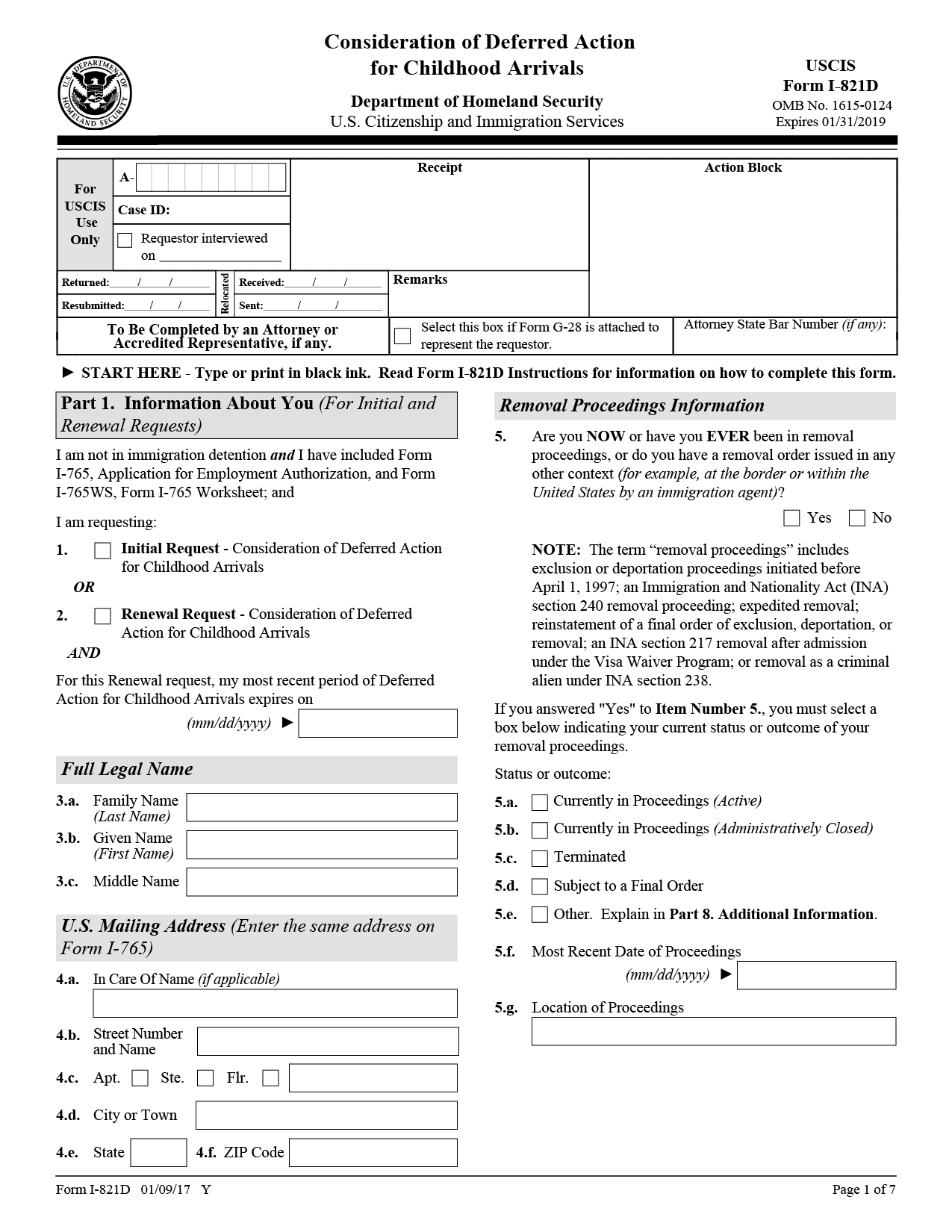

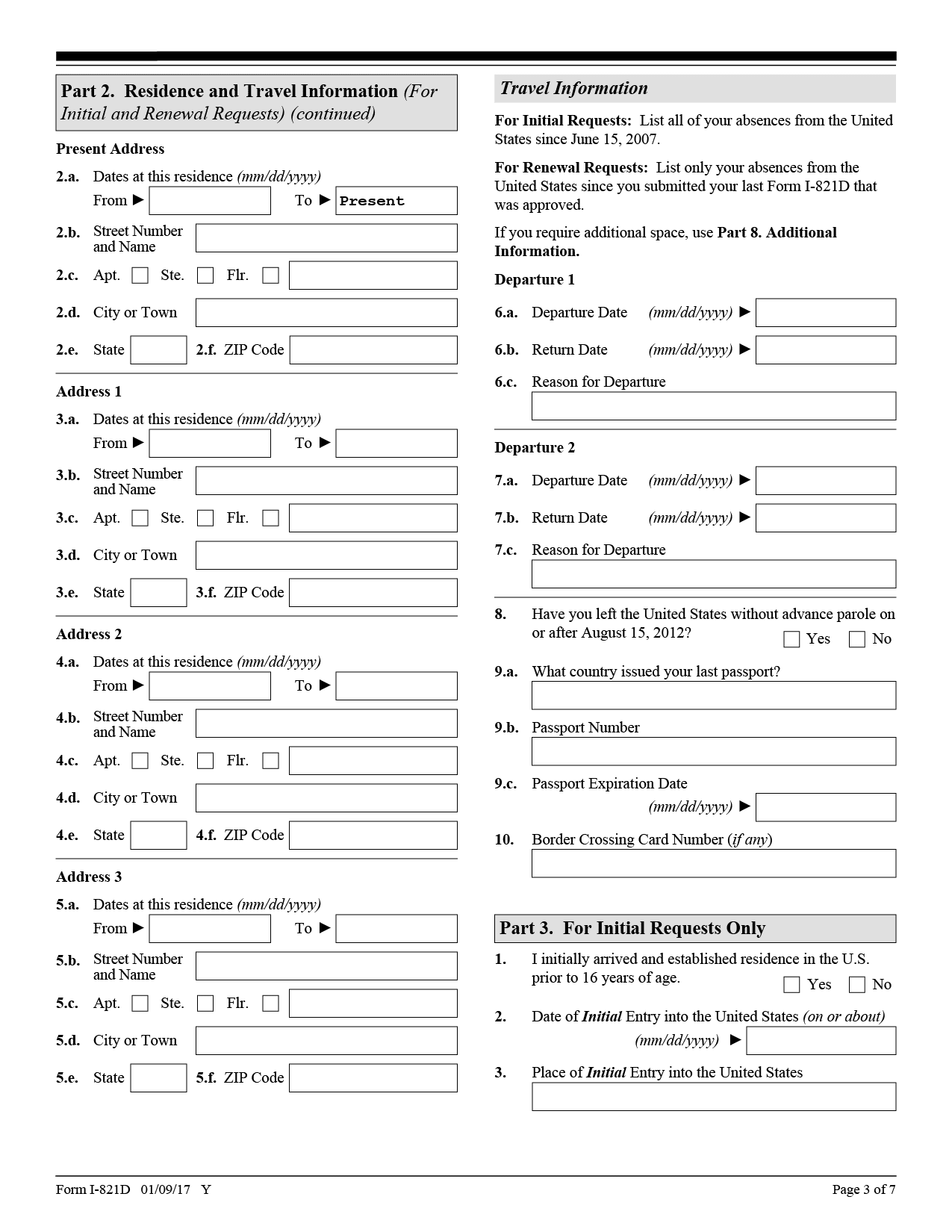

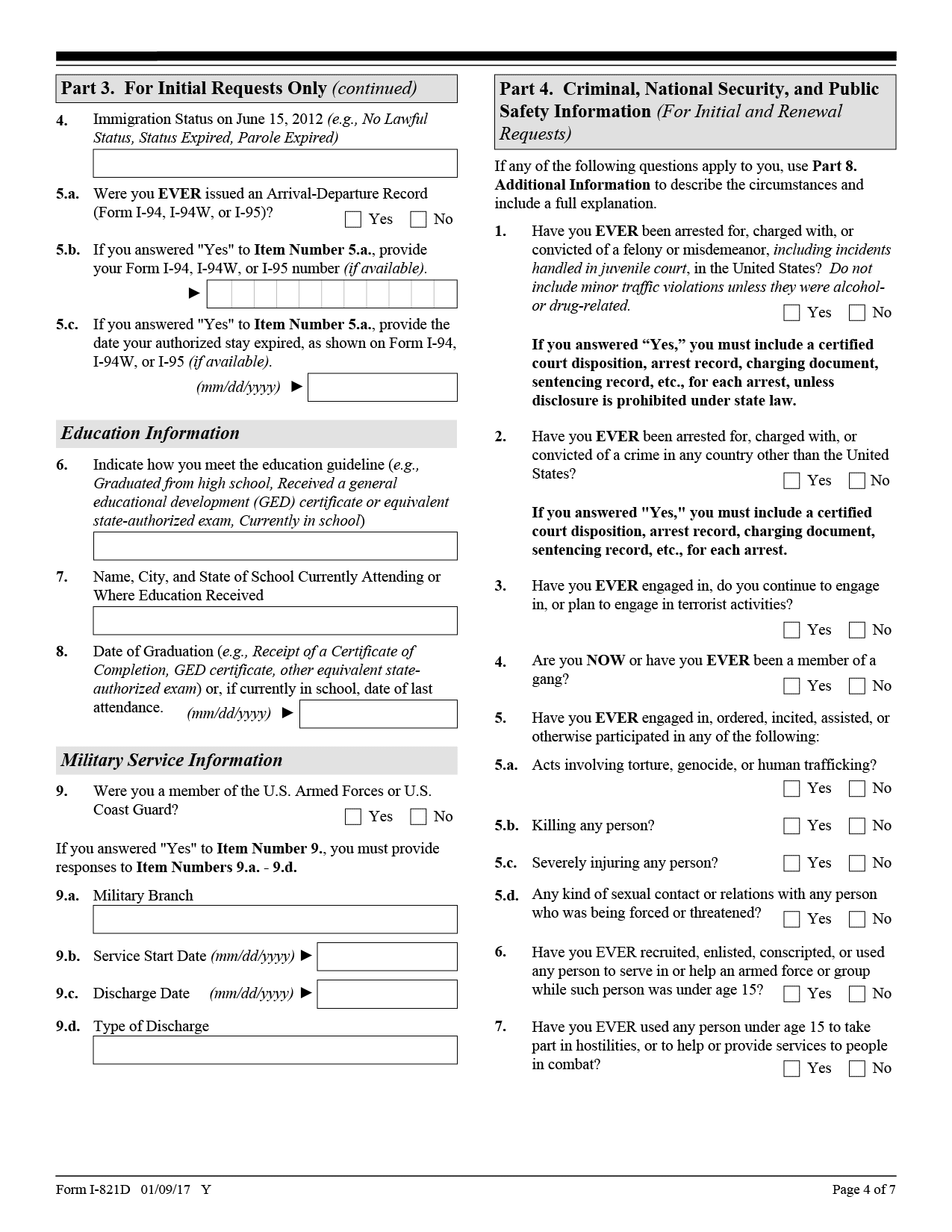

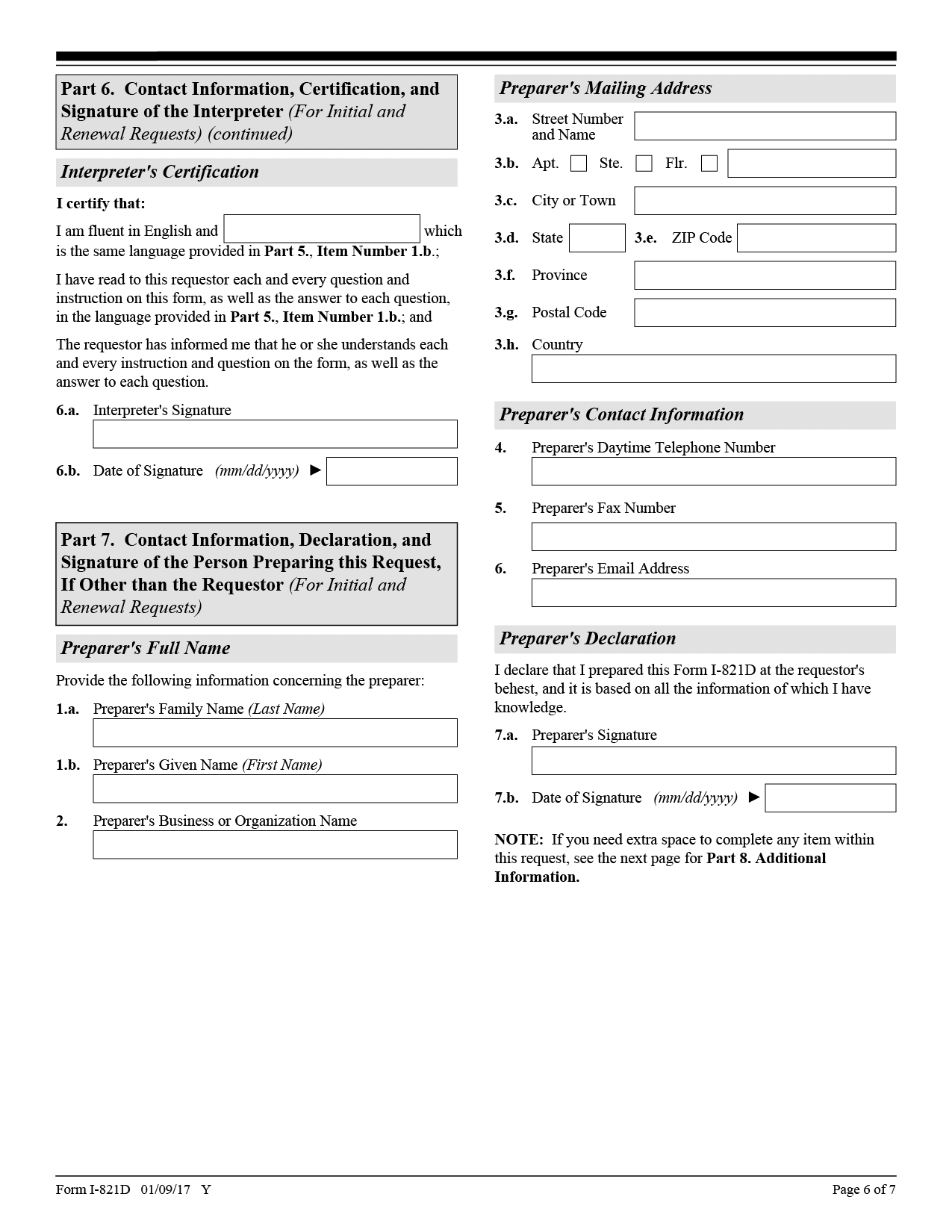

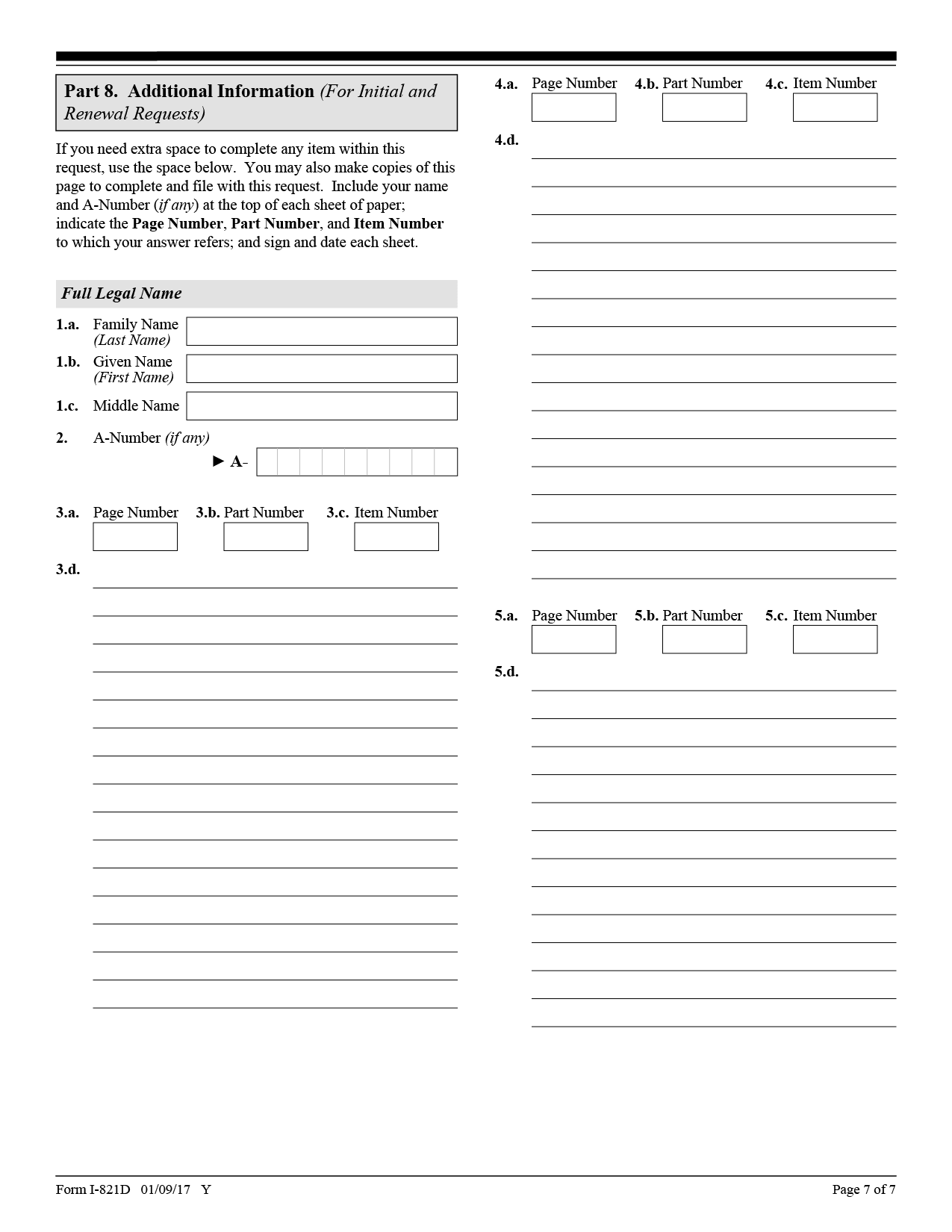

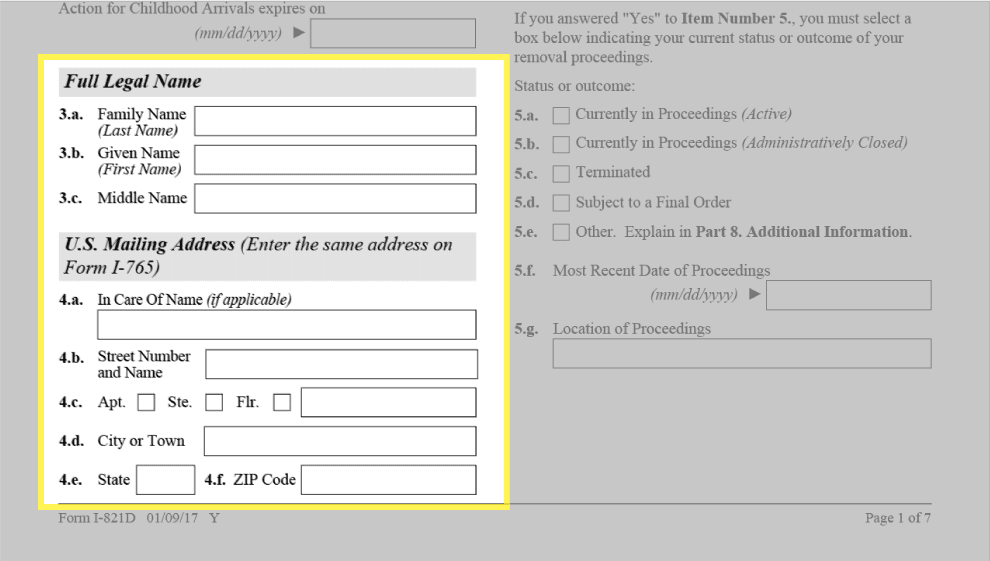

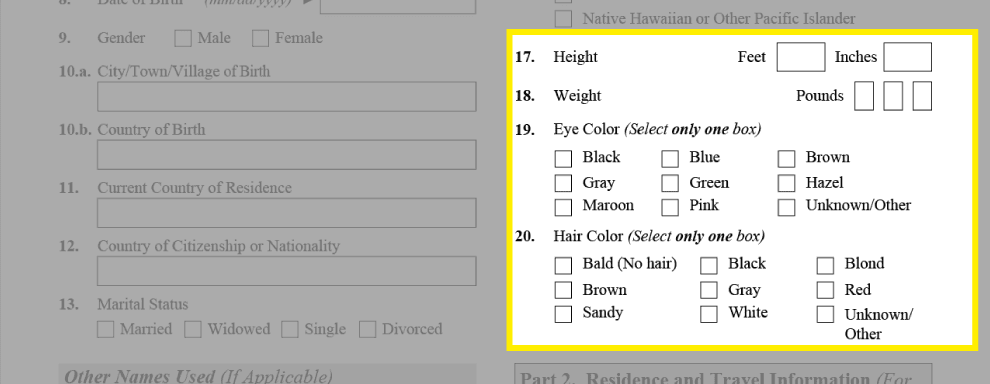

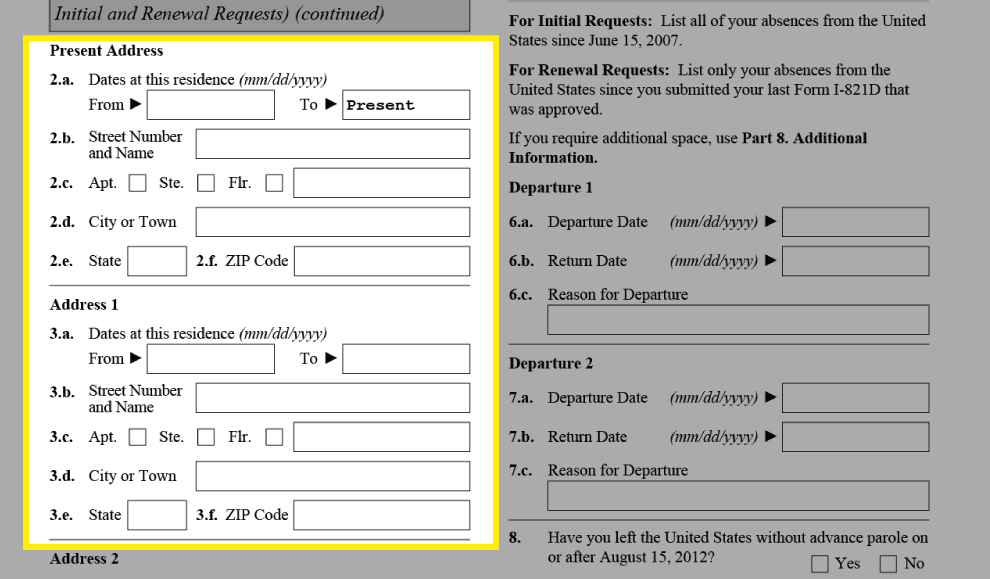

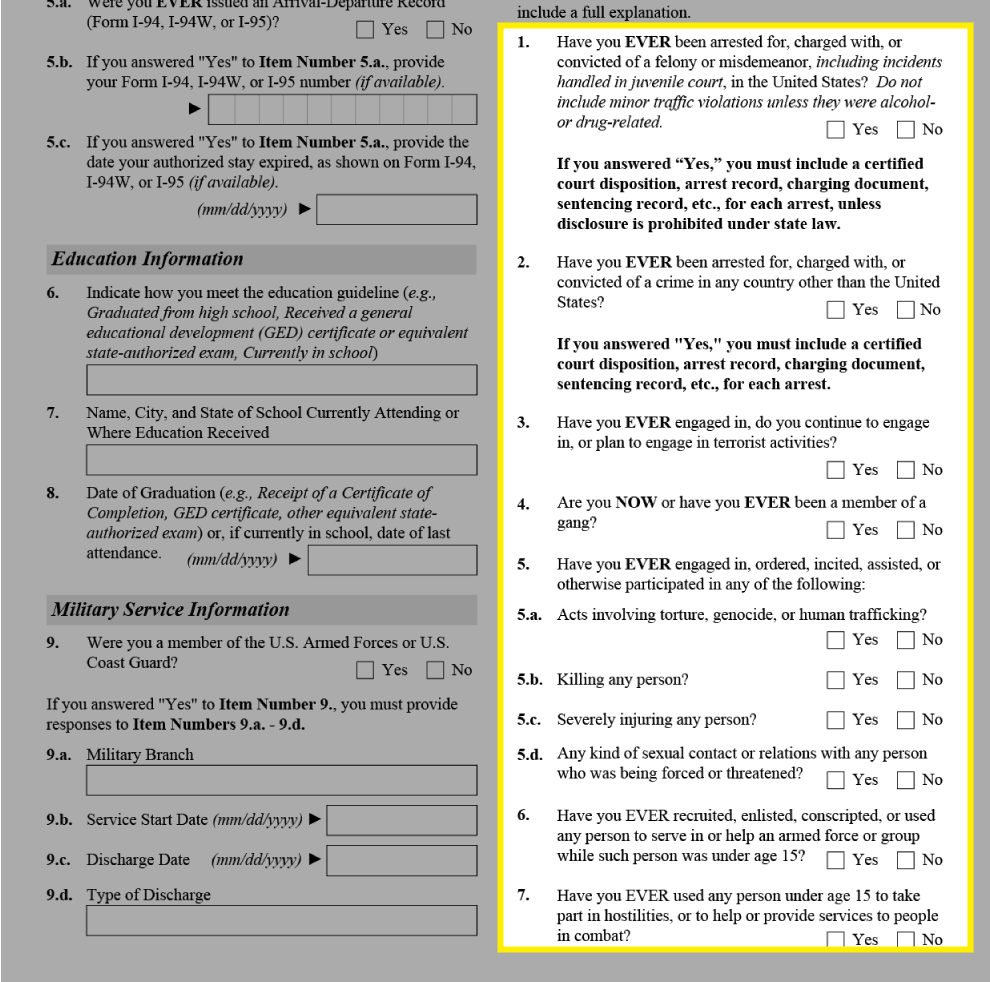

And advocates say the actual document DACA applicants have to fill out, known as Form I-821D, gives plenty of cause for concern.

The DACA database shows just how sophisticated the data collection around immigration has become — and what information authorities have access to as political tides turn.

“Agencies didn’t use to talk to each other. Back then you’d take a fingerprint on paper. Then 9/11 happened and people blamed immigrants and then they introduced mass data collection,” said Valdez.

And Anne Chandler, executive director of the Tahirih Justice Center’s Houston office, said she already believes DHS uses this information to “initiate deportations of individuals and their family members.” But, she added, “What I haven’t seen is a wide scale systematic approach of combing databases for mass deportations. […] I’m very concerned about that.”